In her latest book of essays (Alive, Alive, Oh!), Diana Athill, who turns 98 later this month, celebrates one of the compensations of old age - being able to view art exhibitions from a wheelchair. The crowds, she says, part before a wheelchair like the waves of the Red Sea, enabling her to settle down before the pictures and enjoy them close up, unobstructed and at leisure - an enviable advantage at a popular blockbuster exhibition. She recalls as one of her most blissful artistic experiences sitting enraptured before Matisse's Red Dance.

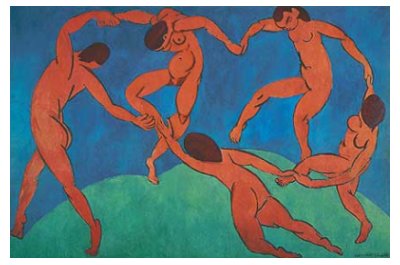

This would have been the painting usually known as Dance (1910), which came to the Royal Academy on loan from the Hermitage in 2008. Diana Athill's rapture is not misplaced; this huge painting is one of the most dramatic and visually powerful modernist works, as well as one of the simplest. It is widely seen as Matisse's response to Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, another big, bold 'statement' painting, and one that seemed to change - and challenge - everything. However, Matisse's Dance could hardly be more different: whereas Les Demoiselles is all jagged confrontation, Dance is all self-absorbed ecstasy - all dance indeed.

The dancers are barely individualised, faceless (all but one) and minimally notated, and the Arcadian setting in which they dance is reduced to pure colour: blue sky, green earth. The dancers too are pure colour - a fiercely vital red. It is the interplay of those red bodies that gives the painting its kinetic life; these are bodies in motion, caught in the frenzy of the dance. The figure on the left is key to the composition - the perfect turning curve of his body at once anchors and drives the movements of the other dancers, whose wild poses are more pagan than classical.

The roots of Matisse's Dance can be traced in classical art, in Botticelli and Poussin, Turner, even Blake - but it is defiantly modern, defiantly itself. It still retains its power - and its mystery. Like all pictures of dance, it's an attempt to paint the unpaintable, but this painting that doesn't engage with, doesn't seem to need, the viewer is uniquely elusive. It is a picture in which you can only immerse yourself receptively, listening to its silent music - as Diana Athill, in her wheelchair, did with such relish.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

What a bradford barnstorming week of dance, two interesting posts from Nige and an excellent documentary on Pina Bausch, the Ruhr's highly regarded hoofer, set in, of all places, Düsseldorf airport's light railway and Essen's marvellous Zollverein deep mine's Bauhausian pit head office complex, chuck in our dearly beloved state broadcaster's attempt to out-Holywood Hollywood and dance is the new black.

ReplyDeleteThe new black indeed Malty - and the boys are wearing it: they're outnumbering girls in the ballet colleges now. Unfortunately though they don't have the muscle to compete with the Acostas of this world. As the man said, 'Ardest game in the world, the ballet game...

ReplyDelete