I've just finished reading Beware Of Pity, published in 1939 and the only full-scale novel of Stefan Zweig, who I gather is best known for his biographies, histories and shorter fictions - inasmuch as he's known at all in this country. I hadn't read him before, despite being very partial to the work of Joseph Roth - another Jewish writer (though a much less couth one) from the golden dying days of the Austro-Hungarian empire whose later life was dominated and finally undone by the rise of Nazism. Beware Of Pity is an extraordinary feat of storytelling - Zweig certainly has the gift of buttonholing the reader and keeping him turning the pages - which begins conventionally enough (in a manner reminiscent of Somerset Maugham), and indeed looks for a while as if it might be no more than an overgrown short story. Zweig's style is spacious and inclusive, but it gradually becomes apparent (or so it seemed to me) that this amplitude is essential, that Zweig is proceeding cumulatively, building up the milieu - life in the Imperial Army immediately before the Great War - in detail, with its codes, conventions and rituals, embedding his protagonist firmly in it, then inexorably building up the increasingly impossible, inescapable situation he finds himself in. He is a young second lieutenant who, at a dance at a nearby landowner's house, asks his host's young daughter for a dance, not realising that she is crippled and unable to walk. A minor incident, but her reaction is so extreme that the young man feels obliged to make good his error and assuage his guilt. Soon he is a regular visitor at the house, welcomed and made much of. He has succumbed to pity, and everything that follows springs from this fatal indulgence - defined by a character in the book as 'really no more than the heart's impatience to be rid as quickly as possible of the painful emotion aroused by the sight of another's unhappiness' - in contrast to true compassion, 'which knows what it is about and is determined to hold out, in patience and forbearance, to the very limit of its strength and even beyond'. Our hero's pity certainly doesn't know what it is about, as he sleepwalks into a situation from which, finally, suicide seems the only honourable escape. There's something dreamlike (as well as somnambulistic) about the inevitability of what happens - and all the crucial scenes seem to take place at night, often very late (the characters scarcely seem to sleep - and their capacity for drink, by the way, is phenomenal). All the time, Zweig is expertly guiding his protagonist into a moral catastrophe that will trap him like a fly in a fly bottle. Each eye-opening realisation of what is happening to him comes too late for him to escape it. The action speeds up, the tension rises, the crisis looms... This is a gripping, indeed a shaking novel, one that grabs you and won't let go. I must read more of him. Meanwhile, here's Clive James on Zweig the humanist and man of letters.

I've just finished reading Beware Of Pity, published in 1939 and the only full-scale novel of Stefan Zweig, who I gather is best known for his biographies, histories and shorter fictions - inasmuch as he's known at all in this country. I hadn't read him before, despite being very partial to the work of Joseph Roth - another Jewish writer (though a much less couth one) from the golden dying days of the Austro-Hungarian empire whose later life was dominated and finally undone by the rise of Nazism. Beware Of Pity is an extraordinary feat of storytelling - Zweig certainly has the gift of buttonholing the reader and keeping him turning the pages - which begins conventionally enough (in a manner reminiscent of Somerset Maugham), and indeed looks for a while as if it might be no more than an overgrown short story. Zweig's style is spacious and inclusive, but it gradually becomes apparent (or so it seemed to me) that this amplitude is essential, that Zweig is proceeding cumulatively, building up the milieu - life in the Imperial Army immediately before the Great War - in detail, with its codes, conventions and rituals, embedding his protagonist firmly in it, then inexorably building up the increasingly impossible, inescapable situation he finds himself in. He is a young second lieutenant who, at a dance at a nearby landowner's house, asks his host's young daughter for a dance, not realising that she is crippled and unable to walk. A minor incident, but her reaction is so extreme that the young man feels obliged to make good his error and assuage his guilt. Soon he is a regular visitor at the house, welcomed and made much of. He has succumbed to pity, and everything that follows springs from this fatal indulgence - defined by a character in the book as 'really no more than the heart's impatience to be rid as quickly as possible of the painful emotion aroused by the sight of another's unhappiness' - in contrast to true compassion, 'which knows what it is about and is determined to hold out, in patience and forbearance, to the very limit of its strength and even beyond'. Our hero's pity certainly doesn't know what it is about, as he sleepwalks into a situation from which, finally, suicide seems the only honourable escape. There's something dreamlike (as well as somnambulistic) about the inevitability of what happens - and all the crucial scenes seem to take place at night, often very late (the characters scarcely seem to sleep - and their capacity for drink, by the way, is phenomenal). All the time, Zweig is expertly guiding his protagonist into a moral catastrophe that will trap him like a fly in a fly bottle. Each eye-opening realisation of what is happening to him comes too late for him to escape it. The action speeds up, the tension rises, the crisis looms... This is a gripping, indeed a shaking novel, one that grabs you and won't let go. I must read more of him. Meanwhile, here's Clive James on Zweig the humanist and man of letters.

Wednesday, 7 April 2010

Beware of Pity

I've just finished reading Beware Of Pity, published in 1939 and the only full-scale novel of Stefan Zweig, who I gather is best known for his biographies, histories and shorter fictions - inasmuch as he's known at all in this country. I hadn't read him before, despite being very partial to the work of Joseph Roth - another Jewish writer (though a much less couth one) from the golden dying days of the Austro-Hungarian empire whose later life was dominated and finally undone by the rise of Nazism. Beware Of Pity is an extraordinary feat of storytelling - Zweig certainly has the gift of buttonholing the reader and keeping him turning the pages - which begins conventionally enough (in a manner reminiscent of Somerset Maugham), and indeed looks for a while as if it might be no more than an overgrown short story. Zweig's style is spacious and inclusive, but it gradually becomes apparent (or so it seemed to me) that this amplitude is essential, that Zweig is proceeding cumulatively, building up the milieu - life in the Imperial Army immediately before the Great War - in detail, with its codes, conventions and rituals, embedding his protagonist firmly in it, then inexorably building up the increasingly impossible, inescapable situation he finds himself in. He is a young second lieutenant who, at a dance at a nearby landowner's house, asks his host's young daughter for a dance, not realising that she is crippled and unable to walk. A minor incident, but her reaction is so extreme that the young man feels obliged to make good his error and assuage his guilt. Soon he is a regular visitor at the house, welcomed and made much of. He has succumbed to pity, and everything that follows springs from this fatal indulgence - defined by a character in the book as 'really no more than the heart's impatience to be rid as quickly as possible of the painful emotion aroused by the sight of another's unhappiness' - in contrast to true compassion, 'which knows what it is about and is determined to hold out, in patience and forbearance, to the very limit of its strength and even beyond'. Our hero's pity certainly doesn't know what it is about, as he sleepwalks into a situation from which, finally, suicide seems the only honourable escape. There's something dreamlike (as well as somnambulistic) about the inevitability of what happens - and all the crucial scenes seem to take place at night, often very late (the characters scarcely seem to sleep - and their capacity for drink, by the way, is phenomenal). All the time, Zweig is expertly guiding his protagonist into a moral catastrophe that will trap him like a fly in a fly bottle. Each eye-opening realisation of what is happening to him comes too late for him to escape it. The action speeds up, the tension rises, the crisis looms... This is a gripping, indeed a shaking novel, one that grabs you and won't let go. I must read more of him. Meanwhile, here's Clive James on Zweig the humanist and man of letters.

I've just finished reading Beware Of Pity, published in 1939 and the only full-scale novel of Stefan Zweig, who I gather is best known for his biographies, histories and shorter fictions - inasmuch as he's known at all in this country. I hadn't read him before, despite being very partial to the work of Joseph Roth - another Jewish writer (though a much less couth one) from the golden dying days of the Austro-Hungarian empire whose later life was dominated and finally undone by the rise of Nazism. Beware Of Pity is an extraordinary feat of storytelling - Zweig certainly has the gift of buttonholing the reader and keeping him turning the pages - which begins conventionally enough (in a manner reminiscent of Somerset Maugham), and indeed looks for a while as if it might be no more than an overgrown short story. Zweig's style is spacious and inclusive, but it gradually becomes apparent (or so it seemed to me) that this amplitude is essential, that Zweig is proceeding cumulatively, building up the milieu - life in the Imperial Army immediately before the Great War - in detail, with its codes, conventions and rituals, embedding his protagonist firmly in it, then inexorably building up the increasingly impossible, inescapable situation he finds himself in. He is a young second lieutenant who, at a dance at a nearby landowner's house, asks his host's young daughter for a dance, not realising that she is crippled and unable to walk. A minor incident, but her reaction is so extreme that the young man feels obliged to make good his error and assuage his guilt. Soon he is a regular visitor at the house, welcomed and made much of. He has succumbed to pity, and everything that follows springs from this fatal indulgence - defined by a character in the book as 'really no more than the heart's impatience to be rid as quickly as possible of the painful emotion aroused by the sight of another's unhappiness' - in contrast to true compassion, 'which knows what it is about and is determined to hold out, in patience and forbearance, to the very limit of its strength and even beyond'. Our hero's pity certainly doesn't know what it is about, as he sleepwalks into a situation from which, finally, suicide seems the only honourable escape. There's something dreamlike (as well as somnambulistic) about the inevitability of what happens - and all the crucial scenes seem to take place at night, often very late (the characters scarcely seem to sleep - and their capacity for drink, by the way, is phenomenal). All the time, Zweig is expertly guiding his protagonist into a moral catastrophe that will trap him like a fly in a fly bottle. Each eye-opening realisation of what is happening to him comes too late for him to escape it. The action speeds up, the tension rises, the crisis looms... This is a gripping, indeed a shaking novel, one that grabs you and won't let go. I must read more of him. Meanwhile, here's Clive James on Zweig the humanist and man of letters.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

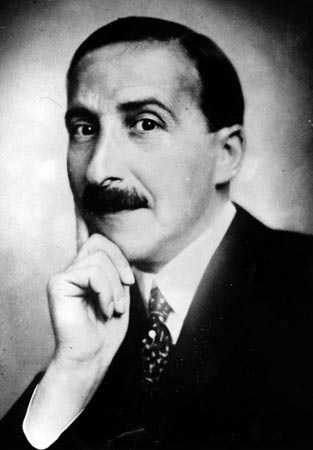

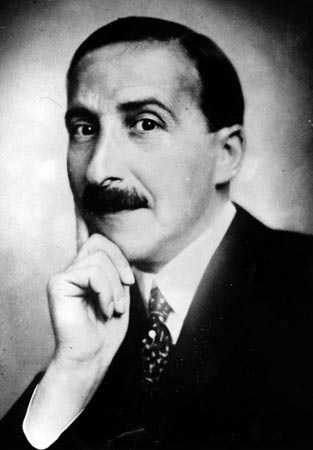

By the way, the picture's Zweig, not me. I like the look of him.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteWell, clearly: he's not wearing a cravat.

ReplyDeleteI gain the impression that you prefer it to The Radetzky March. Is that right and is it just because of Zweig's greater couthness? I can't recall that Roth was uncouth; not in comparison to most novelists of the C20th.

8 April 2010 08:39

Delete

O no Recusant - I think The Radetzky March is a great novel, one that I'd happily read again and again - I don't feel that about Beware of Pity.

ReplyDeleteIf you get a chance to see Collaboration by Ronald Harwood, it is about Zweig and Richard Strauss and is very moving - at least it was in the production at Chichester last summer.

ReplyDelete