Here we go again - the expert professionals are finally discovering what is perfectly obvious to everyone else. You have to be very expert and very professional indeed not to realise that nursing is about caring for people as if they were, uh, people. This is obvious enough to the non-expert, non-professional cleaners who on some wards are the only people who do treat elderly patients as their fellow human beings. But not obvious, it seems, to the expert professionals, to whom it has come as a revelation. I suppose the upside of this is that it might mean that nursing finds its way back the values that used to prevail before it became a profession and a sub-academic discipline, rather than a vocation involving essentially practical expertise. Back to the future again?

I see that one of the report's recommendations is to bar the use of patronising language, such as 'old dear'. Enuff you sla me, as Molesworth would say. Once again they're missing the blindingly obvious - that the routine hospital practice of calling old people by their first names, uninvited, is the ultimate in patronising language, infantilising them and stripping them of their adult identity and dignity (and often adding to their confusion, as many people are not actually known by their first name). Simply changing to 'Mr' and 'Mrs' as the standard form of address would do more to change the ethos of hospital wards than any other single measure. And if it encouraged a wider return from first names to honorifics, that would be no bad thing.

Wednesday, 29 February 2012

Tuesday, 28 February 2012

Spellcheck

As ever at this time of year, I've been enjoying the blue wood anemones in Kensington Gardens. This year my enjoyment is tempered by my recent mortifying discovery that for many years - probably my whole literate life - I have been misspelling anemone, rendering it 'anenome' (as a quick search of this blog will confirm). I was absolutely convinced that 'anenome' was the right spelling, and was only shaken out of my certainty when Nige Jr presented me with incontrovertible proof that for all these years I had been wrong. This is, I suppose, what might be called a blind spot, and it makes me wonder how many more I have... I remember once, many years ago (student days), getting into a big stand-off with Appleyard over the spelling of a word - I can't remember what the word was, but we were both equally, unshakably convinced we had the right spelling. Soon an unfeasibly large (and therefore notional) sum of money was riding on the outcome, and at last the dictionary was consulted. On that occasion, it turned out I was right, but it could have gone either way. Nowadays I wouldn't bet on being right about anything.

As ever at this time of year, I've been enjoying the blue wood anemones in Kensington Gardens. This year my enjoyment is tempered by my recent mortifying discovery that for many years - probably my whole literate life - I have been misspelling anemone, rendering it 'anenome' (as a quick search of this blog will confirm). I was absolutely convinced that 'anenome' was the right spelling, and was only shaken out of my certainty when Nige Jr presented me with incontrovertible proof that for all these years I had been wrong. This is, I suppose, what might be called a blind spot, and it makes me wonder how many more I have... I remember once, many years ago (student days), getting into a big stand-off with Appleyard over the spelling of a word - I can't remember what the word was, but we were both equally, unshakably convinced we had the right spelling. Soon an unfeasibly large (and therefore notional) sum of money was riding on the outcome, and at last the dictionary was consulted. On that occasion, it turned out I was right, but it could have gone either way. Nowadays I wouldn't bet on being right about anything.

Monday, 27 February 2012

Back to Bland - and Beyond!

I didn't see our new national newspaper yesterday - the Sunday Sun or whatever it's called (I suspect my man kept it back to enjoy in the pantry) - but I understand the consensus view among the pundits is that it was 'bland'. This is excellent news. It may only be a blip, or Rupert Murdoch trying to present a squeaky-clean image to the world (and Leveson) - or it might be a sign of a more general movement back from the excesses of recent times towards something gentler, more in tune with the fundamental English character. This, you might remember, was until very recently marked by reticence, good manners, a sense of decency and fair play, a preference for muddling through (and grumbling), a distrust of innovation and excess - in a word, a tendency to something rather like blandness.

If the new Sun is looking back to the past, it is not alone, as this year's Oscars confirm, dominated as they are by the silent masterpiece The Artist, a return to the very beginnings of cinema in Hugo, and a portrayal of that now historic figure Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady. Even the recent Brit Awards were more retro than they have ever before been, more like an old boys' and girls' reunion than a celebration of a supposedly innovative, cutting-edge music. Could it be that we are seeing the dawn of a new Retroprogressive Age? Forward to the Past! You have nothing to lose but your News of the World (and you've already lost that).

If the new Sun is looking back to the past, it is not alone, as this year's Oscars confirm, dominated as they are by the silent masterpiece The Artist, a return to the very beginnings of cinema in Hugo, and a portrayal of that now historic figure Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady. Even the recent Brit Awards were more retro than they have ever before been, more like an old boys' and girls' reunion than a celebration of a supposedly innovative, cutting-edge music. Could it be that we are seeing the dawn of a new Retroprogressive Age? Forward to the Past! You have nothing to lose but your News of the World (and you've already lost that).

Friday, 24 February 2012

Birthday Betty

Betty Marsden(that's her between Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Horne in this jolly Beyond Our Ken photo)was born on this day in 1919. Radio listeners of a certain age would still instantly recognise her range of 'voices' - from Fanny Haddock (a barely exaggerated version of the the appalling celebrity cook Fanny Cradock) to the husky Daphne Whitethigh, the ancient actress Bea Clissold ('many, many, many times'), the Celia Johnson soundalike Dame Celia Molestrangler, Aussie ultra-feminist Judy Coolibar (no doubt an early role model for Germaine Greer), Buttercup Gruntfuttock (wife of J. Peasemold Gruntfuttock, the world's dirtiest dirty old man) and more...

Betty Marsden(that's her between Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Horne in this jolly Beyond Our Ken photo)was born on this day in 1919. Radio listeners of a certain age would still instantly recognise her range of 'voices' - from Fanny Haddock (a barely exaggerated version of the the appalling celebrity cook Fanny Cradock) to the husky Daphne Whitethigh, the ancient actress Bea Clissold ('many, many, many times'), the Celia Johnson soundalike Dame Celia Molestrangler, Aussie ultra-feminist Judy Coolibar (no doubt an early role model for Germaine Greer), Buttercup Gruntfuttock (wife of J. Peasemold Gruntfuttock, the world's dirtiest dirty old man) and more... Apparently Betty once told her fellow actress Dilys Laye that she wanted to die with a glass of gin in her hand - and she managed just that, one day after moving in to a home for elderly thespians. She died in the bar after subsiding into a chair so gracefully that she didn't spill a drop. What artistry!

Thursday, 23 February 2012

Mark the sequel...

So, having completed Dolores, Ivy sent the manuscript to Blackwood's, who promptly rejected it. Undeterred, she passed it on to her brother Noel (the first time he'd seen it), who enlisted the help of his friend and mentor, Oscar Browning ('a man of bad character and European fame,' according to Rupert Brooke), to get it published. But even O.B. failed to interest his publisher in Ivy's manuscript. In the end, it seems that a slightly revised version of the novel was offered to Blackie's, who were not keen, but agreed to print a run of 1,050 copies if £150 was paid by way of subsidy. This was duly agreed, and the book came out in February 1911. But here's the surprising thing - it received some very good reviews. Walter de la Mare, writing anonymously in the TLS, was encouraging, and predicted 'something really striking from the young author' in future - he was right there, but probably not in the way he envisaged, and it would be 14 years before it happened. Still more gratifying to ICB was an almost effusive review in the Daily Mail, which ended with the assertion that 'Dolores is literature; of that no competent critic can have any doubt'. By the end of the year, the edition had all but sold out, Blackie's was clearing its warehouse, and Ivy was offered the hundred or so remaindered copies. According to Olivia Manning, she bought them all and kept them locked up in a cupboard for the rest of her life. Whether this is true or not, no one knows.

Wednesday, 22 February 2012

'This oft-lived heart-throb'

Reading Ivy When Young, Hilary Spurling's superb (and, unlike many a biography, necessary) 1974 account of Ivy Compton-Burnett's early years, I am discovering much. Not least that, a full 14 years before her acknowledged canon began with Pastors and Masters (1925), she wrote a first novel called Dolores, which is not only wholly unlike her later work but, by the sound it, pretty well unreadably awful. It's the story of a young woman's strenuous self-abnegation for the sake of 'service to her kin', with much clenching of hands, trembling of limbs, whitening of lips and furrowing of brow as Dolores wrestles endlessly with her conscience. This kind of thing derives from the novels of such now all but forgotten writers as Charlotte M. Yonge and Mrs Humphry Ward. But, as Hilary Spurling demonstrates at length, it is the baleful influence of George Eliot that hangs heaviest over the novel, some passages seeming so close as to be almost plagiarised. Both George Eliot and the ICB of Dolores 'assume the same stiffish intimacy with the reader, and alternate between lugubrious solemnity and a vivid, mocking, generally patronising gaiety at the expense of the lower orders'. But Ivy adopts novelettish turns of phrase that Eliot would have sniffed at - 'this oft-lived heart-throb', 'the prime knit with a nobler soul' - and 'the book reads at times as though she were alternately translating from the Latin... and coining her own Homeric epithets'. Well, I certainly feel no desire to read Dolores, a book disowned and suppressed by its author (though if I came across it in a charity shop, I'd snap it up - it's quite a rarity) - but I do have a strong urge to read on in Hilary Spurling's biography, and discover how Ivy Compton-Burnett got from writing the dire Dolores to being the author of her later, so wholly different works. What happened?

Tuesday, 21 February 2012

All Hail, Ashton!

This handsome chap is the actor Ashton Kutcher. When, back in 2009, I wrote this game-changing post, Kutcher was known chiefly for being married to a rather older lady and appearing in a string of forgettable slacker comedies - and rather less known for his occasional adoption of the cravat. I tipped him for great things - and now, sure enough, he has delivered. Kutcher is huge! Stepping into Charlie Sheen's shoes as star of Two And A Half Men, he has not only secured a mighty pay packet and a huge audience, but also revealed himself to be an absolutely terrific comic actor. He's not playing the Sheen role, of course - he's an entirely different character, accidental billionaire Walden Schmidt. Walden is infinitely more likeable than Charlie, and, though he can sometimes behave almost as badly, he does it in a benign, absent-minded, forgivable way. Much of the darkness at the show's core has now seeped into Alan, who is developing very interestingly (while Jake, the formerly ill-favoured lump of a boy, is turning strangely hunky). Kutcher's presence - sometimes it's more like absence - changes everything and, in a completely laid-back way, dominates everything. It's a masterclass in relaxed, perfectly timed comic acting. All hail, Ashton Kutcher - living proof of the power of the cravat!

This handsome chap is the actor Ashton Kutcher. When, back in 2009, I wrote this game-changing post, Kutcher was known chiefly for being married to a rather older lady and appearing in a string of forgettable slacker comedies - and rather less known for his occasional adoption of the cravat. I tipped him for great things - and now, sure enough, he has delivered. Kutcher is huge! Stepping into Charlie Sheen's shoes as star of Two And A Half Men, he has not only secured a mighty pay packet and a huge audience, but also revealed himself to be an absolutely terrific comic actor. He's not playing the Sheen role, of course - he's an entirely different character, accidental billionaire Walden Schmidt. Walden is infinitely more likeable than Charlie, and, though he can sometimes behave almost as badly, he does it in a benign, absent-minded, forgivable way. Much of the darkness at the show's core has now seeped into Alan, who is developing very interestingly (while Jake, the formerly ill-favoured lump of a boy, is turning strangely hunky). Kutcher's presence - sometimes it's more like absence - changes everything and, in a completely laid-back way, dominates everything. It's a masterclass in relaxed, perfectly timed comic acting. All hail, Ashton Kutcher - living proof of the power of the cravat!

Monday, 20 February 2012

A Pyramid in Sussex

This is but one of a fine set of follies built by the 18th-century eccentric 'Mad Jack' Fuller in and around the Sussex village of Brightling (this one was to serve as his mausoleum, so at least it had a purpose). Fuller, born on this day in 1757, preferred to be known as 'Honest John', but spent much of his time energetically living up to the 'Mad Jack' nickname. He inherited a fortune at the age of 20, and at 23 took his seat in the Commons, where he distinguished himself by being even more drunk than most of his fellow MPs, and by speaking up vigorously in defence of slavery, the foundation of much of his family's wealth. However, 'Mad Jack' was also an active patron of science and the arts, supporting the Royal Institution and commissioning paintings from Turner. And he did many good works, building the Belle Tout lighthouse at Beachy Head, giving Eastbourne its first lifeboat, and buying Bodiam Castle to save it from destruction. But it is for his follies that he will always be remembered - and a weird and wonderful collection they are... If you find yourself in the vicinity - Brightling is near Robertsbridge and not far from Battle - do take a look around. It's a surprisingly remote-feeling spot, high on the Sussex Weald, with wide views in parts and a contrasting hedged-in feeling in others, and a tang of salt in the air. And the tour of Mad Jack's follies makes for one of the strangest walks that southern England has to offer.

This is but one of a fine set of follies built by the 18th-century eccentric 'Mad Jack' Fuller in and around the Sussex village of Brightling (this one was to serve as his mausoleum, so at least it had a purpose). Fuller, born on this day in 1757, preferred to be known as 'Honest John', but spent much of his time energetically living up to the 'Mad Jack' nickname. He inherited a fortune at the age of 20, and at 23 took his seat in the Commons, where he distinguished himself by being even more drunk than most of his fellow MPs, and by speaking up vigorously in defence of slavery, the foundation of much of his family's wealth. However, 'Mad Jack' was also an active patron of science and the arts, supporting the Royal Institution and commissioning paintings from Turner. And he did many good works, building the Belle Tout lighthouse at Beachy Head, giving Eastbourne its first lifeboat, and buying Bodiam Castle to save it from destruction. But it is for his follies that he will always be remembered - and a weird and wonderful collection they are... If you find yourself in the vicinity - Brightling is near Robertsbridge and not far from Battle - do take a look around. It's a surprisingly remote-feeling spot, high on the Sussex Weald, with wide views in parts and a contrasting hedged-in feeling in others, and a tang of salt in the air. And the tour of Mad Jack's follies makes for one of the strangest walks that southern England has to offer.

Sunday, 19 February 2012

Already

Walking through the park earlier today, I noticed a small family - father, mother, small daughter - crouching down gazing intently at a clump of Dwarf Iris in a sunny spot. The man was taking a photograph - and no wonder, for there, perching decoratively on a flowerhead, was a Red Admiral! It was a slightly faded specimen, and flew off within a minute and was lost to view - but what a joyful surprise... The butterfly year has begun - already, nearly a full month earlier than last year.

Walking through the park earlier today, I noticed a small family - father, mother, small daughter - crouching down gazing intently at a clump of Dwarf Iris in a sunny spot. The man was taking a photograph - and no wonder, for there, perching decoratively on a flowerhead, was a Red Admiral! It was a slightly faded specimen, and flew off within a minute and was lost to view - but what a joyful surprise... The butterfly year has begun - already, nearly a full month earlier than last year.

Friday, 17 February 2012

Raviliouses, Bawdens and the Queen of Puddings

I'm enjoying a very beautiful book called Ravilious In Pictures: A Country Life (for which my thanks to Mrs N, who also bought me its ideal companion volume, Edward Bawden's London). A Country Life is one of a series of Eric Ravilious volumes published by The Mainstone Press. Each opening offers a reproduction of a Ravilious watercolour opposite a page of text setting the picture in context in the artist's life. The story begins with Ravilious and his wife Tirzah living with Edward Bawden and his wife Charlotte in creative harmony in Brick House, a large run-down Georgian house in the village of Great Bardfield in Essex. 'There was no water,' recalled Edward Bawden, 'no electricity, no drains. Very exciting. If you're young!' Ravilious's pictures of the house and its surroundings are suffused with the contenment of a companionable new life in the country, and the two couples seem to have been very happy together. But the idyll had to end. After Bawden and Ravilious had a successful joint exhibition and made some money, Charlotte became pregnant, and Eric and Tirzah started looking for a house of their own.

I'm enjoying a very beautiful book called Ravilious In Pictures: A Country Life (for which my thanks to Mrs N, who also bought me its ideal companion volume, Edward Bawden's London). A Country Life is one of a series of Eric Ravilious volumes published by The Mainstone Press. Each opening offers a reproduction of a Ravilious watercolour opposite a page of text setting the picture in context in the artist's life. The story begins with Ravilious and his wife Tirzah living with Edward Bawden and his wife Charlotte in creative harmony in Brick House, a large run-down Georgian house in the village of Great Bardfield in Essex. 'There was no water,' recalled Edward Bawden, 'no electricity, no drains. Very exciting. If you're young!' Ravilious's pictures of the house and its surroundings are suffused with the contenment of a companionable new life in the country, and the two couples seem to have been very happy together. But the idyll had to end. After Bawden and Ravilious had a successful joint exhibition and made some money, Charlotte became pregnant, and Eric and Tirzah started looking for a house of their own.All perfectly reasonable - but the painter and engraver Douglas Percy Bliss would have it that 'there was a rift between the couples caused by an excess of Queen of Puddings'! This, according to Bliss, was the only pudding Tirzah could make, and everybody got heartily sick of it.

I don't believe that story, for two reasons. One: Queen of Puddings is not especially easy to make, so if Tirzah could manage that, she could manage any number of other puddings. And two: Queen of Puddings is a very fine classic pudding, of the kind that sends pudophiles into raptures (as here)... My mother used to make Queen of Puddings quite often, and insisted that it shouldn't be confused with Queen's Pudding. However, my online researches suggest that they are one and the same. Perhaps one of the foodies over on The Dabbler could clarify, or even take up the theme...

Thursday, 16 February 2012

Who Drew This?

Since no one's posting comments any more (except over on The Dabbler), perhaps it's time for a competition. So - can you guess which well known writer drew the cartoon above? The answer is surprising, but I suspect there might be a few out there who know it. If not, all guesses are welcome...

The caption, by the way, is 'Do you have any books the faculty doesn't particularly recommend?'

Wednesday, 15 February 2012

Tuesday, 14 February 2012

The Boz Ball

On a more cheerful note - on this day (Ss Cyril and Methodius - or, if you insist, St Valentine) in 1842, the literary superstar Charles Dickens was royally entertained in New York with the 'Boz ball' at the Park Theater. For this huge event with some 3,000 guests (at $2 a ticket), the city's finest caterer, Thomas Downing, was pressed into service, and he surely rose to the occasion, creating a centrepiece of 50,000 - yes, fifty thousand - oysters. The bill of fare also included 40 hams, 76 tongues, 50 rounds of beef, 50 jellied turkeys, 50 pairs of chickens and 25 of ducks, 2,000 fried mutton chops (served cold), 10,000 sandwiches and '12 floating swans - a new device' (what on earth was that?). This lot was followed by 350 quarts of jelly and blancmange, 300 quarts of ice cream, 300lb of candy mottoes, 2,000 candy kisses, 25 pyramids and 'Ladies Fingers in thousands'. All washed down with two hogsheads of lemonade, 60 gallons of tea, one and half barrels of port, 150 gallons (yes, gallons) of Madeira, and unlimited claret and coffee.

On a more cheerful note - on this day (Ss Cyril and Methodius - or, if you insist, St Valentine) in 1842, the literary superstar Charles Dickens was royally entertained in New York with the 'Boz ball' at the Park Theater. For this huge event with some 3,000 guests (at $2 a ticket), the city's finest caterer, Thomas Downing, was pressed into service, and he surely rose to the occasion, creating a centrepiece of 50,000 - yes, fifty thousand - oysters. The bill of fare also included 40 hams, 76 tongues, 50 rounds of beef, 50 jellied turkeys, 50 pairs of chickens and 25 of ducks, 2,000 fried mutton chops (served cold), 10,000 sandwiches and '12 floating swans - a new device' (what on earth was that?). This lot was followed by 350 quarts of jelly and blancmange, 300 quarts of ice cream, 300lb of candy mottoes, 2,000 candy kisses, 25 pyramids and 'Ladies Fingers in thousands'. All washed down with two hogsheads of lemonade, 60 gallons of tea, one and half barrels of port, 150 gallons (yes, gallons) of Madeira, and unlimited claret and coffee.A good time was had by all - not least by Dickens and his wife, who was still at this time in favour with the great man - but it was not to last. Dickens was soon finding it irksome to have crowds following him everywhere and at all times, and, as he found out more about them, he became deeply disenchanted with American politics and appalled by American manners (not to mention resentful of wholesale American piracy of his works). After publication of the scathing American Notes and the equally unflattering (in its American scenes) Martin Chuzzlewitt, Dickens and America fell out spectacularly. Relations were restored, however, late in his career when Dickens returned to America to give some of his hugely popular public readings, and to revel again in the adoration of the American public. But by then he wasn't up to another Boz Ball banquet.

A Sad Sight

This lunchtime, I was walking by the water garden in Kensington Gardens when one of the gardeners passed by, holding a wide wooden rake before him. Cradled between the handle and the upturned tines was a dead Moorhen, bedraggled but still beautiful, its olive-green legs in the air. He had found it, he told me, under the ice, frozen stiff. We briefly mourned the 'poor thing' and its sad fate, and he took it away to dispose of its mortal remains. This winter has been very late, but bitter.

Monday, 13 February 2012

The Towers of Trebizond: Rum

Well, I have finished reading Rose Macaulay's The Towers of Trebizond - and what a rum do it is. Entertaining, colourful, involving, often laugh-aloud funny, packed with ideas and hugely readable - but undeniably rum, and very much of its time (1956 to be precise). I mean - a novel about a pair of highly educated, upper-class English eccentrics of very High Church views travelling around Turkey with the aim (among others) of converting Turkish womankind to High Anglicanism, which would liberate them to wear hats and sit around in cafes playing tric-trac all day, just like the men... It is hard to imagine such a novel being published in today's, er, climate. In fact, when it was written the climate was chilled not by anything to do with Islam but by the Cold War, which feeds into the story in often surprising ways.

It is indeed a novel full of surprises - one that starts off appearing to be a jolly, lightly satirical comedy set in a Turkey where every other English visitor is either spying or writing a book. It then starts developing all manner of offshoots, as the narrator, Laurie, niece of the camel-owning Aunt Dot (who, along with her fellow would-be missionary, Father Chantry-Pigg, is a great comic character), carries us along with her into realms of thought, speculation and fantasy on themes related to the ancient world - in particular the Byzantine Empire, of which Trebizond was the last stronghold - Christianity, love, sin, grace, East and West, espionage, Church history, camels, apes, adultery... Her artless, almost girlish narrative voice, trotting breathlessly from phrase to phrase in long sentences strung together by 'and's, propels everything along most enjoyably, and makes a piquant contrast to her subject matter when that turns serious - as it increasingly does after a dramatic turn in the narrative at around the halfway point. Now Laurie herself takes centre stage, and what began as a comedy turns into something quite different, as we find out more about her blissful but guilty relationship with a married man, and follow her attempts to achieve some kind of grace, or at least make herself eligible for it. The focus is more and more on her 'brand of flimsy and broken-backed but incurable religion' - to the extent that, towards the end of the book, she devotes almost a whole chapter to theological questions, particularly Predestination and Election and the problematic 39 Articles of the Church of England.

And then, having given the impression that her story is going to peter out amiably and inconclusively, she delivers a devastating shock in the very last chapter that changes everything utterly, and delivers an ending that could hardly be more different from that famous opening: 'Take my camel, dear...'.

I think I can honestly say I have never read another novel quite like The Towers of Trebizond. It is a true original.

It is indeed a novel full of surprises - one that starts off appearing to be a jolly, lightly satirical comedy set in a Turkey where every other English visitor is either spying or writing a book. It then starts developing all manner of offshoots, as the narrator, Laurie, niece of the camel-owning Aunt Dot (who, along with her fellow would-be missionary, Father Chantry-Pigg, is a great comic character), carries us along with her into realms of thought, speculation and fantasy on themes related to the ancient world - in particular the Byzantine Empire, of which Trebizond was the last stronghold - Christianity, love, sin, grace, East and West, espionage, Church history, camels, apes, adultery... Her artless, almost girlish narrative voice, trotting breathlessly from phrase to phrase in long sentences strung together by 'and's, propels everything along most enjoyably, and makes a piquant contrast to her subject matter when that turns serious - as it increasingly does after a dramatic turn in the narrative at around the halfway point. Now Laurie herself takes centre stage, and what began as a comedy turns into something quite different, as we find out more about her blissful but guilty relationship with a married man, and follow her attempts to achieve some kind of grace, or at least make herself eligible for it. The focus is more and more on her 'brand of flimsy and broken-backed but incurable religion' - to the extent that, towards the end of the book, she devotes almost a whole chapter to theological questions, particularly Predestination and Election and the problematic 39 Articles of the Church of England.

And then, having given the impression that her story is going to peter out amiably and inconclusively, she delivers a devastating shock in the very last chapter that changes everything utterly, and delivers an ending that could hardly be more different from that famous opening: 'Take my camel, dear...'.

I think I can honestly say I have never read another novel quite like The Towers of Trebizond. It is a true original.

Sunday, 12 February 2012

Aere Perennius

There's a happy postscript to last November's sorry tale of Desecration. A local scrap merchant has, at his own expense, replaced the stolen brass plaques from the pillaged war memorial with tablets of Portland stone. What's more, the names of the fallen are carved thereon with classical perfection. This is a hugely cheering outcome - all is not lost, indeed. The philanthropic scrap merchant is also actively involved in a campaign to clean up the practices of his rogue-prone trade. I take my hat off to him - and meanwhile, anyone in the south London area with scrap to dispose of, take your business straight to B. Nebbett & Son, and to no other.

Saturday, 11 February 2012

A-Ha!

Here's something you don't come across every day: a good news story out of North Korea - one that comes, what's more, by way of Norwegian Eighties pop heart-throb Morten Harket, and his fellow Morten, Morten Traavik. Looking at the video, it's easy to see why Morten was so impressed - they are amazing! There's a longer and better-quality video on YouTube - here. I find that the more you play it, the more beautiful and cheering it becomes, and the more touching, especially at those moments where the smiles break through. These musicians are loving it. As for that setting, with the snowy painting and the big pot of fake sunflowers... And isn't that someone's mobile going off at the end?

Friday, 10 February 2012

Thursday, 9 February 2012

Books on Trains

The printed word lives on, not least on trains, where the majority of passengers (at least on the routes I frequent) engage in some kind of reading in the course of their journey. Much of it is of newspapers - especially the commuter-friendly freesheet Metro - and an increasing amount is of ebooks, but there is still much reading of proper printed books. And when I see someone reading a proper printed book, I am always curious to find out what it is - in fact I can't help myself. My surreptitious researches into this matter have thrown up some surprises, not least the remarkable amount of devotional reading that goes on on trains, even in this supposedly secular age - the Bible (and Quran) in various forms, prayerbooks and spiritual manuals galore. Sightings of the literary classics, too, are more frequent than might be expected, though I see no evidence of a bicentennial surge in Dickens reading yet...

This morning I found myself sitting opposite a very elegant, well-turned-out lady of, I guess, around 40, who was reading with interest a hardback book that had clearly been around for a few decades (this in itself is unusual in an age of ephemeral paperbacks). What could it be? Eventually the book fell at the right angle for me to make out its title. It was The Creed In Slow Motion by Ronald Knox - priest, detective novelist, radio personality, scholar, Catholic convert, friend to all, and yes, one of those Knox Brothers, whose joint biography by their brilliant niece, Penelope Fitzgerald, I read not long ago. Knox wrote The Creed In Slow Motion during the Hitler War, when he found himself serving as chaplain of a girls' school where students were being sheltered. Running out of homilies (as one does), he set about writing some more, in the form of a step-by-step explication of the Apostles' Creed, which was in due course published as The Creed In Slow Motion. And there it was, being read by the elegant lady opposite me on my commuter train nearly 70 years later. She alighted at Victoria - handy, of course, for Westminster Cathedral, and the offices of The Tablet...

I reckon The Creed In Slow Motion must be worth 100 points in the I-Spy Books on Trains book.

This morning I found myself sitting opposite a very elegant, well-turned-out lady of, I guess, around 40, who was reading with interest a hardback book that had clearly been around for a few decades (this in itself is unusual in an age of ephemeral paperbacks). What could it be? Eventually the book fell at the right angle for me to make out its title. It was The Creed In Slow Motion by Ronald Knox - priest, detective novelist, radio personality, scholar, Catholic convert, friend to all, and yes, one of those Knox Brothers, whose joint biography by their brilliant niece, Penelope Fitzgerald, I read not long ago. Knox wrote The Creed In Slow Motion during the Hitler War, when he found himself serving as chaplain of a girls' school where students were being sheltered. Running out of homilies (as one does), he set about writing some more, in the form of a step-by-step explication of the Apostles' Creed, which was in due course published as The Creed In Slow Motion. And there it was, being read by the elegant lady opposite me on my commuter train nearly 70 years later. She alighted at Victoria - handy, of course, for Westminster Cathedral, and the offices of The Tablet...

I reckon The Creed In Slow Motion must be worth 100 points in the I-Spy Books on Trains book.

Wednesday, 8 February 2012

'London...'

I pass this on simply because it made me laugh rather a lot. It's a fine deadpan spoof of a certain style of 'serious' TV documentary, with the odious presenter trying very hard to be Jonathan Meades, and ending up more like a younger Ed Reardon. Sadly it does not do much to improve the image of the cravat. Enjoy...

Olimpicks News

More than once, as regular readers will know, I have looked back fondly to the early 'modern' Olympic Games, contrasting these jolly and eminently civilised affairs with the joyless hypertrophied big-money fascistic spectacle about to be inflicted on the unfortunate city of London. What I had not realised was that the first Olympic revival took place not in the 19th century, but exactly 400 years ago, in 1612, near Chipping Camden in the Cotswolds. They were staged, with royal approval, by one Robert Dover, a lawyer, author and wit, for motives which remained unclear to him. As he recalled,

'I cannot tell what planet ruled, when I

First undertook this mirth, this jollity,

Nor can I give account to you at all,

How this conceit into my brain did fall.

Or how I durst assemble, call together

Such multitudes of people as come hither.'

Events in the Cotswold Olimpicks included, as well as a bit of running and jumping, horse-racing, coursing with hounds, dancing, sledgehammer throwing and fighting with swords, cudgels and quarterstaffs. For the more sedentary, there were games of chess and cards (for small stakes), and food and drink galore. Cannon were fired from a temporary wooden structure known as Dover Castle to signal the start of events, and much fun was had by all.

Naturally, the games fell out of favour as the Puritans made their presence increasingly felt, and they were suspended altogether for the duration of the Civil War and Commonwealth. Revived at the Restoration, they gradually declined into a drunken rout, before being stopped altogether in 1852. But that was not the end of the story: the games were staged again for the Festival of Britain, and have been held every year since 1966, though in a somewhat different form from Dover's original games. Events now include tug-of-war, shin-kicking, gymkhana, piano smashing and, of course, dwile flonking (for an explanation of which, Wikipedia cannot be bettered).

The irony in all this is that the Cotswold Olimpicks were mentioned in British Olympic Association's application for the 2012 Games, as 'the first stirrings of Britain's Olympic beginnings'. Let us hope it was not this detail that swayed the IOC in London's favour - that would be too sad.

Tuesday, 7 February 2012

Most Tweeted

The Super Bowl, an American sporting event that believes itself to be the biggest in the world (conveniently overlooking the Tour de France), has set a new record - as the 'most tweeted sporting event ever'. The facts and figures are here, along with a list of some other much-tweeted events.

It's things like this that convince me the Twitter phenomenon is getting out of hand. For myself, I've always been agin it, on the grounds that there's more than enough wittering in the world already, and I don't intend to make matters any worse. I can see no attraction in the medium, except perhaps in developing it as a kind of ultra-tight prose haiku, but life's too short, and so are tweets. Twitter has, of course, been a phenomenal success - but when it comes to tweeting on such a phenomenal scale in the course of a fast-moving sporting event, you have to wonder what's going on. Are we reaching the point when people won't believe they're having (or have had) an experience unless they're tweeting about it? Will the tweet become more important, more real, than the experience itself? It's something akin to those camera-toting tourists who never look at anything except through the camera's lens, and won't believe they've been anywhere unless they have the photographs to prove it. The compulsion to tweet can be seen as a demotic version of a condition that afflicts writers and journalists - the inability to experience anything without simultaneously turning it into words. In these circumstances, words - whether tweeted or composed in a writerly way in the head - come between us and what we are perceiving and should be experiencing. What a joy it would be to return to the world I grew up in, where a person could wander at large entirely unconnected and incommunicado, with no means of communicating with anyone, except perhaps by seeking out a red telephone box. I'm sure we experienced the world in a more direct, uncomplicated and relaxed way then, when we were not busy compulsively translating it into something else and feverishly communicating with the immaterial world contained in a little box in the palm of the hand.

It's things like this that convince me the Twitter phenomenon is getting out of hand. For myself, I've always been agin it, on the grounds that there's more than enough wittering in the world already, and I don't intend to make matters any worse. I can see no attraction in the medium, except perhaps in developing it as a kind of ultra-tight prose haiku, but life's too short, and so are tweets. Twitter has, of course, been a phenomenal success - but when it comes to tweeting on such a phenomenal scale in the course of a fast-moving sporting event, you have to wonder what's going on. Are we reaching the point when people won't believe they're having (or have had) an experience unless they're tweeting about it? Will the tweet become more important, more real, than the experience itself? It's something akin to those camera-toting tourists who never look at anything except through the camera's lens, and won't believe they've been anywhere unless they have the photographs to prove it. The compulsion to tweet can be seen as a demotic version of a condition that afflicts writers and journalists - the inability to experience anything without simultaneously turning it into words. In these circumstances, words - whether tweeted or composed in a writerly way in the head - come between us and what we are perceiving and should be experiencing. What a joy it would be to return to the world I grew up in, where a person could wander at large entirely unconnected and incommunicado, with no means of communicating with anyone, except perhaps by seeking out a red telephone box. I'm sure we experienced the world in a more direct, uncomplicated and relaxed way then, when we were not busy compulsively translating it into something else and feverishly communicating with the immaterial world contained in a little box in the palm of the hand.

CD200

This is it then. The big day. The bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens, one of the key dates in a year of celebrations that will no doubt include much sentimental silliness - and Dickens would have no objection at all to that.

This is it then. The big day. The bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens, one of the key dates in a year of celebrations that will no doubt include much sentimental silliness - and Dickens would have no objection at all to that.Dickens's works - or some essence of them - have penetrated deeper into the national consciousness than anyone's except Shakespeare's. This despite the fact that - as with Shakespeare - the actual works are less and less read (though Shakespeare's are staged probably more than ever). It will be a good thing if the bicentenary encourages people to actually read Dickens's novels; I suspect they might be shocked by what they find. They are big baggy monsters, dense, complex, resistant and fricative. They are also, almost all of them, deeply flawed - by wild implausibilities, sickly sentimentality, preachy rhetoric, feebly conceived heroes and heroines, a compulsive urge to achieve a Happy Ending... But none of this matters, because the sheer imaginative power of Dickens in full flow disarms all criticism. The force of his characterisation - not only of people but of landscapes, even inanimate objects - and the vitality and abundance of his comedy are such that they carry all before them. It is very sad that most children who come through the state school system have only read Hard Times, one of the least satisfactory of his works, selected largely - one suspects - for its relative brevity and its easily deconstructed 'message'. Dickens - essentially a comic writer - was at his weakest when he ventured into the world of 'ideas', as he does in Hard Times. His world was entirely concrete and intensely, wonderfully, often grotesquely real. It is worth rediscovering in this bicentenary year.

Sunday, 5 February 2012

A Butterfly Season

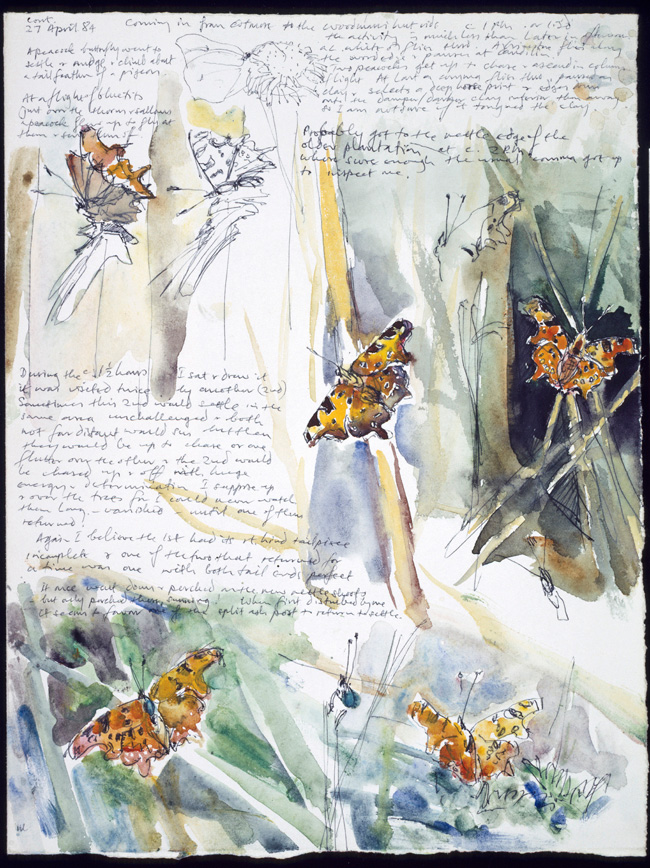

Thanks to the generosity of my cousin - with whom I was staying in Derbyshire earlier in the weekend - I have a fine new butterfly book to get me through the winter. Butterfly Season 1984 by David Measures is a beautiful volume, an illustrated journal of a season spent observing, painting and drawing butterflies as they lived their brief lives in a variety of habitats, most of them close to the artist's home in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. Measures, who became fascinated by butterflies after he began studying the iridescent properties of their wings, was the first artist to paint these lovely insects not as minutely denoted dead specimens but as living creatures in their environment - and in flight. This was an all but impossible challenge to which Measures rose with brilliant success, not by creating finished paintings but by catching the fleeting impressions which are all that we usually get of those restless beauties, the butterflies. He worked en plein air, chasing about after his flitting subjects, carrying only a few sheets of paper on a drawing board and a small box of watercolours, and working often with his fingers and nails, with spit to thin his colours. Often, to get close to the butterflies, he worked crouching, kneeling or lying down. If his subject flew off - as they do - he would give chase, reposition himself and try again, until it flew off again...

Thanks to the generosity of my cousin - with whom I was staying in Derbyshire earlier in the weekend - I have a fine new butterfly book to get me through the winter. Butterfly Season 1984 by David Measures is a beautiful volume, an illustrated journal of a season spent observing, painting and drawing butterflies as they lived their brief lives in a variety of habitats, most of them close to the artist's home in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. Measures, who became fascinated by butterflies after he began studying the iridescent properties of their wings, was the first artist to paint these lovely insects not as minutely denoted dead specimens but as living creatures in their environment - and in flight. This was an all but impossible challenge to which Measures rose with brilliant success, not by creating finished paintings but by catching the fleeting impressions which are all that we usually get of those restless beauties, the butterflies. He worked en plein air, chasing about after his flitting subjects, carrying only a few sheets of paper on a drawing board and a small box of watercolours, and working often with his fingers and nails, with spit to thin his colours. Often, to get close to the butterflies, he worked crouching, kneeling or lying down. If his subject flew off - as they do - he would give chase, reposition himself and try again, until it flew off again...Measures' first butterfly book (which I've had for years) was the delightful Bright Wings of Summer, a general introduction to the life of butterflies, with illustrations that were like nothing I, or anyone else, had seen before - vivid impressions of, as he puts it, 'the outdoor, free-flying, daytime activities of butterflies in the wild'. In Butterfly Season, he published his unedited field notes with the painted sheets from his notebook, all dashed off on the spot, with more or less impressionistic sketches of the butterflies, depending on how long he had sight of them - he would always stop when a subject flew off and was lost, never finishing from memory, for fear of generalising and falsifying. The sheets are also embellished with the handwritten notes Measures took at the time, and, to complete the evocation of time and place, washes and sketched-in details loosely denoting the setting in which the butterflies were watched and painted. As Julian Spalding writes in the introduction, 'his eye is not taking in just [the butterflies], incredibly difficult though this is, but the whole scene, the quality of light, the type of vegetation, even the alertness of the butterfly itself to its surroundings, to the antics of another insect or to any sudden movement that could be dangerous...'

David Measures died last year. There is a fine obituary here.

Thursday, 2 February 2012

False Past, True Art

Over on The Dabbler, I"m musing on Television's False Past.

Yesterday I went to the cinema for the first time in ages, to see The Artist, the French 'silent' film that is sweeping all before it. All I can say is that it was sheer delight, a true fully formed work of art, most definitely not a pastiche. The director Michel Hazanavicius has clearly immersed himself totally in 'silent' film, learnt and absorbed its language, and put it to brilliant - and very funny - use. Also both the leads are sensational, and sensationally good-looking, which helps. I hope the success of The Artist sparks a revival of the 'silent' movie - which is emphatically not a film trying to get by without recorded dialogue but a wonderfully expressive and immersive art form in itself. It is where the soul of cinema resides.

Yesterday I went to the cinema for the first time in ages, to see The Artist, the French 'silent' film that is sweeping all before it. All I can say is that it was sheer delight, a true fully formed work of art, most definitely not a pastiche. The director Michel Hazanavicius has clearly immersed himself totally in 'silent' film, learnt and absorbed its language, and put it to brilliant - and very funny - use. Also both the leads are sensational, and sensationally good-looking, which helps. I hope the success of The Artist sparks a revival of the 'silent' movie - which is emphatically not a film trying to get by without recorded dialogue but a wonderfully expressive and immersive art form in itself. It is where the soul of cinema resides.

Wednesday, 1 February 2012

A New Wonder

The Victoria & Albert Museum is, of course, full of wonders - wonder we Londoners tend to take for granted. It's been a few years since I last visited, but I was there yesterday, enjoying the medieval galleries and finding out about enamelling (there's a fascinating video showing how it's done - or how one enamelling technique is done). After an hour and half or so among the medieval marvels, I was nearing overload, so I headed for the cafe for refreshment. On my way, I noticed a small side gallery labelled Golden Spider Silk Cape - and there it was, a new wonder, woven only last year! It is a thing of quite startling beauty, a cape with an ecclesiastical flavour (but not intent), entirely woven from the naturally golden silk of Madagascan orb-weaver spiders, and beautifully embroidered with complex patterns of flowers and, of course, spiders. It is an astonishing sight, with a texture and luminescence that lift it into a realm above the finest silkmoth silk (it is also very much lighter, and stronger).

The Victoria & Albert Museum is, of course, full of wonders - wonder we Londoners tend to take for granted. It's been a few years since I last visited, but I was there yesterday, enjoying the medieval galleries and finding out about enamelling (there's a fascinating video showing how it's done - or how one enamelling technique is done). After an hour and half or so among the medieval marvels, I was nearing overload, so I headed for the cafe for refreshment. On my way, I noticed a small side gallery labelled Golden Spider Silk Cape - and there it was, a new wonder, woven only last year! It is a thing of quite startling beauty, a cape with an ecclesiastical flavour (but not intent), entirely woven from the naturally golden silk of Madagascan orb-weaver spiders, and beautifully embroidered with complex patterns of flowers and, of course, spiders. It is an astonishing sight, with a texture and luminescence that lift it into a realm above the finest silkmoth silk (it is also very much lighter, and stronger).The cape hangs resplendent in a display case in the centre of the small (too small) gallery, with ancillary material - including a video and a wonderful large-scale working drawing and pattern, much embellished with quotations related to spiders and their silk. Happily, as is often the case these days, most of the people - and there were many, most of them very excited - gravitate to the ancillary stuff, leaving space for those who want to take a good look at the thing itself, the wondrous cape. And there's a handsomely produced and informative book about the whole venture available for just £5. The book looks back at spiders and their silk in myth and metaphor, and traces the history of earlier attempts at weaving with their silk. It even finds space for this wonderful image from a letter of Keats to John Hamilton Reynolds:

'Now it appears to me that almost any Man may like the Spider spin from his own inwards his own airy Citadel - the points of twigs and leaves on which the Spider begins her work are few, and she fills the air with beautiful circuiting; Man should be content with as few points to tip with the fine Webb of the Soul and weave a tapestry Empyrean - full of Symbols for his spiritual eye, of softness for his spiritual touch, of space for his wanderings.'

The makers of the cape sum up their aim thus:

'Our objective has been to arouse a real sense of wonder in a world that too often admires the facile and meretricious.'

They have wonderfully succeeded.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)