I've been rereading Nabokov's Invitation to a Beheading - for the first time since I read it as a student 40-odd years ago. It's a rum one, more Kafkaesque than Nabokovian - in fact startlingly so, not least because Nabokov hadn't read any Kafka when he wrote it (in 1938). It tells the story of one Cincinnatus C, who finds himself imprisoned (in a castle-like gaol) under sentence of death for an obscure crime variously labelled as 'gnostical turpitude' or 'opacity' - essentially for being himself in a world in which he simply doesn't fit (and in which, as Nabokov describes it, no one fully human would want to fit). Nobody can understand why he is the way he is, and their incomprehension expresses itself either in contempt and cruelty or in flesh-crawling attempts to befriend him and 'bring him out of himself'. There's an early foreglimpse of Lolita in the shape of the gaoler's young daughter, but little else to link Invitiation to Nabokov's other works. It is certainly the least naturalistic of his novels, taking place in an unpredictable dream world of flimsy appearances. However, there are moments where the physical world comes into Nabokovian sharp focus, as with this brilliantly vivid description of a moth (so precise it can be identified as an Emperor Moth) in Cincinnatus' cell:

'It was only a moth, but what a moth! It was as large as a man's hand; it had thick, dark-brown wings with a hoary lining and grey-dusted margins; each wing was adorned in the centre with an eye-spot, shining like steel.

Its segmented limbs, in fluffy muffs, now clung, now unstuck themselves, and the upraised vanes of its wings, through whose underside the same staring spots and wavy grey pattern showed, oscillated slowly, as the moth, groping its way, crawled up the sleeve, while Rodion [the gaoler], quite panic-stricken, rolling his eyes, throwing away and forsaking his own arm, wailed, 'Take it off'n me! Take it off'n me!'

Upon reaching his elbow, the moth began noiselessly flapping its heavy wings; they seemed to outbalance its body, and on Rodion's elbow joint, the creature turned over, wings hanging down, still tenaciously clinging to the sleeve - and now one could see its brown, white-dappled abdomen, its squirrel face, the black globules of its eyes and its feathery antennae resembling pointed ears.

'Take it away!' impored Rodion, beside himself, and his frantic gesturing caused the splendid insect to fall off; it struck the table, paused on it in mighty vibration, and suddenly took off from its edge.'

That's wonderful. I don't suppose I shall ever reread Invitation to a Beheading again, but I'm glad to have returned to it this once.

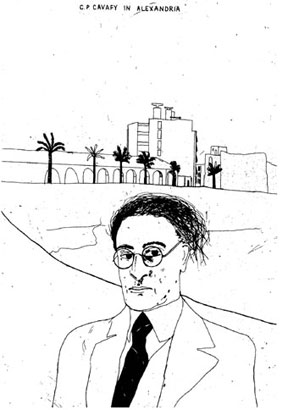

A toxic combination of overwork, a 'cold', hayfever and bad nights has left me in no fit state to do much blogging... However, I must mark the Big Day: the day on which, in 1863, the fascinating Alexandrian poet Constantin Cavafy was born - and the day on which, precisely 70 years later, he died. That doesn't often happen...

A toxic combination of overwork, a 'cold', hayfever and bad nights has left me in no fit state to do much blogging... However, I must mark the Big Day: the day on which, in 1863, the fascinating Alexandrian poet Constantin Cavafy was born - and the day on which, precisely 70 years later, he died. That doesn't often happen...