I wrote recently about E.B. Ford, 'the Kenneth Williams of Zoology', the decidedly eccentric author of Butterflies, the first in the classic New Naturalist series. Browsing in The Aurelian Legacy (a book I have surely mentioned before), I came across another anecdote about 'Henry', as he was called in ironic reference to his deep distaste for the modern world. Among the things he disapproved of were the radio, newspapers and fish-and-chips, and for him it was invariably a 'photographic camera' and a 'cinematic projector', while any complex piece of machinery required for the laboratory was 'the engine'. But to the anecdote.

Miriam Rothschild, the great entomologist who became one of the few women Ford was prepared to regard as a thinking organism, first came across 'Henry' in the Zoology Department at Oxford. Meaning to introduce herself, she knocked on the door of his office and waited..

'After a moment's silence there was a rather plaintive long drawn out cry: "Come in!" I opened the door and found an empty room. I looked round nervously - not a soul to be seen, but an almost frightening neatness pervaded everything. Each single object, from paper knife to Medical Genetics was in its right place. Each curtain hung in a predestined fold... the sight of this distilled essence of neatness and order took my breath away. I stood there, probably with my mouth open, trying to reconcile this vacant room with that ghostly cry - had I dreamed it? - when suddenly Professor Ford appeared from underneath his desk like a graceful fakir emerging from a grave. Apparently he had been sitting crosslegged on the floor in the well of his writing table, lost in thought, but he held out his hand to me in a most affable manner... "My dear Mrs Lane [her married name] - I didn't know it was you."' Miriam Rothschild concluded 'you never have to ask a great man for an explanation.'

Not E.B. Ford anyway.

Sunday, 31 August 2014

Friday, 29 August 2014

And a Moth

I spent some while last night trying to identify a moth - a fool's errand, of course.

The moth had settled on the bathroom wall, and what piqued my interest was that its wings were held in a decidedly butterfly-like pose, half-way between flat and folded, much like a Blue butterfly - and indeed, in size it was on just that scale. The colour, however, could hardly have been less blue: a wheaten ground, with three wavy brown bars across the forewings, two very thin and one thicker and darker. What, I wondered, could it be? Foolishly I thought the butterfly-like pose might narrow down the field - not by much, I discovered, and, after a fruitless on-line search, I was soon forlornly rifling through my ancient, but notably compendious and well illustrated, book of British butterflies and moths, written by W.E. Kirby around a century ago. In the end, I had it narrowed down to some kind of Thorn moth - indeed, with its small size, it really should have been the Little Thorn (Cepphis advenaria) - but that one, I discovered, flies in May and June (and the August Thorn is too large).

That's the trouble with moths - there are just too many of them. Whereas we British butterfly fanciers have barely 60 species to identify - in practice far fewer, unless we're making a point of travelling around the country ticking them all off the list - moth species add up to a daunting 2,400-plus, of which more than 800 are macro-lepidoptera (i.e. easily visible). The genus that includes the Thorns (Ennominae) alone includes more than 80 British species. Moths are undeniably beautiful, often in a subtle and understated way (as with my Thorny enigma), but really it is far easier just to say 'Oh - a moth', to look and enjoy, than it is to identify the little beauties (there are several species of Beauty moth in the genus Ennominae).

As for the stranger on my bathroom wall, when I last saw it, it was resting in a much more moth-like pose, its banded wings spread flat. And this morning it was gone.

The moth had settled on the bathroom wall, and what piqued my interest was that its wings were held in a decidedly butterfly-like pose, half-way between flat and folded, much like a Blue butterfly - and indeed, in size it was on just that scale. The colour, however, could hardly have been less blue: a wheaten ground, with three wavy brown bars across the forewings, two very thin and one thicker and darker. What, I wondered, could it be? Foolishly I thought the butterfly-like pose might narrow down the field - not by much, I discovered, and, after a fruitless on-line search, I was soon forlornly rifling through my ancient, but notably compendious and well illustrated, book of British butterflies and moths, written by W.E. Kirby around a century ago. In the end, I had it narrowed down to some kind of Thorn moth - indeed, with its small size, it really should have been the Little Thorn (Cepphis advenaria) - but that one, I discovered, flies in May and June (and the August Thorn is too large).

That's the trouble with moths - there are just too many of them. Whereas we British butterfly fanciers have barely 60 species to identify - in practice far fewer, unless we're making a point of travelling around the country ticking them all off the list - moth species add up to a daunting 2,400-plus, of which more than 800 are macro-lepidoptera (i.e. easily visible). The genus that includes the Thorns (Ennominae) alone includes more than 80 British species. Moths are undeniably beautiful, often in a subtle and understated way (as with my Thorny enigma), but really it is far easier just to say 'Oh - a moth', to look and enjoy, than it is to identify the little beauties (there are several species of Beauty moth in the genus Ennominae).

As for the stranger on my bathroom wall, when I last saw it, it was resting in a much more moth-like pose, its banded wings spread flat. And this morning it was gone.

Thursday, 28 August 2014

Birthday Betjeman

Born on this day in 1906 was John Betjeman, 'poet and hack' as he described himself in Who's Who. He was, of course, much more than that, but he was a rare example of a literary (if often low-brow) poet who was hugely popular and well-loved, a 'national treasure' and a celebrity. His penchant for jogalong metre kept him firmly in the light verse tradition, but there is often in his works an interesting counterpoint between the jaunty rhythm on the surface and a strong undertow of melancholy below. Here is a curiosity, taken from a Michael Parkinson chat show (Betjeman was a great talk-show favourite), in which the late Kenneth Williams and Maggie Smith (now enjoying a late flowering as Lady Violet, the only character in Downton with any lines) reading Betjeman's early Death in Leamington, to the apparent delight of the author.

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

'A permanent trail of imagination...'

Exciting news here for us retroprogressives, as the clacking of manual typewriters is heard again in the newsroom of The Times (where, sadly, it seems to be causing more bemusement than anything). I guess there must be many working in newspapers now who have never heard the sound, let alone used a manual typewriter - and if they did, they'd probably wonder how anyone ever managed to bash out a story with such a cumbersome machine. But for some, the manual typewriter still has a certain inky allure - not least Tom Hanks, who has even developed an app that gives the illusion of writing with an old-fashioned typewriter. Typing with a manual, he says, 'stamps into paper a permanent trail of imagination through keys, hammers, cloth and dye' - an eloquent expression of what is special about manual typing. It is closer to a craft process than the frictionless, resistance-free electronic transaction that is 'typing' with a modern computer keyboard - writing in cyberspace rather than on paper.

It is surely true that the sheer cumbersomeness of manual typing and the difficulty of rewriting encouraged forethought, care and brevity, whereas the ease of the modern keyboard encourages the reverse - get it all down any old how, knock it into shape afterwards, and if it's too long, well, it's too long. The endless stories on the BBC News website (and many others) are classic products of keyboard writing - as, I suspect, are many overlong works of contemporary fiction. The modern keyboard has made writing too easy.

It is surely true that the sheer cumbersomeness of manual typing and the difficulty of rewriting encouraged forethought, care and brevity, whereas the ease of the modern keyboard encourages the reverse - get it all down any old how, knock it into shape afterwards, and if it's too long, well, it's too long. The endless stories on the BBC News website (and many others) are classic products of keyboard writing - as, I suspect, are many overlong works of contemporary fiction. The modern keyboard has made writing too easy.

Monday, 25 August 2014

Sign of the Times?

Talking of the Today programme, as we were the other day (and so often before - truly it 'sets the agenda for the day', alas), I noted recently that John Humphrys, while interviewing some big wheel in the warmist world, mentioned the inconvenient truth that 'global warming' has barely happened over the past 15 years or so. I wondered if this might be a sign that the times are changing, that even the BBC might now be open to a degree of scepticism that would have been condemned as heretical just a couple of years ago. Well, the other day I happened on this story on the BBC News website, which looks like a hopeful sign - up to a point. The 'pause' story is never presented in terms of 'Whoops, looks like we were wrong' but only as a case of certain factors having been overlooked - and, in this case, the new prediction is that warming will be even worse when it does happen. In other words, we might have got it hopelessly wrong last time, but this time we're right, you'd better believe it, there can't possibly be any factors we're overlooking. Hmm...

More Butterflies

Bank Holiday Monday, and the rain is siling down in the time-honoured manner. However, the past couple of days had enough sunshine for a few late butterflies to venture out. On Saturday I was gifted with my first Small Copper of the year. I was skirting a golf course (averting my eyes), wading through the long dry grass beside the fairway, when suddenly, out of nowhere, it appeared - a bright, fresh and beautiful specimen. It perched on a flowerhead almost at my feet, flashed its wings a couple of times, and was off.

That was the only butterfly I saw that afternoon, but yesterday I headed for the Surrey Hills determined to see more. By the time I arrived at the hillside I was heading for, clouds had covered the sun, a wind had come up and my hopes were not high. However, as I explored, I soon came across a Chalkhill Blue - a tired and tatty female, but a joy to see, especially as it was my first of the year. Happily it was not to be the last. In the course of my wanderings, despite the unpromising conditions, I came across at least a dozen more, some fresh and vigorous, others looking decidedly end-of-season, but all of them beautiful in that unique silvery, cloudy, milky-blue Chalkhill way. And, by way of a bonus and to show just how intensely blue a blue can be, a male Adonis Blue flew past in all his shimmering glory. These were just the highlights; there were also Common blues galore, Small Heaths, Brown Argus... Even if it rains for the next month, that was a splendid climax to the butterfly year.

That was the only butterfly I saw that afternoon, but yesterday I headed for the Surrey Hills determined to see more. By the time I arrived at the hillside I was heading for, clouds had covered the sun, a wind had come up and my hopes were not high. However, as I explored, I soon came across a Chalkhill Blue - a tired and tatty female, but a joy to see, especially as it was my first of the year. Happily it was not to be the last. In the course of my wanderings, despite the unpromising conditions, I came across at least a dozen more, some fresh and vigorous, others looking decidedly end-of-season, but all of them beautiful in that unique silvery, cloudy, milky-blue Chalkhill way. And, by way of a bonus and to show just how intensely blue a blue can be, a male Adonis Blue flew past in all his shimmering glory. These were just the highlights; there were also Common blues galore, Small Heaths, Brown Argus... Even if it rains for the next month, that was a splendid climax to the butterfly year.

Friday, 22 August 2014

You read it here first

Those whose business involves making statements that are effectively meaningless but must appear to be full of pith and moment are always in need of new turns of phrase to make their airy nothings sound important. For some while, the phrase 'going forward' has been much employed, but lately it seems to have fallen out of use, having perhaps been too often lampooned. Time for a new form of words - and this morning I caught one that I think might well catch on. It was, of course, on the Today programme. I can't remember what the subject was, but a representative of HM Government found himself approving (or obliged to pretend he approved) of something his interlocutor had been doing. 'That,' he declared, 'is exactly the journey of travel the Government has been on.'Yes, journey of travel...

I think we are all, in a very real sense, on a journey of travel, are we not? Going forward.

I think we are all, in a very real sense, on a journey of travel, are we not? Going forward.

Thursday, 21 August 2014

The Awakening and a Hedgehog

This week Radio 4 is running a dramatisation of Kate Chopin's once-scandalous novel The Awakening as its 15 Minute Drama. Someone has had the bright idea of framing the action by having it observed through the eyes of a black maidservant, who provides a running commentary in the kind of caricatured, eye-rolling style you might have thought would be frowned on in these PC times. However, as the white characters too lay on the stage Southern accents and intonations with a trowel, it doesn't seem entirely out of place. What it does do, though, is fatally distance the action of what is on the page an intense and challenging read - just the kind of novel that would benefit from the intimacy that radio can achieve. Unless things pick up in the last couple of episodes, this looks like a sad misfire.

And in other news... This morning, on the way to the station, I saw a hedgehog. Sadly it was a two-dimensional hedgehog, having been flattened by a passing car, but I was still glad to see it, as it was the first evidence I'd seen of a hedgehog presence in the area for a decade or more. When I was a boy, hedgehogs came as standard with every suburban garden, and they thrived in town (well, suburb) and country alike - but by the late Nineties, seeing one was becoming a bit of an event. And then there were none - or so it seemed. It's good to know they're still around after all, and I hope the next one I see is alive and well and taking care when crossing the road.

And in other news... This morning, on the way to the station, I saw a hedgehog. Sadly it was a two-dimensional hedgehog, having been flattened by a passing car, but I was still glad to see it, as it was the first evidence I'd seen of a hedgehog presence in the area for a decade or more. When I was a boy, hedgehogs came as standard with every suburban garden, and they thrived in town (well, suburb) and country alike - but by the late Nineties, seeing one was becoming a bit of an event. And then there were none - or so it seemed. It's good to know they're still around after all, and I hope the next one I see is alive and well and taking care when crossing the road.

Wednesday, 20 August 2014

'Don't read much now...'

Among the clips of Philip Larkin in Great Poets in Their Own Words was one of the poet reading (in that decidedly posh voice of his) A Study of Reading Habits -

When getting my nose in a book

Cured most things short of school,

It was worth ruining my eyes

To know I could still keep cool,

And deal out the old right hook

To dirty dogs twice my size.

Later, with inch-thick specs,

Evil was just my lark:

Me and my coat and fangs

Had ripping times in the dark.

The women I clubbed with sex!

I broke them up like meringues.

Don't read much now: the dude

Who lets the girl down before

The hero arrives, the chap

Who's yellow and keeps the store

Seem far too familiar. Get stewed:

Books are a load of crap.

This is Larkin in one of his blokey personas (as in Self's the Man and, in extreme form, This Be the Verse), moving from an account of childhood reading that is plausibly autobiographical to a middle stanza that hints at darker things (and contains what is surely the only known use of the rhyme 'fangs' and 'meringues') before the shadows close in for the final, terminally disenchanted stanza, to arrive at that bleak, and clearly far from autobiographical, conclusion. As ever with Larkin, the rigorous formal control of this awkward, unsettling material is masterly.

Larkin completed and dated A Study of Reading Habits on this day in 1960.

When getting my nose in a book

Cured most things short of school,

It was worth ruining my eyes

To know I could still keep cool,

And deal out the old right hook

To dirty dogs twice my size.

Later, with inch-thick specs,

Evil was just my lark:

Me and my coat and fangs

Had ripping times in the dark.

The women I clubbed with sex!

I broke them up like meringues.

Don't read much now: the dude

Who lets the girl down before

The hero arrives, the chap

Who's yellow and keeps the store

Seem far too familiar. Get stewed:

Books are a load of crap.

This is Larkin in one of his blokey personas (as in Self's the Man and, in extreme form, This Be the Verse), moving from an account of childhood reading that is plausibly autobiographical to a middle stanza that hints at darker things (and contains what is surely the only known use of the rhyme 'fangs' and 'meringues') before the shadows close in for the final, terminally disenchanted stanza, to arrive at that bleak, and clearly far from autobiographical, conclusion. As ever with Larkin, the rigorous formal control of this awkward, unsettling material is masterly.

Larkin completed and dated A Study of Reading Habits on this day in 1960.

Tuesday, 19 August 2014

Maybe this time...

Regular readers will know of my penchant for that most elegant form of gentleman's neckwear, the cravat (search 'cravat' on this blog and you'll see what I mean). For some while I've been forlornly trying to spark a cravat revival, and kidding myself at intervals that it is finally under way. Well, now the revival has the force of the mighty BBC News website behind it, to say nothing of light entertainment legend Nicholas Parsons. Yes indeed - 'the world's first Nicholas Parsons-driven fashion revolution is surely under way'. Let's hope so...

Graham Robb's Ancient Paths

I've been reading The Ancient Paths by Graham Robb, whose recent history The Discovery of France was such an eye-opener. The Ancient Paths - subtitled Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe - is, in its very different way, quite an eye-opener too. It's a book Robb really didn't want to write. 'The idea that became this book,' he writes, 'arrived one evening like an unwanted visitor. It clearly expected to stay a long time, and I knew that its presence in my house would be extremely compromising. Treasure maps and secret paths belong to childhood. An adult scholar who sees an undiscovered ancient world reveal itself, complete with charts, instruction manual and guidebook, is bound to question the functioning of his mental equipment.' That idea was so startling that Robb spent several years trying to disprove it, convinced that it couldn't possibly be right and that this kind of thing was the proper preserve of cranks and obsessives. But the more he looked, the more he saw to confirm and fill out his original idea...

What's it about? In a nutshell, Robb argues - in depth and detail and with a wealth of corrroborative evidence - that Druids (yes, Druids) used their knowledge of Pythagorean geometry and the movements of the Sun to survey and map their world with extraordinary precision, enabling rapid and effective communication and transport across it. These Druids were not white-robed mystics but a highly educated and civilised elite, the products of a 20-year education, Greek speakers who mingled on more or less equal terms with the highest in Roman society. They - along with virtually all the more attractive and civilised features of the Celtic world - were erased from the record by the conquering Romans, who were at pains to portray their enemies as mere painted savages, and to destroy the more impressive evidence to the contrary.

As I say, Robb lays out his case in great detail, with maps and diagrams galore, and long lists of place names (skipping is an option). I'm no expert, but it all seems pretty persuasive to me, and makes quite fascinating reading - if true, it really is quite revolutionary... If nothing else, Robb's findings support the very sound thesis that Everything is much older than we think, and much more complex. Thanks to the myth of Progress, combined with the fact that history is written by the victors and that so little material evidence survives from most eras, we tend to look back into the past as into an ever thickening darkness, in which the botched prototypes of the Enlightened Man to come grope and stumble about in benighted ignorance. It was never so.

What's it about? In a nutshell, Robb argues - in depth and detail and with a wealth of corrroborative evidence - that Druids (yes, Druids) used their knowledge of Pythagorean geometry and the movements of the Sun to survey and map their world with extraordinary precision, enabling rapid and effective communication and transport across it. These Druids were not white-robed mystics but a highly educated and civilised elite, the products of a 20-year education, Greek speakers who mingled on more or less equal terms with the highest in Roman society. They - along with virtually all the more attractive and civilised features of the Celtic world - were erased from the record by the conquering Romans, who were at pains to portray their enemies as mere painted savages, and to destroy the more impressive evidence to the contrary.

As I say, Robb lays out his case in great detail, with maps and diagrams galore, and long lists of place names (skipping is an option). I'm no expert, but it all seems pretty persuasive to me, and makes quite fascinating reading - if true, it really is quite revolutionary... If nothing else, Robb's findings support the very sound thesis that Everything is much older than we think, and much more complex. Thanks to the myth of Progress, combined with the fact that history is written by the victors and that so little material evidence survives from most eras, we tend to look back into the past as into an ever thickening darkness, in which the botched prototypes of the Enlightened Man to come grope and stumble about in benighted ignorance. It was never so.

Monday, 18 August 2014

Poets on TV

Last night on BBC4 I caught the second of two programmes titled Great Poets in Their Own Words. I'd missed the first, and this was the one covering the latter half of the 20th century. Essentially it was a compilation of archive clips featuring poets talking about their work. The Great in the title was perhaps redundant, as the nearest this got to greatness was Larkin (followed, a long way behind, by Heaney and Hughes?) Naturally an archive show like this is bound to favour the more flatulent and self-publicising among the poetic community - cue much footage of Ginsberg and co, a very drunk Berryman, the Liverpool Poets, Linton Kwesi Johnson... No Geoffrey Hill here, nor Richard Wilbur (I'm assuming Auden was dealt with in the first programme) - and a bit of Stevie Smith footage would have been welcome. Hughes and Plath featured quite large, despite a notable shortage of material (Plath never appeared on TV).

But there was Larkin - who, for all his 'hermit of Hull' reputation, seems to have been on TV rather a lot, most notably in a BBC Monitor documentary, in which he was interviewd by John Betjeman (JB's only appearance, despite the masses of archive he left behind). It's strange and rather unsettling to see Larkin enacting his great poem Church Going for the cameras, and loping myopically about his workplace - what scabrous commentary was going through his head, I wonder, as he performed Philip Larkin, Poet and Librarian? It's probably as well we don't know...

But there was Larkin - who, for all his 'hermit of Hull' reputation, seems to have been on TV rather a lot, most notably in a BBC Monitor documentary, in which he was interviewd by John Betjeman (JB's only appearance, despite the masses of archive he left behind). It's strange and rather unsettling to see Larkin enacting his great poem Church Going for the cameras, and loping myopically about his workplace - what scabrous commentary was going through his head, I wonder, as he performed Philip Larkin, Poet and Librarian? It's probably as well we don't know...

Friday, 15 August 2014

Critical Thinking Nosedives

I see record numbers of young people are heading for university following yesterday's announcement of A-Level results, even though they showed an infinitesimal 'dip' in grades. Advanced Level is an exam with a 98 percent pass rate - a sad index of its intellectual rigour - and with top grades awarded to more than a quarter of entrants. Still - good luck to those who have chosen to go on to university, and let's hope they're doing the right thing for them.

What struck me about the breakdown of these A-Level results was that one subject was now being taken by a startling 46 percent fewer pupils year on year - a uniquely steep, probably terminal decline. And it was not, alas, Media Studies or even General Studies - it was Critical Thinking. I must admit I did not know such an A-Level subject existed - but as it does, it should surely be regarded by the universities as a serious core subject. If a university education teaches one thing, that thing should be Critical Thinking. No doubt, as taught to A-Level, it is a fuzzy option that universities are right not to take seriously - but there's no reason why it should be. Rather, it should be stiffened up and put right at the core of any education, especially at university level. Heaven knows we could do with a lot more critical thinking - not least among the products of our universities.

What struck me about the breakdown of these A-Level results was that one subject was now being taken by a startling 46 percent fewer pupils year on year - a uniquely steep, probably terminal decline. And it was not, alas, Media Studies or even General Studies - it was Critical Thinking. I must admit I did not know such an A-Level subject existed - but as it does, it should surely be regarded by the universities as a serious core subject. If a university education teaches one thing, that thing should be Critical Thinking. No doubt, as taught to A-Level, it is a fuzzy option that universities are right not to take seriously - but there's no reason why it should be. Rather, it should be stiffened up and put right at the core of any education, especially at university level. Heaven knows we could do with a lot more critical thinking - not least among the products of our universities.

Thursday, 14 August 2014

Icons

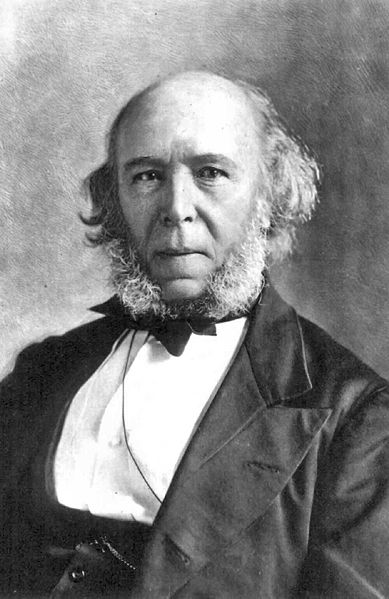

I was looking at the portrait of Charles Darwin on a £10 note just now when a little thought experiment occurred to me... There was Darwin, the very image of a big-brained, bearded, wise old ape, brooding on his huge and discomfiting Idea. Evolution could have no better icon. But suppose, I wondered, suppose Darwin looked like Herbert Spencer (above). The Idea, of course, would still be there - but its iconic force would surely be much diminished.

Similarly, suppose Einstein had not looked like everyone's idea of the mega-brained, wild-haired professor, his head bursting with world-shattering ideas and profound insights? Suppose he had looked more like, say, Niels Bohr, who could have passed for a bank manager...

Or suppose Stephen Hawking, instead of being the very image of a mighty mind trapped in a useless body, had been able-bodied? Hard to believe he'd have been quite the world-conquering celeb he is today...

At least Richard Dawkins, for all his fame, is unlikely to become an Icon, blesses as he is with the bland, polished features of an Anglican bishop - albeit one who looks after himself and has a good barber.

Similarly, suppose Einstein had not looked like everyone's idea of the mega-brained, wild-haired professor, his head bursting with world-shattering ideas and profound insights? Suppose he had looked more like, say, Niels Bohr, who could have passed for a bank manager...

Or suppose Stephen Hawking, instead of being the very image of a mighty mind trapped in a useless body, had been able-bodied? Hard to believe he'd have been quite the world-conquering celeb he is today...

At least Richard Dawkins, for all his fame, is unlikely to become an Icon, blesses as he is with the bland, polished features of an Anglican bishop - albeit one who looks after himself and has a good barber.

Wednesday, 13 August 2014

Lager

I must admit I like a good lager - chiefly because I find it the most effective instant pick-me-up (and thirst quencher) after a day's exertions. Note, I say a 'good lager', and I am quite sure that there is such a thing, that it tastes better, and that I could tell the difference blindfold. I was therefore rather startled to come across this report, which concludes that all lagers taste the same.

I wonder what they were actually tasting - draught, bottled, canned? Bottled Budvar is surely distinctive enough to be told from the other two, though there may be some denatured draught version that tastes much the same, as draught lagers tend to (though even the widely available Kronenbourg certainly tastes different from Stella and Heineken). The main distinction in lagers is - to my palate at least - between the generic, brewed anywhere, Europop style, which, particularly in England, has a nasty sour-stale overtone, and those lagers that are still custom-brewed. This is illustrated perfectly by canned Heineken: the version that is still brewed in Holland is about the best lager you can get in a can, whereas the Europop ('brewed in the EU') version is really quite nasty. Both kinds are now on sale in the UK, but happily the good ones still bear the legend 'Brewed in Holland'. But I have detained you long enough...

I wonder what they were actually tasting - draught, bottled, canned? Bottled Budvar is surely distinctive enough to be told from the other two, though there may be some denatured draught version that tastes much the same, as draught lagers tend to (though even the widely available Kronenbourg certainly tastes different from Stella and Heineken). The main distinction in lagers is - to my palate at least - between the generic, brewed anywhere, Europop style, which, particularly in England, has a nasty sour-stale overtone, and those lagers that are still custom-brewed. This is illustrated perfectly by canned Heineken: the version that is still brewed in Holland is about the best lager you can get in a can, whereas the Europop ('brewed in the EU') version is really quite nasty. Both kinds are now on sale in the UK, but happily the good ones still bear the legend 'Brewed in Holland'. But I have detained you long enough...

Tuesday, 12 August 2014

Justice

Donald Justice would be 89 today, if he were still with us. His quiet voice lives on and strengthens with the years, while more strident and self-advertising poets of similar vintage seem headed, ultimately, for oblivion. What better way to celebrate Justice's birthday than with a poem? This one is from his second collection, Night Light - a collection, as one review noted, 'suffused with elegiac, elegant grief'. Indeed it is...

Bus Stop

Lights are burning

In quiet rooms

Where lives go on

Resembling ours.

The quiet lives

That follow us—

These lives we lead

But do not own—

Stand in the rain

So quietly

When we are gone,

So quietly . . .

And the last bus

Comes letting dark

Umbrellas out—

Black flowers, black flowers.

And lives go on.

And lives go on

Like sudden lights

At street corners

Or like the lights

In quiet rooms

Left on for hours,

Burning, burning.

Monday, 11 August 2014

Swifts

I thought they had all gone - departed early and abruptly, the unwontedly fine English summer having given them all they required. The last excited flypasts I saw were in the final days of July, and since then I have only spotted a few stragglers, the last of them - or so I thought - last Wednesday. But yesterday evening, at the end of a day of alternating sunshine and stormy downpours, I happened to glance out of the front-room window - and there was that familiar sickle shape. I dashed out of the front door and, yes, there it was - in the now clear blue sky, a solitary swift, circling quite low and leisurely, as if returning to take a last look round old haunts. I followed its flight over the back garden, then back to the road, before eventually it sailed off elsewhere, perhaps to begin the great journey South.

Edward Thomas seemed always to know when he had seen his last swift:

How at once should I know,

When stretched in the harvest blue

I saw the swift's black bow,

That I would not have that view

Another day

Until next May

Again it is due?

The same year after year -

But with the swift alone.

With other things I but fear

That they will be over and done

Suddenly

And I only see

Them to know them gone.

I'm not sure yesterday's swift was my last of the year, but if it was, it was a perfect, heart-lifting end to the swift summer.

Edward Thomas seemed always to know when he had seen his last swift:

How at once should I know,

When stretched in the harvest blue

I saw the swift's black bow,

That I would not have that view

Another day

Until next May

Again it is due?

The same year after year -

But with the swift alone.

With other things I but fear

That they will be over and done

Suddenly

And I only see

Them to know them gone.

I'm not sure yesterday's swift was my last of the year, but if it was, it was a perfect, heart-lifting end to the swift summer.

Sunday, 10 August 2014

It Was a Gas

I see that Nitrous Oxide - 'laughing gas' - is in fashion again, just as it was back in the 1790s, though it was then enjoyed by a rather more select band of enthusiasts.

At the Pneumatic Institute, the brainchild of Dr Thomas Beddoes (father of that strange poet Thomas Lovell Beddoes), in Bristol, the young scientific whiz kid Humphry Davy was throwing himself into the grand project of experimenting with Nitrous Oxide. The hope was that it would have near-miraculous therapeutic properties - and who knew what other uses - and Davy was keen to experiment on himself (as he had already done with Carbon Monoxide, with very nearly fatal results) to find out its effects.

After inhaling four quarts, Davy noted 'highly pleasurable thrilling, particularly in the chest and extremities. The objects around me became dazzling, and my hearing more acute... Sometimes I manifested my pleasure by stamping or laughing only; at other times, by dancing around the room and vociferating... This gas raised my pulse upwards of twenty strokes, made me dance about the laboratory as a madman, and has kept my spirits in a glow ever since.'

No wonder he was keen to press on. 'Between April and June I constantly breathed the gas sometimes three or four times a day for a week... I have often felt very great pleasure when breathing it alone, in darkness and silence, occupied only by ideal existence.' What, he wondered, would be the effect of an overdose? After inhaling a full six quarts, he noted that 'the pleasurable sensation was at first local, and perceived in the lips and the cheeks. It gradually, however, diffused itself over the whole body, and in the middle of the experiment was for a moment so intense and pure as to absorb existence. At this moment, and not before, I lost consciousness; it was, however, quickly restored, and I endeavoured to make a bystander acquainted with the pleasures I experienced by laughing and stamping. I had no vivid ideas.'

Pressing on, he was soon making use of a portable gas chamber designed by James Watt, which enabled him to inhale eight quarts over a planned 75 minutes before being released from the chamber (with his pulse at 124, his temperature 106 and his face bright purple) and given a top-up of 20 quarts of pure gas. 'The sensations were superior to any I ever experienced. Inconceivably pleasurable,' he noted. 'Theories passed rapidly thro the mind, believed I may say intensely, at the same time that everything going on in the room was perceived. I seemed to be a sublime being, newly created and superior to other mortals, I was indignant at what they said of me and stalked majestically out of the laboratory to inform Dr Kinglake privately that nothing existed but thoughts.'

After some more experiments testing the effects of combining alcohol with nitrous oxide - it seems it's good for hangovers - Davy ended this self-experimenting phase, happily unscathed and with his mind sharper than ever.

The Pneumatic Institute was popular also with artists and writers, and Coleridge was among those sampling the laughing gas, noting 'an highly pleasurable sensation of warmth over my whole frame, resembling what I remember once to have experienced after returning from a walk in the snow into a warm room'. But he also felt, he wrote, 'more unmingled pleasure than I had ever before experienced'.

Robert Southey, who was to develop into a sedate and respectable Poet Laureate, was quite esctatic in his reactions to the gas, writing to his brother Tom: 'O, Tom! Such a gas has Davy discovered, the gaseous oxide. Oh, Tom! I have had some; it made me laugh and tingle in every toe and finger-tip. Davy has actually invented a new pleasure, for which language has no name. Oh, Tom! I am going for more this evening! It makes one strong and happy! So gloriously happy!'

Surely science was never such fun again.

[For more on all this - among many other things - see Richard Holmes's marvellous The Age of Wonder.]

At the Pneumatic Institute, the brainchild of Dr Thomas Beddoes (father of that strange poet Thomas Lovell Beddoes), in Bristol, the young scientific whiz kid Humphry Davy was throwing himself into the grand project of experimenting with Nitrous Oxide. The hope was that it would have near-miraculous therapeutic properties - and who knew what other uses - and Davy was keen to experiment on himself (as he had already done with Carbon Monoxide, with very nearly fatal results) to find out its effects.

After inhaling four quarts, Davy noted 'highly pleasurable thrilling, particularly in the chest and extremities. The objects around me became dazzling, and my hearing more acute... Sometimes I manifested my pleasure by stamping or laughing only; at other times, by dancing around the room and vociferating... This gas raised my pulse upwards of twenty strokes, made me dance about the laboratory as a madman, and has kept my spirits in a glow ever since.'

No wonder he was keen to press on. 'Between April and June I constantly breathed the gas sometimes three or four times a day for a week... I have often felt very great pleasure when breathing it alone, in darkness and silence, occupied only by ideal existence.' What, he wondered, would be the effect of an overdose? After inhaling a full six quarts, he noted that 'the pleasurable sensation was at first local, and perceived in the lips and the cheeks. It gradually, however, diffused itself over the whole body, and in the middle of the experiment was for a moment so intense and pure as to absorb existence. At this moment, and not before, I lost consciousness; it was, however, quickly restored, and I endeavoured to make a bystander acquainted with the pleasures I experienced by laughing and stamping. I had no vivid ideas.'

Pressing on, he was soon making use of a portable gas chamber designed by James Watt, which enabled him to inhale eight quarts over a planned 75 minutes before being released from the chamber (with his pulse at 124, his temperature 106 and his face bright purple) and given a top-up of 20 quarts of pure gas. 'The sensations were superior to any I ever experienced. Inconceivably pleasurable,' he noted. 'Theories passed rapidly thro the mind, believed I may say intensely, at the same time that everything going on in the room was perceived. I seemed to be a sublime being, newly created and superior to other mortals, I was indignant at what they said of me and stalked majestically out of the laboratory to inform Dr Kinglake privately that nothing existed but thoughts.'

After some more experiments testing the effects of combining alcohol with nitrous oxide - it seems it's good for hangovers - Davy ended this self-experimenting phase, happily unscathed and with his mind sharper than ever.

The Pneumatic Institute was popular also with artists and writers, and Coleridge was among those sampling the laughing gas, noting 'an highly pleasurable sensation of warmth over my whole frame, resembling what I remember once to have experienced after returning from a walk in the snow into a warm room'. But he also felt, he wrote, 'more unmingled pleasure than I had ever before experienced'.

Robert Southey, who was to develop into a sedate and respectable Poet Laureate, was quite esctatic in his reactions to the gas, writing to his brother Tom: 'O, Tom! Such a gas has Davy discovered, the gaseous oxide. Oh, Tom! I have had some; it made me laugh and tingle in every toe and finger-tip. Davy has actually invented a new pleasure, for which language has no name. Oh, Tom! I am going for more this evening! It makes one strong and happy! So gloriously happy!'

Surely science was never such fun again.

[For more on all this - among many other things - see Richard Holmes's marvellous The Age of Wonder.]

Saturday, 9 August 2014

Kay Ryan: Doing it again

I've remarked before on Kay Ryan's extraordinary ability to condense a world of meaning - of truth indeed - into a few short, simple lines and images. Here she is, doing it again, in a poem I came across last night while browsing in The Best of It:

Learning

Whatever must be learned

is always at the bottom,

as with the law of drawers

and the necessary item.

It isn't pleasant,

whatever they tell children,

to turn out on the floor

the folded things in them.

What weight that word 'folded' (the only long 'o' sound in the poem) carries - and those 'folded things'...

Learning

Whatever must be learned

is always at the bottom,

as with the law of drawers

and the necessary item.

It isn't pleasant,

whatever they tell children,

to turn out on the floor

the folded things in them.

What weight that word 'folded' (the only long 'o' sound in the poem) carries - and those 'folded things'...

Thursday, 7 August 2014

Another Edward Thomas

From one of the many documentaries marking the centenary of the Kaiser War, I picked up the arresting fact that the man who fired the first British shot of that war shared his name with one of its greatest poets - Edward Thomas. Drummer (later Corporal) Edward Thomas of the 4th Dragoon Guards was on reconnaissance near the village of Casteau in Belgium, on August 22nd, 1914, when his troop came across four German cavalrymen. They chased them down and, in the ensuing confrontation, Thomas shot and wounded one of them. And that was it.

Thomas himself - the other Edward Thomas, that is - put his feelings about the war and his particular form of patriotism into an angry but wise poem written after a blazing row with his more conventionally patriotic father, on Boxing Day, 1915:

This is no case of petty right or wrong

That politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true: –

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.

Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate her foe.

Thomas himself - the other Edward Thomas, that is - put his feelings about the war and his particular form of patriotism into an angry but wise poem written after a blazing row with his more conventionally patriotic father, on Boxing Day, 1915:

This is no case of petty right or wrong

That politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true: –

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.

Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate her foe.

Wednesday, 6 August 2014

Cameron: Looking at Fish

Hats off to David Cameron? Well, kind of, provisionally, maybe lifted an inch or two from the pate... I find myself quite impressed by how, in the face of what the BBC describes as 'huge pressure' and amid much outcry in the media and among his fellow politicians (and even the resignation of the Tories' token Muslim Woman), Cameron has so far not joined in the hand-wringing, moral grandstanding and wholesale condemnation of Israel over what is going on in Gaza. No, rather than cave in to that 'huge pressure', he employs himself (so far anyway) doing what he loves to do - looking at fish in a fish market. He was doing it last year, he's doing it this year, he clearly intends to go on doing it every time he find himself anywhere near a fish market. Good for him! To paraphrase Dr Johnson, a man is seldom more innocently employed than when he is looking at fish. Especially a politician...

Tuesday, 5 August 2014

Monday, 4 August 2014

Missa Whaat?

Half-listening to the radio last night as I drifted towards sleep, I heard what I took to be a traditional setting of the Mass for four male voices - but there seemed to be something wrong with the words. What was it? I could only make out odd fragments, so was none the wiser, until the presenter (the Right Rev Mark Tully) came on and told us that it was... Missa Charles Darwin!

Yes, a bright spark called Gregory Brown had decided to put words from Darwin's seminal works and correspondence to a traditional Mass setting. You can read all about it here, and listen online if you care to... It put me in mind of those absurd Temples of Reason that sprang up after the French Revolution, appropriating the apparatus of Christianity and adapting its rituals to lend spurious resonance to atheism and humanism. A Mass based on Darwin's writings strikes me as either a fabulously stupid gesture or blasphemy, or perhaps both. No doubt some keen atheist is already at work on a Missa Richard Dawkins...

Yes, a bright spark called Gregory Brown had decided to put words from Darwin's seminal works and correspondence to a traditional Mass setting. You can read all about it here, and listen online if you care to... It put me in mind of those absurd Temples of Reason that sprang up after the French Revolution, appropriating the apparatus of Christianity and adapting its rituals to lend spurious resonance to atheism and humanism. A Mass based on Darwin's writings strikes me as either a fabulously stupid gesture or blasphemy, or perhaps both. No doubt some keen atheist is already at work on a Missa Richard Dawkins...

Sunday, 3 August 2014

Getting Round to Barbara Pym

I vaguely remember dipping into Barbara Pym back in the late Seventies, around the time her then neglected work was acclaimed by Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil in the TLS and her career was instantly revived. I was curious to see what all the fuss was about - and I could dimly discern it, but felt Pym's novels weren't really for me. This was probably because I was too young. Now that I am considerably more laden with years, I have finally got round to having a proper crack at Barbara Pym - and I have to report that Larkin and Cecil were bang on the money: she's brilliant.

This judgment is formed on the basis of just one novel (so far), but I can't remember when I last got so much sheer pleasure from a novel as I did from Jane And Prudence (published 1953). Through much of the book, there was barely a paragraph that didn't make me smile, outwardly or inwardly, or laugh out loud. Pym's eye for the ridiculous is unfailing and her prose is wondrously supple and nuanced. An extremely deft craftswoman, she does just what is needed and no more - enough to bring her characters alive, place them in their world, and set the plot spinning. Her eye is clear but never cruel, even though there is really rather little to commend any of the characters - especially the men, who are a sorry bunch.

The reader's sympathy is generally with Jane, an Oxford graduate who had thought of being an academic but married a nice, rather dull vicar. With her gracelessness, dreadful clothes - she dresses as if she's going out to feed the chickens - and habit of coming out with wildly inappropriate, if well-meaning, contributions to any conversation, she put me in mind of Miranda (Miranda Hart's comic alter ego, that is - not Shakespeare's Miranda). You can't help but like her, though you probably wouldn't want to meet her.

There is rather less to be said for her more glamorous friend Prudence, who was at the same Oxford college but is a decade or so younger and unmarried (at the age of 29, which seems dangerously close to old maidhood in 1953). She seems to spend her life in a state of romantic self-delusion, drifting from one unsuitable and/or uninterested man to the next. Her unerring instinct for these (steered by the well-meaning Jane) leads her inevitably to the supine, dangerously handsome widower Fabian Driver, the novel's best comic creation, who's at the centre of most of the funniest and most excruciating scenes.

Also at the centre of things, at all times, is food: the action takes place against a daily round of cooked breakfasts, three-course lunches, cooked dinners and bedtime drinks (Ovaltine!) - not to mention the morning and afternoon tea and biscuits (or cakes) that are the main focus of purposeful activity in the office where Prudence works (if that isn't too strong a word). Meat - still on the ration in 1953 - is a constant preoccupation, because 'The men must have their meat', although, as one character darkly hints (to Jane's bemused dismay), they only really want 'one thing'.

This endless round of meals and snacks - how come there was no 'obesity epidemic' in those days? (see also Bowen) - and the leisurely pace of working life are among many things that remind us of how hugely different the England of 60 years ago was from the rushed, food-foraging, TV dinner present. Another is the preoccupation with religious identity. This is a world in which everybody (apart from a few oddballs) is a church-goer, and questions of High and Low are very much alive. It is also a world in which people read poetry - Prudence will sit over lunch reading Coventry Patmore(!), and Jane is forever quoting, or at least thinking of, lines from the Metaphysical poets (her speciality). This poetical vein running through the novel gives it a very distinctive flavour and hints at unexpected depths...

I read Jane And Prudence in a Virago Modern Classics paperback adorned with a wildly inappropriate chicklit-style jacket and prefaced with a gushing introduction by Jilly Cooper. But the back of that garish jacket carries this endorsement by Anne Tyler: 'Barbara Pym is the rarest of treasures; she reminds us of the heartbreaking silliness of everyday life.' That, I think, is exactly right.

This judgment is formed on the basis of just one novel (so far), but I can't remember when I last got so much sheer pleasure from a novel as I did from Jane And Prudence (published 1953). Through much of the book, there was barely a paragraph that didn't make me smile, outwardly or inwardly, or laugh out loud. Pym's eye for the ridiculous is unfailing and her prose is wondrously supple and nuanced. An extremely deft craftswoman, she does just what is needed and no more - enough to bring her characters alive, place them in their world, and set the plot spinning. Her eye is clear but never cruel, even though there is really rather little to commend any of the characters - especially the men, who are a sorry bunch.

The reader's sympathy is generally with Jane, an Oxford graduate who had thought of being an academic but married a nice, rather dull vicar. With her gracelessness, dreadful clothes - she dresses as if she's going out to feed the chickens - and habit of coming out with wildly inappropriate, if well-meaning, contributions to any conversation, she put me in mind of Miranda (Miranda Hart's comic alter ego, that is - not Shakespeare's Miranda). You can't help but like her, though you probably wouldn't want to meet her.

There is rather less to be said for her more glamorous friend Prudence, who was at the same Oxford college but is a decade or so younger and unmarried (at the age of 29, which seems dangerously close to old maidhood in 1953). She seems to spend her life in a state of romantic self-delusion, drifting from one unsuitable and/or uninterested man to the next. Her unerring instinct for these (steered by the well-meaning Jane) leads her inevitably to the supine, dangerously handsome widower Fabian Driver, the novel's best comic creation, who's at the centre of most of the funniest and most excruciating scenes.

Also at the centre of things, at all times, is food: the action takes place against a daily round of cooked breakfasts, three-course lunches, cooked dinners and bedtime drinks (Ovaltine!) - not to mention the morning and afternoon tea and biscuits (or cakes) that are the main focus of purposeful activity in the office where Prudence works (if that isn't too strong a word). Meat - still on the ration in 1953 - is a constant preoccupation, because 'The men must have their meat', although, as one character darkly hints (to Jane's bemused dismay), they only really want 'one thing'.

This endless round of meals and snacks - how come there was no 'obesity epidemic' in those days? (see also Bowen) - and the leisurely pace of working life are among many things that remind us of how hugely different the England of 60 years ago was from the rushed, food-foraging, TV dinner present. Another is the preoccupation with religious identity. This is a world in which everybody (apart from a few oddballs) is a church-goer, and questions of High and Low are very much alive. It is also a world in which people read poetry - Prudence will sit over lunch reading Coventry Patmore(!), and Jane is forever quoting, or at least thinking of, lines from the Metaphysical poets (her speciality). This poetical vein running through the novel gives it a very distinctive flavour and hints at unexpected depths...

I read Jane And Prudence in a Virago Modern Classics paperback adorned with a wildly inappropriate chicklit-style jacket and prefaced with a gushing introduction by Jilly Cooper. But the back of that garish jacket carries this endorsement by Anne Tyler: 'Barbara Pym is the rarest of treasures; she reminds us of the heartbreaking silliness of everyday life.' That, I think, is exactly right.

Friday, 1 August 2014

Bookmarks

There's a nice piece on the AbeBooks website about the strange things people have used as bookmarks and forgotten about - everything from forty $1,000 bills to a rasher of bacon (at least it wasn't a fried egg).

It puts me in mind of the time I opened a book and found some chap had cut off the end of his trouser-leg to use as a bookmark. 'Well,' I thought, 'there's a turn-up for the book.'

It puts me in mind of the time I opened a book and found some chap had cut off the end of his trouser-leg to use as a bookmark. 'Well,' I thought, 'there's a turn-up for the book.'

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)