To mark the 400th anniversary of Andrew Marvell's birth – and the suddenly garden-friendly weather – what more appropriate than one of his greatest poems, The Garden? (See also today's Anecdotal Evidence.)

Wednesday, 31 March 2021

The Garden

Monday, 29 March 2021

Freedom Day

Here's a suitable image for 'freedom day', showing what it might have looked like in more decorous, better dressed times – Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, surely one of the great paintings of the 19th century. Seurat died on this day 130 years ago, at the age of just 31. What wonders might he have achieved had he lived longer?

For myself, I have been out and about most of the day, enjoying the sunshine and the (you guessed!) butterflies – Peacocks and Brimstones were out in numbers, and I saw my first Comma and Tortoiseshell of the year. The butterfly season is under way – let's hope the same applies to the journey back to normal human life.

Sunday, 28 March 2021

Anarchy in Suburbia?

Much excited talk on the radio this morning about the heady new freedoms that are to be granted to us by the Committee of Public Safety from tomorrow – outdoor gatherings (including in private gardens!) of up to 6 people or 2 households, outdoor sports facilities reopening, the 'stay at home' rule withdrawn.

Hmm. I don't know if I live in a particularly anarchic corner of suburbia, but when I'm out and about, these rules seem to have been more honoured in the breach than the observance (a cliché, but with real meaning – some rules are more honourably breached than observed. As Junius put it, 'The subject who is truly loyal to the Chief Magistrate will neither advise nor submit to arbitrary measures.'). I suspect that tomorrow things will look much as they have done for several weeks around here.

This morning I noticed that several posters along these lines [below] have gone up in the neighbourhood – maybe this is indeed a particularly anarchic corner of suburbia...

Anyway, let's look forward to freedom and outdoor pleasures, as so beautifully evoked in Keats's sonnet (published in his Poems of 1817) –

'As one who, long in populous city pent,

Where houses thick and sewers annoy the air,

Forth issuing on a summer’s morn, to breathe

Among the villages and farms

The smell of grain, or tedded grass, or kine,

Or dairy, each rural sight, each rural sound...'

Friday, 26 March 2021

Corn-Fed Girls

Further to the previous post, the one and only Dave Lull has been at work looking for 'milk-fed girls' in Wodehouse and has drawn a blank – and if a blank is drawn by Dave Lull, a blank it is. It seems I misremembered, for what he did come up with was this passage from Carry On, Jeeves (1927) referring to 'largish, corn-fed girls'. It's a nice bit of vintage Wodehouse, so I pass it on in the interests of spreading some good cheer –

'That Aunt Dahlia had not exaggerated the perilous nature of the situation was made clear to me on the following afternoon. Jeeves and I drove down to Bleaching in the two-seater, and we were tooling along about half-way between the village and the Court when suddenly there appeared ahead of us a sea of dogs and in the middle of it young Tuppy frisking round one of those largish, corn-fed girls. He was bending towards her in a devout sort of way, and even at a considerable distance I could see that his ears were pink. His attitude, in short, was unmistakably that of man endeavouring to push a good thing along; and when I came closer and noted that the girl wore tailor-made tweeds and thick boots, I had no further doubts.'

Young Tuppy Glossop had a decidedly Betjemanian taste in girls.

Wednesday, 24 March 2021

Sporty Gels

On this day 100 years ago, the first Women's Olympiad got under way in the gardens of the Monte Carlo Casino. A hundred ladies from France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Norway and Switzerland took part in a range of running and jumping events, javelin and shot put. There were demonstration events too, including rhythmic gymnastics and, rather wonderfully, pushball, a variant of football in which a 50lb, six-foot-diameter ball is pushed by two teams towards each other's goals. The Olympiad sounds like a charming occasion, and the participants bore little resemblance to today's female athletes. They were fine, milk-fed girls*, decorously dressed, with full bosoms, sturdy legs and not a six-pack or a five o-clock shadow in sight. They were, indeed, the kind of sporty gels who appealed to Betjeman, who even wrote a poem titled 'The Olympic Girl' (not one of his better efforts) –

The sort of girl I like to see

Smiles down from her great height at me.

She stands in strong, athletic pose

And wrinkles her retroussé nose.

Is it distaste that makes her frown,

So furious and freckled, down

On an unhealthy worm like me?

Or am I what she likes to see?

I do not know, though much I care,

xxxxxxxx.....would I were

(Forgive me, shade of Rupert Brooke)

An object fit to claim her look.

Oh! would I were her racket press'd

With hard excitement to her breast

And swished into the sunlit air

Arm-high above her tousled hair,

And banged against the bounding ball

"Oh! Plung!" my tauten'd strings would call,

"Oh! Plung! my darling, break my strings

For you I will do brilliant things."

And when the match is over, I

Would flop beside you, hear you sigh;

And then with what supreme caress,

You'd tuck me up into my press.

Fair tigress of the tennis courts,

So short in sleeve and strong in shorts,

Little, alas, to you I mean,

For I am bald and old and green.

Tuesday, 23 March 2021

'A game of intricate enchantment and deception'

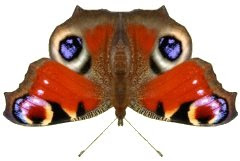

I have seen several Peacock butterflies so far this year (along with rather more Brimstones and one Comma). They are always a delight to see, and they also offer food for thought – why such a spectacular, hyperreal simulation of four 'eyes'? Can it really be just a case of protective mimicry? Surely it goes way beyond any possible usefulness. And look what happens when you turn the Peacock upside down – suddenly it's an owl! This is surely not protective mimicry: apart from anything else, the butterfly's predators typically attack from behind rather than in front. Is a predator going to think, 'Aha, here's a nice juicy butterfly. I think I'll just take a look round the front and... Oh my Lord, it's not a butterfly – it's an owl! I'm off.'? Hardly likely.

As Nabokov wrote (in Speak, Memory) on the extraordinary exuberance of butterfly mimicry, 'nor could one appeal to the theory of "struggle for life" when a protective device was carried to the point of mimetic subtlety, exuberance, and luxury far in excess of a predator's power of appreciation. I discovered in nature the non-utilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.'

Monday, 22 March 2021

They Might Be Related

Earlier today, for some reason, I was looking online for a painting by John Linnell. In the course of my search, I discovered that another, later John Linnell was and is half of the creative core of They Might Be Giants (with John Flansburgh). Naturally this chance discovery led me to play again that fine song Birdhouse in Your Soul – which I am now putting up here too, to bring a little good cheer to a locked-down nation. Enjoy...

Sunday, 21 March 2021

A Musical Centenary

Today is the centenary of the birth of the Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux, one of the 20th century's best. I have his classic set of Bach's partitas and sonatas, and was pleased to discover that a sample of Grumiaux's Bach found its way on to the Voyager Golden Record, that extraordinary disc that was launched into space in 1977 to give any receptive extraterrestrials an idea of what we humans are like. The Voyager will pass within 1.6 light years of the star Gliese 445 in 40,000 years or so – exciting times! Here, from the Golden Record, is Grumiaux playing the Gavotte en Rondeaux from Bach's Partita number 3 –

Lately I've been enjoying some of the Budapest String Quarter's recordings of Beethoven, and was again pleased to discover that they also are represented on the Golden Record, playing the glorious Cavatina from the B flat Quartet – which Beethoven himself thought was the most beautiful melody he ever wrote. Here it is – simply sublime music...

Friday, 19 March 2021

Home-Pain

Talking of nostalgia, it's a feeling I'm getting all too much of when I look back over recent times as recorded in my blog. The root meaning of nostalgia is home-pain, i.e. homesickness (something Odysseus's men, for all their machismo, were very prone to, I seem to recall). The home I feel pain for is the world I felt at home in, the one we all took for granted and thought would just carry on, pretty much unchanged – and then it was lost in the great convulsion of the Covid response. It was normal human life, with all its little social amenities – and I miss it and wonder when, or even if, it's going to come back.

A year ago at this time, Mrs N and I were seizing the chance to dine out on the final evening before Lockdown 1.0. It was to be a long while till either of us saw the inside of a restaurant again.

Two years ago, the world still had nearly a year of normal to go, and I was out and about as usual, taking in, among other things, a fine exhibition at the Pallant Gallery in Chichester (ah, the lost joy of wandering around a gallery, maskless and unimpeded). On that day I also wandered at liberty around the cathedral (another joy largely lost as the Church of England withdraws from the world to gaze into its 'institutionally racist' navel), and a couple of days later I was taking a look around Soane's Pitzhanger Manor in Ealing – what a mad whirl it seems from here...

Three years ago, I was enjoying a walk on and under the Sussex downs, in Gill Country (walking with my walker friends is another pleasure lost since last summer). And four years ago – ah, four years ago, I was In Deepest England (well, the Nottinghamshire Wolds), in those happy days when I was touring the obscure monuments of Platonic England for the purposes of writing this book. Had I been trying to write it now, I would have had to give up months ago – as, indeed, I have had to give up researching my next projected book. At least I was able to write my little butterfly book in the interim. I'll let you know when and if that one sees the light of day.

Wednesday, 17 March 2021

Justice's Nostalgia

Well, those two Donald Justice poems seemed to go down very well, so let's have a couple more. Justice is one of the great poets of nostalgia, which is perhaps why his works seem so resonant now, in this strange time when we are all painfully nostalgic for those simple amenities of life that we used to take for granted: dropping in to the pub, sitting in cafés, eating in restaurants, weekends away, holidays, open churches, going where we wanted with whomever we wanted to go with... Justice's nostalgia, particularly for his Miami boyhood, is a potent force in his work, setting the happy-sad emotional climate of many of his best poems. Sometimes it is more sad than happy, as in this late poem, titled 'Sadness' (though there is happiness there as well, as in stanza 5) –

A tall loudspeaker is announcing prizes;

Another, by the lake, the times of cruises.

Childhood, once vast with terrors and surprises,

Is fading to a landscape deep with distance—

And always the sad piano in the distance,

(O indecipherable blurred harmonies)

Or some far horn repeating over water

Its high lost note, cut loose from all harmonies.

At such times, wakeful, a child will dream the world,

And this is the world we run to from the world.

Or the two worlds come together and are one

On dark, sweet afternoons of storm and of rain,

And stereopticons brought out and dusted,

Stacks of old Geographics, or, through the rain,

A mad wet dash to the local movie palace

And the shriek, perhaps, of Kane’s white cockatoo.

(Would this have been summer, 1942?)

By June the city always seems neurotic.

But lakes are good all summer for reflection,

And ours is famed among painters for its blues,

Yet not entirely sad, upon reflection.

Why sad at all? Is their wish so unique—

To anthropomorphise the inanimate

With a love that masquerades as pure technique?

O art and the child were innocent together!

But landscapes grow abstract, like ageing parents.

Soon now the war will shutter the grand hotels,

And we, when we come back, will come as parents.

There are no lanterns now strung between pines—

Only, like history, the stark bare northern pines.

And after a time the lakefront disappears

Into the stubborn verses of its exiles

Or a few gifted sketches of old piers.

It rains perhaps on the other side of the heart;

Then we remember, whether we would or no.

—Nostalgia comes with the smell of rain, you know.

Monday, 15 March 2021

And...

I've just been revisiting this Donald Justice poem – his last – and finding it even more beautiful than I remembered, so...

1

There is a gold light in certain old paintings

That represents a diffusion of sunlight.

It is like happiness, when we are happy.

It comes from everywhere and nowhere at once, this light,

And the poor soldiers sprawled at the foot of the cross

Share in its charity equally with the cross.

2

Orpheus hesitated beside the black river.

With so much to look forward to he looked back.

We think he sang then, but the song is lost.

At least he had seen once more the beloved back.

I say the song went this way: O prolong

Now the sorrow if that is all there is to prolong.

3

The world is very dusty, uncle. Let us work.

One day the sickness shall pass from the earth for good.

The orchard will bloom; someone will play the guitar.

Our work will be seen as strong and clean and good.

And all that we suffered through having existed

Shall be forgotten as though it had never existed.

Dismal Reflections – and a Poem

This time last year there were long queues outside every supermarket, and inside hordes of people – none wearing masks – fighting for the last toilet roll/ packet of pasta/rice/ bag of flour. To see those scenes now would be a shock, not least because we've become so inured to mask-wearing that even the mask-sceptics among us would find it odd. (Of course, back then the appalling WHO was advising strongly against face-coverings, and indeed any checks on incomers at airports.) After all these months, we are taking for granted a state of affairs that we could never even have contemplated before 2020 – a wholesale confiscation of basic liberties and rights, and the suspension of most of what makes life liveable and worth living, all in the name of Public Safety (shades of the revolutionaryTerror) and all on the basis of 'science' that was far from rock-solid. And now it seems normal. What has become of us? Even I am feeling my spirits sinking these days, as this drags on and on.

What is also striking about that peep into the past is how brief that period of consumer chaos was. Within a very short time, the supermarkets regained control, re-established supply lines and restored order. Their workers, along with the bin men, postal workers, delivery drivers, transport workers, small shopkeepers, cab drivers and all those doing the real and necessary work carried on without missing a beat – and with precious little thanks for their efforts. As someone has said, the Covid response proved to be a great opportunity for the managerial class to make their work-life balance more agreeable, while the 'little people' carried on toiling away, servicing their needs. And it's those 'little people' who will be paying the price for all this, overwhelmingly.

But enough of that. Here's a poem – we all need poems – by Donald Justice, which seems somehow relevant, and is anyway beautiful:

Bus Stop

Lights are burning

In quiet rooms

Where lives go on

Resembling ours.

The quiet lives

That follow us—

These lives we lead

But do not own—

Stand in the rain

So quietly

When we are gone,

So quietly . . .

And the last bus

Comes letting dark

Umbrellas out—

Black flowers, black flowers.

And lives go on.

And lives go on

Like sudden lights

At street corners

Or like the lights

In quiet rooms

Left on for hours,

Burning, burning.

Sunday, 14 March 2021

Cutter Sees the Future

Born on this day in 1837 was one of America's greatest librarians, Charles Ammi Cutter. He it was who created the first public card catalogue in America (at Harvard College), revolutionised the cataloguing of the Boston Athenaeum, and devised the pioneering Cutter Expansive Classification. His Wikipedia entry makes wonderfully restful reading.

The Cutter Expansive Classification ('an avant-garde and divergent system') had the great advantage that, unlike 'Melvil' Dewey's ultimately triumphant system, it could be easily adapted to the needs of different kinds and sizes of library. The basic version, for very small libraries, had just seven categories for non-fiction subjects, one of which (A) was for reference books. History was lumped together with Geography and Travels in F, whereas Social Sciences (H) and Biography (E) had each their own exclusive category. More problematically, Natural Sciences and Arts were crammed into one category (L) – that was surely never going to work. Even in more expanded versions of the classification, Science and Arts remain locked in an unlikely embrace... Wake up at the back there!

But here's a funny thing: in 1883 Cutter wrote a piece for the Library Journal in which he envisaged the Buffalo Public Library 100 years on, in 1983. 'The desks ,' he writes, 'had a little keyboard at each, connected by a wire. The reader had only to find the mark of his book in the catalog, touch a few lettered or numbered keys, and [the book] appeared after an astonishingly short interval.' Uncanny, eh?

Thursday, 11 March 2021

Larkin on Success/Failure

On this day in 1954, Philip Larkin wrote a curious poem about success, or rather failure –

Success Story

To fail (transitive and intransitive)

I find to mean be missing, disappoint,

Or not succeed in the attainment of

(As in this case, f. to do what I want);

They trace it from the Latin to deceive...

Yes. But it wasn't that I played unfair:

Under fourteen, I sent in six words

My Chief Ambition to the Editor

With the signed promise about afterwards –

I undertake rigidly to forswear

The diet of this world, all rich game

And fat forbidding fruit, go by the board

Until – But that until has never come,

And I am starving where I always did.

Time to fall to, I fancy: long past time.

The explanation goes like this, in daylight:

To be ambitious is to fall in love

With a particular life you haven't got

And (since love picks your opposite) won't achieve.

That's clear as day. But come back late at night,

You'll hear a curious counter-whispering:

Success, it says, you've scored a great success.

Your wish has flowered, you've dodged the dirty feeding,

Clean past it now at hardly any price –

Just some pretence about the other thing.

Those quintains are cunningly structured – ababa, but all in half-rhymes. The theme of success/failure was to be a persistent one in Larkin's mature verse (though not as persistent as death, of course) and his relationship to it/them was never straightforward. It started early: here is a sonnet written five years before 'Success Story', and already failure is there at the young poet's elbow –

To Failure

You do not come dramatically, with dragons

That rear up with my life between their paws

And dash me butchered down beside the wagons,

The horses panicking; nor as a clause

Clearly set out to warn what can be lost,

What out-of-pocket charges must be borne,

Expenses met; nor as a draughty ghost

That's seen, some mornings, running down a lawn.

It is these sunless afternoons, I find,

Instal you at my elbow like a bore.

The chestnut trees are caked with silence. I'm

Aware these days pass quicker than before,

Smell staler too. And once they fall behind,

They look like ruin. You have been here some time.

Wednesday, 10 March 2021

Human Wishes

I've just read Samuel Beckett's Human Wishes. This did not take long, as it's no more than a fragment of a projected play that never got written. It left me wishing there was more, much more...

Taking its title from The Vanity of Human Wishes, this was originally intended to be a drama about Dr Johnson's complicated relationship with Hester Thrale. Beckett made extensive notes for this, drawing on Mrs Thrale's recollections rather than Boswell's life of Johnson. However, he then changed course and started writing about life in the Johnson household, with its population of waifs and strays whom the good doctor had taken under his wing, including blind Mrs Williams, Mrs Desmoulins, Miss Carmichael and Dr Levett (an apothecary with a taste for drink). In Johnson's own words (writing to the Thrales), 'Williams hates everybody; Levett hates Desmoulins, and does not love Williams; Desmoulins hates them both; Poll (Miss Carmichael) loves none of them.' What better dramatic set-up could one hope for?

The surviving fragment features all of these, first the ladies chewing bits out of each other, and then – an incident: the return of Levett. After which it's back to the ladies. In this passage, it is easy to hear pre-echoes of the dramas that were to make Beckett's name two decades later (Human Wishes was written in 1937). As I said, I wish there was more...

Enter LEVETT, slightly, respectably, even reluctantly drunk, in great coat and hat, which he does not remove, carrying a small black bag. He advances unsteadily into the room & stands peering at the company. Ignored ostentatiously by Mrs D (knitting), Miss Carmichael (reading), Mrs W (meditating), he remains a little standing as though lost in thought, then suddenly emits a hiccup of such force that he is almost thrown off his feet. Startled from her knitting Mrs D, from her book Miss C, from her stage meditation Mrs W, survey him with indignation. L remains standing a little longer, absorbed & motionless, then on a wide tack returns cautiously to the door, which he does not close behind him. His unsteady footsteps are heard on the stairs. Between the three women exchange of looks. Gestures of disgust. Mouths opened and shut. Finally they resume their occupations.

Mrs W: Words fail us.

Mrs D: Now this is where a writer for the stage would have us speak, no doubt.

Mrs W: We would have to explain Levett.

Mrs D: To the public.

Mrs W: The ignorant public.

Mrs D: To the gallery.

Mrs W: To the pit.

Miss C: To the boxes.

Mrs W: Mr Murphy.

Mrs D: Mr Kelly.

Miss C: Mr Goldsmith.

Mrs D: Let us not speak unkindly of the departed.

Miss C: The departed?

Mrs D: Can you be unaware, Miss, that the dear doctor's [Goldsmith's] debt to nature –

Mrs W: Not a very large one.

Mrs D: That the dear doctor's debt to nature is discharged these seven years.

Mrs W: More.

Mrs D: Seven years today, Madam, almost to the hour, neither more nor less.

Miss C: His debt to nature?

Mrs W: She means the wretched man is dead.

Miss C: Dead!

Mrs W: Dead. D-E-A-D. Expired. Like the late Queen Anne and the Rev. Edward –

Miss C: Well I am heartily sorry indeed to hear that.

Mrs W: So was I, Miss, heartily sorry indeed to hear it, at the time, being of the opinion, as I still am, that before paying his debt to nature he might have paid his debt to me. Seven shillings and sixpence, extorted on the contemptible security of his Animated Nature. He asked for a guinea.

Mrs D: There are many, Madam, more sorely disappointed, willing to forget the frailties of a life long since transported to that undiscovered country from whose –

Mrs W (striking the floor with her stick). None of your Shakespeare to me, Madam. The fellow may be in Abraham's bosom for aught I know or care, I still say he ought to be in Newgate.

Mrs D (sighs and goes back to her knitting).

Mrs W: I am dead enough myself, I hope, not to feel any great respect for those that are so entirely.

Silence.

Monday, 8 March 2021

A Major Statue of Concern

I guess it had to happen: the statue of Philip Larkin, the well-known racist, that stands outside Hull's Paragon station, has turned up on a list of 'major statues of concern' compiled by Hull City Council in response to the Black Lives Matters vogue. He is in good company, as it seems Andrew Marvell is also on the list. Hey ho.

What's striking about the Larkin statue is that it's actually rather good, portraying the poet in motion and effectively capturing something of his character and energy. I can think of only one other modern sculpture of a poet that is as good (if not rather better), and that is John Betjeman on St Pancras station, holding on to his hat as he looks up at that wondrous roof. Like Larkin, he too is wearing an eloquent raincoat; these are conventionally dressed Englishmen, out and about in English weather, and both carrying bags. There is nothing heroic, or conventionally 'poetic', about either statue – which is as it should be.

Sunday, 7 March 2021

Fun with Ricks

It must be 20 years (exactly that if a Greek bank slip, used as a bookmark, is to be believed) since I read Christopher Ricks's Beckett's Dying Words. My memory being what it is, I could remember only that I enjoyed it at the time. And now I am enjoying it all over again, enjoying it hugely. Like Ricks's Keats and Embarrassment, Beckett's Dying Words is a reminder of how much sheer fun good, sharp, closely attentive literary criticism can be in the right hands. And, indirectly, it is a reminder of what a dismal, impoverished wasteland much of what passes today for literary criticism can be. In defence of Samuel Beckett's greatness, Ricks takes a swipe or two at some recent academic criticism of the late works –

'... his late fiction is often all-too-accommodatingly spoken of as if it were abstracted, not to death, but to that impercipient living death which constitutes one of the present fashions in literary studies: the flaccid assurance that everything is fictive and verbal, and that the real has finally been shown the door. Things shown the door have a way of coming back in through the window, and the insistent rhetoric of in fact is much deployed by those who deny the existence of facts, or who don the rubber gloves of inverted commas – 'the facts' – except when it is their own fact-finding that is promulgated.

Opposition to this glee at the irreal can fasten upon its self-contradiction (if all is fictive, against what does the fictive define itself?) and can diagnose galloping logomania. But it is art, not argumentation, which constitutes the best, the most enduring opposition to such airiness.'

Indeed it is, and to read Beckett's late fiction is to expose such talk for the inattentive, self-serving nonsense it is. Ricks comes up with a string of quotations that do just that, and demolishes more cases of what he rightly diagnoses as the critics' 'intellectual abdication masquerading as majesty'. Anatomising one such passage (from a volume called Beckett Translating / Translating Beckett), he writes:

'The tawdry casualness of phrasing ('undermining' is overdue for burial) fits happily with the philosophical presumption ('the referential function of language has been exposed as a sham') – and with the gaping holes in the argument ('oddly free'? 'by definition'?). It is wisely unfathomable what it could be to find language 'the source of its own meaning', but it can be understood all too clearly that the easy invoking of 'at least a linguistic significance' is merely the usual gesture. Meanwhile, reality – which is haled in as just another of those shams – is given the usual treatment, the infected hygiene, iatrogenic, of inverted commas: external 'reality'.

And all this is bent upon a writer who has shown us, through his words, how much more there is to his art than words, how unforgettable his apprehension of suffering, though not only of that...'

Ah, if only there were more critics like Ricks – but it seems wildly unlikely that today's academe, obsessed with political issues and Critical Theory, will produce them.

Friday, 5 March 2021

Nicholson's Olympic Gold

One day in 1928, the painter William Nicholson was astonished to learn that he had won a gold medal at the Amsterdam Olympics. Reasonably enough, he had assumed the Olympics were concerned only with sports, but in fact medals in the arts were still being awarded in 1928, and indeed the tradition lasted right through to the 1948 Olympiad. What Nicholson did not know was that his publishers, Heinemann, had submitted a 30-year-old illustrated book of his, An Almanac of Twelve Sports, to the Olympics awards committee. This was a collaboration with Rudyard Kipling, his friend and neighbour in Rottingdean at the time – woodcuts by Nicholson, rhymes by Kipling. Here is Kipling's contribution for June's sport – Cricket:

'Thank God who made the British Isles

And taught me how to play,

I do not worship crocodiles,

Or bow the knee to clay!

Give me a willow wand and I,

With hide and cork and twine,

From century to century

Will gambol round my Shrine.'

Hmm. I don't think he was really trying there.

Anyway, Nicholson was delighted with the unexpected Olympic news and flew out to Amsterdam with his wife, enjoying four days at the Games, hearing his name read out on the loudspeaker and seeing the Union flag duly flown. 'We had wonderful weather,' he recalled, 'and enjoyed it more than any adventure we ever had. The Olympic people were nice to us and we saw all the world jumping their horses over impossible things.

Wednesday, 3 March 2021

Searle

Having unaccountably missed last year's Ronald Searle centenary, I'll mark it today, a year late. Searle, one of the great draughtsmen of the 20th century, was born on this day in 1920, and died, after a very good innings, at the end of 2011. The huge success of St Trinian's has tended to overshadow his other work – which is a great shame, as the prolific Searle applied his art to a wide range of subjects – cats, wine, books, life as a Japanese PoW – and everything he drew is utterly distinctive and full of rare graphic vitality. For me, of course, his greatest creation (in collaboration with Geoffrey Willans, who wrote the words) was Nigel Molesworth, the Curse of St Custard's. That's him above, with a representative selection of headmasters. Floreat Molesworth! Floreat Sancto Crustare!

Monday, 1 March 2021

Newly Foxed

March already, and with the new month comes a new issue of that fine and handsome literary quarterly Slightly Foxed. It includes something by me on Julia Strachey (transcribed below), and much else, including an excellent piece by Charles Hebbert on the Hungarian writer Antal Szerb, whose name might be familiar to readers of this blog, and another by Roger Hudson on John Byng's extraordinary diaries of his travels in England and Wales towards the end of the 18th century. Highly recommended, as ever.

‘A Kind of Cosmic Refugee’

Julia Strachey was a writer of rare talent and originality who, in a lifetime of writing, managed to complete and publish only two novels and a number of sketches and short stories. I knew nothing of her until I happened to come across a Penguin reprint of those novels, Cheerful Weather for the Wedding and An Integrated Man. I was immediately bowled over by their brilliance and originality, and was surprised to discover that, in effect, they are all there is. What stopped this gifted writer from finishing and publishing more?

It’s not that her work wasn’t in demand. When Cheerful Weather for the Wedding was published in 1932, it met with a very warm reception. The literary editor of The New Yorker was so impressed that he wrote to Julia and offered to publish anything she cared to send him. Her response was to send nothing for a quarter of a century, until in 1958 she obliged with a sketch, which was duly published – but not until Julia had fought at length, and successfully, to have every single editorial alteration to her piece reversed. Clearly this was not a woman with a strong sense of how to build a literary career.

It isn’t hard to see why Cheerful Weather for the Wedding so impressed its early readers. A cool, darkly comic account of an upper-middle-class wedding day in Dorset, it is brisk, deftly managed, sharply observed and crisply written, without a word wasted. But, more than that, there is something in the tone of it that is quite unique – something ‘airy and translucent’, as one critic put it. Strachey herself said, rather cryptically, that her aim was to convey a ‘phosphorescent’ impression, and there is a strange kind of luminosity about some descriptive passages, in which the author focuses her attention so fixedly on something that it seems to develop a faintly unearthly glow. Here she is on a pot of ferns:

‘The transparent ferns that stood massed in the window showed up very brightly, and looked fearful. They seemed to have come alive, so to speak. They looked to have just that moment reared up their long backs, arched their jagged and serrated bodies menacingly, twisted and knotted themselves tightly about each other, and darted out long forked and ribboning tongues from one to the other; and all as if under some terrible compulsion … they brought to mind travellers’ descriptions of the jungles in the Congo – of the silent struggle and strangulation that vegetable life there consists in.’

Strachey writes as if seeing those ferns for the first time, and her gaze is intense and appalled; she senses the menace lurking in the everyday objects that mass around us.

The dominant figure in Cheerful Weather is not the reluctant bride, who is quietly getting drunk – or her rejected suitor, who is rather more noisily getting drunk – but Mrs Thatcham, the bride’s mother, a human whirlwind who is typically to be found ‘rushing around the room on tiny feet, snapping off dead daffodil heads from the vases, pulling back window curtains, or pulling them forward, scratching on the carpet with the toe of her tiny shoe where a stain showed up. All this with a sharp anxiety on her face as usual, – as though she had inadvertently swallowed a packet of live bumble-bees and was now beginning to feel them stirring about inside her.’ Her constant refrain is ‘I simply cannot understand it!’, applied to anything that fails to conform to her view of how things should be.

There is another presence in the story, almost as strong as the human characters, and that is the brisk and blowy spring weather – the ‘cheerful weather’ (Mrs Thatcham’s phrase) of the title. And weather – in this case the ever changing weather of an English summer – is an equally strong presence in the second of Strachey’s novels, An Integrated Man, published (as The Man on the Pier) nearly 20 years after the first, in 1951. In this considerably longer work, events unfold over the length of a summer in the Thirties in a large country cottage, where a group of friends have gathered to talk, walk, eat and pass the time agreeably, while getting on with a little work. The ‘integrated man’ of the title is Ned Moon, who, in the very first paragraph, declares that ‘Everything in my life is well ordered and serene … My days are spent unharassed by pressures that torture and distort. At the age of forty-one, I’m bound to admit that I have become that fabulous beast, an “integrated man”!’ If ever a man were riding for a fall, it is Ned Moon…

As in Cheerful Weather, Strachey’s descriptive writing is highly distinctive, and summer in the country gives it plenty of scope:

‘At ten minutes to one the postman had appeared ... And certain cows, those that had lost their calves, on perceiving his red bicycle from afar, charged joyfully across the field in a bunch, imagining he was bringing back to them their stolen children. When they had realised their mistake, they had stood and trumpeted shrilly as usual for half an hour.

Then luncheon – and a massed rendezvous of flies!

... After lunch the cows had suddenly begun to bellow again. The flies, however, had dropped off to sleep.'

And here, later, are the flies again:

'All of a sudden the flies on the window-pane woke up and started to rage together with a venomous zizzing. One amongst them began to boom deafeningly and to throw its scaly body repeatedly against the glass. Others, too, began to boom in the same echoing manner, and soon all of them together were hurling their scaly bodies against the pane. One could imagine that packets of tintacks were being showered again and again at the glass.'

This high-strung, high-pitched style injects tension into what might otherwise seem placid and uneventful scenes (and An Integrated Man does get off to a slow start), but it comes fully into its own as Ned finally succumbs to the erotic fixation that is to prove his undoing. An Integrated Man is an extraordinarily frank and convincing account of the power of lust – and, in the end, the whole action turns on one sudden moment of recognition, conveyed in one startlingly raw paragraph. Impossible to say more of that without giving the plot away, but the climactic scene is a quite unforgettable piece of writing.

Both Julia Strachey’s novels were in danger of being forgotten altogether when, very enterprisingly, Penguin republished them both in one volume in 1978, introducing them to a whole new readership. Cheerful Weather was also reissued by Persephone Books as recently as 2009. In between, in 1983, came an illuminating volume mixing autobiography and biography – Julia: A Portrait of Julia Strachey by Herself and Frances Partridge. A friend of Julia’s since childhood, Frances Partridge had inherited her dauntingly voluminous and chaotic papers, including her autobiographical writings. These fragments of memoir – which, typically, had never been organised into a finished book – are vivid and revealing, and include some of her best writing. Merging these with letters, diary entries and her own memories of Julia, Frances Partridge creates a compelling portrait of her friend, and one that goes a long way to explaining the peculiarities of her literary career.

A strikingly beautiful woman, Julia was also ‘striking in her charm, her unhappiness and her formidable gifts’. And she was funny, spirited, exasperating and, despite everything, lovable. That striking unhappiness, though, is the key, and its roots lay deep. Her autobiographical writings begin with a rapturous, brightly coloured account of her childhood years in India, where her father, Oliver (elder brother of Lytton Strachey), was a senior civil servant. Her mother, Ruby, was young, beautiful and affectionate, and Julia was passionately in love with her. But this Indian paradise was lost with brutal abruptness when, at the age of six, with no word of explanation, Julia was sent with her mother to Italy, then on, with only a nursemaid, to the gloomy London house of a distant Strachey relation, where she was placed in the care of a fire-breathing elderly Scottish nanny. Both her parents had effectively washed their hands of her. This was the first, and hardest, betrayal of her life. She saw it as an expulsion from Paradise, and proof that there was something about her that meant that no one could truly love her.

This impression was confirmed when she was sent to live with the formidable Alys Pearsall Smith (‘Aunt Loo’) and her brother, the then revered aphorist Logan, whose sparkling wit was shadowed by crushing (and, to a child, terrifying) depressions. This ménage, in which the two adult principals cordially loathed each other, is brilliantly, and often very comically, described by Julia. But then comes the terrible moment when Aunt Loo inadvertently, but shatteringly, confirms Julia’s own opinion of her unlovableness. After this second betrayal, Julia sees herself as ‘just a dismal, moth-eaten, seedy kind of freak’, ‘an alien – a kind of cosmic refugee, an unwanted changeling from another planet’.

Considering the emotional legacy that she carried forward from her childhood, it is perhaps a wonder that Julia managed to make as good a life for herself as she did, rackety, unsettled and ill-organised though it often was (two failed marriages, fatal attraction to much younger men, amphetamine addiction). To an extent, she was her own worst enemy, constantly inventing reasons for her failure to apply herself systematically to her craft, complaining of imaginary impediments, spending hours ‘cogitating’ (often lying in bed, with the covers drawn up to her nose) instead of actually writing. But, to become a writer at all, she had to overcome not only her emotional problems but also a crippling dual legacy of Strachey perfectionism – the Stracheys had to be best at everything – and, from the Pearsall Smiths, intense self-criticism. We should be glad that, in all the circumstance, she managed to complete those two wonderful little novels by which she will surely be remembered.