I'm off to New Zealand tomorrow to spend a few weeks with daughter, son-in-law and grandsons in the fine city of Wellington. There will be occasional (or perhaps more frequent) dispatches.

As it will be, by the calendar, 2018 when we arrive, I'll seize the moment and wish all who browse here an early Happy New Year.

Thursday 28 December 2017

Wednesday 27 December 2017

Scotty

Let's liven up this grey post-Christmas, pre-New Year day by celebrating the birthday of Winfield Scott Moore III, better known as Scotty Moore, who was born on this day in 1931 (and died last year). As Elvis Presley's guitarist in the early days, Scotty was in at the birth of rock and roll and, with his power chords and urgent, gutsy picking style, he effectively created the sound of rock guitar. Sadly, as Elvis's career developed and he fell under the influence of Colonel Tom Parker, his original band tended to get sidelined, and they eventually went their separate ways.

Scotty was an inspiration to many young guitarists, including Jeff Beck, George Harrison and Keith Richards, and he remained a rightly revered guitar hero. When Keef first heard Heartbreak Hotel, it was a revelation: 'All I wanted to do in the world was to be able to play and sound like that. Everyone else wanted to be Elvis. I wanted to be Scotty.' Richards claimed that he could never quite work out how to play Moore's stop-time break and figure on I'm Left, You're Right, She's Gone. Let's spin that platter...

Scotty was an inspiration to many young guitarists, including Jeff Beck, George Harrison and Keith Richards, and he remained a rightly revered guitar hero. When Keef first heard Heartbreak Hotel, it was a revelation: 'All I wanted to do in the world was to be able to play and sound like that. Everyone else wanted to be Elvis. I wanted to be Scotty.' Richards claimed that he could never quite work out how to play Moore's stop-time break and figure on I'm Left, You're Right, She's Gone. Let's spin that platter...

Monday 25 December 2017

Sunday 24 December 2017

'She was ever, indeed, the most telephonic of her sex...'

I was reading, just now, Henry James's The Jolly Corner – a suitably creepy story for Christmastime – when it occurred to me that there was something more obviously like a Christmas story by Henry James, The Mote in the Middle Distance. This one, however, wasn't written by him but by Max Beerbohm, as one of the brilliant collection of parodies of his contemporaries 'gathered' by The Incomparable Max as A Christmas Garland. Here, for a little seasonal entertainment, is The Mote in the Middle Distance. Enjoy...

It was with the sense of a, for him, very memorable something that he peered now into the immediate future, and tried, not without compunction, to take that period up where he had, prospectively, left it. But just where the deuce had he left it? The consciousness of dubiety was, for our friend, not, this morning, quite yet clean-cut enough to outline the figures on what she had called his "horizon," between which and himself the twilight was indeed of a quality somewhat intimidating. He had run up, in the course of time, against a good number of "teasers;" and the function of teasing them back – of, as it were, giving them, every now and then, "what for" – was in him so much a habit that he would have been at a loss had there been, on the face of it, nothing to lose. Oh, he always had offered rewards, of course – had ever so liberally pasted the windows of his soul with staring appeals, minute descriptions, promises that knew no bounds. But the actual recovery of the article – the business of drawing and crossing the cheque, blotched though this were with tears of joy – had blankly appeared to him rather in the light of a sacrilege, casting, he sometimes felt, a palpable chill on the fervour of the next quest. It was just this fervour that was threatened as, raising himself on his elbow, he stared at the foot of his bed. That his eyes refused to rest there for more than the fraction of an instant, may be taken – was, even then, taken by Keith Tantalus – as a hint of his recollection that after all the phenomenon wasn't to be singular. Thus the exact repetition, at the foot of Eva's bed, of the shape pendulous at the foot of his was hardly enough to account for the fixity with which he envisaged it, and for which he was to find, some years later, a motive in the (as it turned out) hardly generous fear that Eva had already made the great investigation "on her own." Her very regular breathing presently reassured him that, if she had peeped into "her" stocking, she must have done so in sleep. Whether he should wake her now, or wait for their nurse to wake them both in due course, was a problem presently solved by a new development. It was plain that his sister was now watching him between her eyelashes. He had half expected that. She really was – he had often told her that she really was – magnificent; and her magnificence was never more obvious than in the pause that elapsed before she all of a sudden remarked "They so very indubitably are, you know!"

It occurred to him as befitting Eva's remoteness, which was a part of Eva's magnificence, that her voice emerged somewhat muffled by the bedclothes. She was ever, indeed, the most telephonic of her sex. In talking to Eva you always had, as it were, your lips to the receiver. If you didn't try to meet her fine eyes, it was that you simply couldn't hope to: there were too many dark, too many buzzing and bewildering and all frankly not negotiable leagues in between. Snatches of other voices seemed often to intertrude themselves in the parley; and your loyal effort not to overhear these was complicated by your fear of missing what Eva might be twittering. "Oh, you certainly haven't, my dear, the trick of propinquity!" was a thrust she had once parried by saying that, in that case, he hadn't – to which his unspoken rejoinder that she had caught her tone from the peevish young women at the Central seemed to him (if not perhaps in the last, certainly in the last but one, analysis) to lack finality. With Eva, he had found, it was always safest to "ring off." It was with a certain sense of his rashness in the matter, therefore, that he now, with an air of feverishly "holding the line," said "Oh, as to that!"

Had she, he presently asked himself, "rung off"? It was characteristic of our friend – was indeed "him all over" – that his fear of what she was going to say was as nothing to his fear of what she might be going to leave unsaid. He had, in his converse with her, been never so conscious as now of the intervening leagues; they had never so insistently beaten the drum of his ear; and he caught himself in the act of awfully computing, with a certain statistical passion, the distance between Rome and Boston. He has never been able to decide which of these points he was psychically the nearer to at the moment when Eva, replying "Well, one does, anyhow, leave a margin for the pretext, you know!" made him, for the first time in his life, wonder whether she were not more magnificent than even he had ever given her credit for being. Perhaps it was to test this theory, or perhaps merely to gain time, that he now raised himself to his knees, and, leaning with outstretched arm towards the foot of his bed, made as though to touch the stocking which Santa Claus had, overnight, left dangling there. His posture, as he stared obliquely at Eva, with a sort of beaming defiance, recalled to him something seen in an "illustration." This reminiscence, however – if such it was, save in the scarred, the poor dear old woebegone and so very beguilingly not refractive mirror of the moment – took a peculiar twist from Eva's behaviour. She had, with startling suddenness, sat bolt upright, and looked to him as if she were overhearing some tragedy at the other end of the wire, where, in the nature of things, she was unable to arrest it. The gaze she fixed on her extravagant kinsman was of a kind to make him wonder how he contrived to remain, as he beautifully did, rigid. His prop was possibly the reflection that flashed on him that, if she abounded in attenuations, well, hang it all, so did he! It was simply a difference of plane. Readjust the "values," as painters say, and there you were! He was to feel that he was only too crudely "there" when, leaning further forward, he laid a chubby forefinger on the stocking, causing that receptacle to rock ponderously to and fro. This effect was more expected than the tears which started to Eva's eyes, and the intensity with which "Don't you," she exclaimed, "see?"

"The mote in the middle distance?" he asked. "Did you ever, my dear, know me to see anything else? I tell you it blocks out everything. It's a cathedral, it's a herd of elephants, it's the whole habitable globe. Oh, it's, believe me, of an obsessiveness!" But his sense of the one thing it didn't block out from his purview enabled him to launch at Eva a speculation as to just how far Santa Claus had, for the particular occasion, gone. The gauge, for both of them, of this seasonable distance seemed almost blatantly suspended in the silhouettes of the two stockings. Over and above the basis of (presumably) sweetmeats in the toes and heels, certain extrusions stood for a very plenary fulfilment of desire. And, since Eva had set her heart on a doll of ample proportions and practicable eyelids – had asked that most admirable of her sex, their mother, for it with not less directness than he himself had put into his demand for a sword and helmet – her coyness now struck Keith as lying near to, at indeed a hardly measurable distance from, the border-line of his patience. If she didn't want the doll, why the deuce had she made such a point of getting it? He was perhaps on the verge of putting this question to her, when, waving her hand to include both stockings, she said "Of course, my dear, you do see. There they are, and you know I know you know we wouldn't, either of us, dip a finger into them." With a vibrancy of tone that seemed to bring her voice quite close to him, "One doesn't," she added, "violate the shrine – pick the pearl from the shell!"

Even had the answering question "Doesn't one just?" which for an instant hovered on the tip of his tongue, been uttered, it could not have obscured for Keith the change which her magnificence had wrought in him. Something, perhaps, of the bigotry of the convert was already discernible in the way that, averting his eyes, he said "One doesn't even peer." As to whether, in the years that have elapsed since he said this either of our friends (now adult) has, in fact, "peered," is a question which, whenever I call at the house, I am tempted to put to one or other of them. But any regret I may feel in my invariable failure to "come up to the scratch" of yielding to this temptation is balanced, for me, by my impression – my sometimes all but throned and anointed certainty – that the answer, if vouchsafed, would be in the negative.

It was with the sense of a, for him, very memorable something that he peered now into the immediate future, and tried, not without compunction, to take that period up where he had, prospectively, left it. But just where the deuce had he left it? The consciousness of dubiety was, for our friend, not, this morning, quite yet clean-cut enough to outline the figures on what she had called his "horizon," between which and himself the twilight was indeed of a quality somewhat intimidating. He had run up, in the course of time, against a good number of "teasers;" and the function of teasing them back – of, as it were, giving them, every now and then, "what for" – was in him so much a habit that he would have been at a loss had there been, on the face of it, nothing to lose. Oh, he always had offered rewards, of course – had ever so liberally pasted the windows of his soul with staring appeals, minute descriptions, promises that knew no bounds. But the actual recovery of the article – the business of drawing and crossing the cheque, blotched though this were with tears of joy – had blankly appeared to him rather in the light of a sacrilege, casting, he sometimes felt, a palpable chill on the fervour of the next quest. It was just this fervour that was threatened as, raising himself on his elbow, he stared at the foot of his bed. That his eyes refused to rest there for more than the fraction of an instant, may be taken – was, even then, taken by Keith Tantalus – as a hint of his recollection that after all the phenomenon wasn't to be singular. Thus the exact repetition, at the foot of Eva's bed, of the shape pendulous at the foot of his was hardly enough to account for the fixity with which he envisaged it, and for which he was to find, some years later, a motive in the (as it turned out) hardly generous fear that Eva had already made the great investigation "on her own." Her very regular breathing presently reassured him that, if she had peeped into "her" stocking, she must have done so in sleep. Whether he should wake her now, or wait for their nurse to wake them both in due course, was a problem presently solved by a new development. It was plain that his sister was now watching him between her eyelashes. He had half expected that. She really was – he had often told her that she really was – magnificent; and her magnificence was never more obvious than in the pause that elapsed before she all of a sudden remarked "They so very indubitably are, you know!"

It occurred to him as befitting Eva's remoteness, which was a part of Eva's magnificence, that her voice emerged somewhat muffled by the bedclothes. She was ever, indeed, the most telephonic of her sex. In talking to Eva you always had, as it were, your lips to the receiver. If you didn't try to meet her fine eyes, it was that you simply couldn't hope to: there were too many dark, too many buzzing and bewildering and all frankly not negotiable leagues in between. Snatches of other voices seemed often to intertrude themselves in the parley; and your loyal effort not to overhear these was complicated by your fear of missing what Eva might be twittering. "Oh, you certainly haven't, my dear, the trick of propinquity!" was a thrust she had once parried by saying that, in that case, he hadn't – to which his unspoken rejoinder that she had caught her tone from the peevish young women at the Central seemed to him (if not perhaps in the last, certainly in the last but one, analysis) to lack finality. With Eva, he had found, it was always safest to "ring off." It was with a certain sense of his rashness in the matter, therefore, that he now, with an air of feverishly "holding the line," said "Oh, as to that!"

Had she, he presently asked himself, "rung off"? It was characteristic of our friend – was indeed "him all over" – that his fear of what she was going to say was as nothing to his fear of what she might be going to leave unsaid. He had, in his converse with her, been never so conscious as now of the intervening leagues; they had never so insistently beaten the drum of his ear; and he caught himself in the act of awfully computing, with a certain statistical passion, the distance between Rome and Boston. He has never been able to decide which of these points he was psychically the nearer to at the moment when Eva, replying "Well, one does, anyhow, leave a margin for the pretext, you know!" made him, for the first time in his life, wonder whether she were not more magnificent than even he had ever given her credit for being. Perhaps it was to test this theory, or perhaps merely to gain time, that he now raised himself to his knees, and, leaning with outstretched arm towards the foot of his bed, made as though to touch the stocking which Santa Claus had, overnight, left dangling there. His posture, as he stared obliquely at Eva, with a sort of beaming defiance, recalled to him something seen in an "illustration." This reminiscence, however – if such it was, save in the scarred, the poor dear old woebegone and so very beguilingly not refractive mirror of the moment – took a peculiar twist from Eva's behaviour. She had, with startling suddenness, sat bolt upright, and looked to him as if she were overhearing some tragedy at the other end of the wire, where, in the nature of things, she was unable to arrest it. The gaze she fixed on her extravagant kinsman was of a kind to make him wonder how he contrived to remain, as he beautifully did, rigid. His prop was possibly the reflection that flashed on him that, if she abounded in attenuations, well, hang it all, so did he! It was simply a difference of plane. Readjust the "values," as painters say, and there you were! He was to feel that he was only too crudely "there" when, leaning further forward, he laid a chubby forefinger on the stocking, causing that receptacle to rock ponderously to and fro. This effect was more expected than the tears which started to Eva's eyes, and the intensity with which "Don't you," she exclaimed, "see?"

"The mote in the middle distance?" he asked. "Did you ever, my dear, know me to see anything else? I tell you it blocks out everything. It's a cathedral, it's a herd of elephants, it's the whole habitable globe. Oh, it's, believe me, of an obsessiveness!" But his sense of the one thing it didn't block out from his purview enabled him to launch at Eva a speculation as to just how far Santa Claus had, for the particular occasion, gone. The gauge, for both of them, of this seasonable distance seemed almost blatantly suspended in the silhouettes of the two stockings. Over and above the basis of (presumably) sweetmeats in the toes and heels, certain extrusions stood for a very plenary fulfilment of desire. And, since Eva had set her heart on a doll of ample proportions and practicable eyelids – had asked that most admirable of her sex, their mother, for it with not less directness than he himself had put into his demand for a sword and helmet – her coyness now struck Keith as lying near to, at indeed a hardly measurable distance from, the border-line of his patience. If she didn't want the doll, why the deuce had she made such a point of getting it? He was perhaps on the verge of putting this question to her, when, waving her hand to include both stockings, she said "Of course, my dear, you do see. There they are, and you know I know you know we wouldn't, either of us, dip a finger into them." With a vibrancy of tone that seemed to bring her voice quite close to him, "One doesn't," she added, "violate the shrine – pick the pearl from the shell!"

Even had the answering question "Doesn't one just?" which for an instant hovered on the tip of his tongue, been uttered, it could not have obscured for Keith the change which her magnificence had wrought in him. Something, perhaps, of the bigotry of the convert was already discernible in the way that, averting his eyes, he said "One doesn't even peer." As to whether, in the years that have elapsed since he said this either of our friends (now adult) has, in fact, "peered," is a question which, whenever I call at the house, I am tempted to put to one or other of them. But any regret I may feel in my invariable failure to "come up to the scratch" of yielding to this temptation is balanced, for me, by my impression – my sometimes all but throned and anointed certainty – that the answer, if vouchsafed, would be in the negative.

Saturday 23 December 2017

The Pattern of Friendship

The other day, in Sheffield, I finally caught up with the Ravilious & Co exhibition I'd somehow failed to see when it was at the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne all through the summer. Now it's at Sheffield's excellent Millennium Gallery (free entry, what's more) and I'm delighted I've finally seen it.

It's a big exhibition, but with none of the oppressive feel of a blockbuster. There's such a rich variety of material – paintings and drawings, prints of all kinds, textiles, illustrated books, wallpapers, posters, marbled papers – and most of what is on show is so full of energy, humour and good cheer that it can only lift the spirits. The mood is only broken by the late watercolours painted by Ravilious when he was at sea as a war artist (before he disappeared on a flight over Iceland); these remarkable paintings convey a quite unexpected sense of mental turmoil and impending tragedy.

But this exhibition is about much more than Ravilious. It explores, as the title puts it, The Pattern of Friendship – the web of connections between Ravilious and the group of friends, collaborators and like-minded artist-craftsmen around him. Edward Bawden is of course well represented, as are John and Paul Nash, Barnett Freedman, Douglas Percy Bliss and the less well known Thomas Hennell. Happily the women in the Ravilious circle also get their due here – his multiply talented wife Tirzah Garwood, the engraver and textile designer Enid Marx, painter-designer Peggy Angus, painter-printmaker Helen Binyon... And, both revelations to me, Diana Low and Bliss's wife Phyllis Dodd. The latter is represented by a group of superb, high-impact portraits in oils, including one of Ravilious – that's it at the top of this post. And Diana Low – with whom Ravilious had an affair (she was not the only one) – is represented by an extraordinary portrait of her mentor William Nicholson.

It looks unfinished but is quite perfect as it is – that yellow waistcoat, that blue cushion are worthy of Nicholson himself, and the pose and facial expression perfectly capture the essence of the man.

This remarkable painting hangs with Nicholson's return of the compliment, his harshly lit portrait of Diana Law, the yellow curtain rhyming with his waistcoat.

This is a terrific exhibition, hugely enjoyable, impressive without being overpowering – and, in the end, as Ravilious's death draws near, very moving. It's impossible to read Edward Bawden's letter of condolence to the dazed and grieving Tirzah without the eyes misting up.

It's a big exhibition, but with none of the oppressive feel of a blockbuster. There's such a rich variety of material – paintings and drawings, prints of all kinds, textiles, illustrated books, wallpapers, posters, marbled papers – and most of what is on show is so full of energy, humour and good cheer that it can only lift the spirits. The mood is only broken by the late watercolours painted by Ravilious when he was at sea as a war artist (before he disappeared on a flight over Iceland); these remarkable paintings convey a quite unexpected sense of mental turmoil and impending tragedy.

But this exhibition is about much more than Ravilious. It explores, as the title puts it, The Pattern of Friendship – the web of connections between Ravilious and the group of friends, collaborators and like-minded artist-craftsmen around him. Edward Bawden is of course well represented, as are John and Paul Nash, Barnett Freedman, Douglas Percy Bliss and the less well known Thomas Hennell. Happily the women in the Ravilious circle also get their due here – his multiply talented wife Tirzah Garwood, the engraver and textile designer Enid Marx, painter-designer Peggy Angus, painter-printmaker Helen Binyon... And, both revelations to me, Diana Low and Bliss's wife Phyllis Dodd. The latter is represented by a group of superb, high-impact portraits in oils, including one of Ravilious – that's it at the top of this post. And Diana Low – with whom Ravilious had an affair (she was not the only one) – is represented by an extraordinary portrait of her mentor William Nicholson.

It looks unfinished but is quite perfect as it is – that yellow waistcoat, that blue cushion are worthy of Nicholson himself, and the pose and facial expression perfectly capture the essence of the man.

This remarkable painting hangs with Nicholson's return of the compliment, his harshly lit portrait of Diana Law, the yellow curtain rhyming with his waistcoat.

This is a terrific exhibition, hugely enjoyable, impressive without being overpowering – and, in the end, as Ravilious's death draws near, very moving. It's impossible to read Edward Bawden's letter of condolence to the dazed and grieving Tirzah without the eyes misting up.

Wednesday 20 December 2017

Irene Dunne: A Healthy Perspective

'No triumph of either my stage or screen career has ever rivalled the excitement of trips down the Mississippi on the riverboats with my father.'

So recalled the wonderful Irene Dunne, who was born on this day in 1898, the daughter of a steamboat inspector and a concert pianist/teacher. Her beloved father died when she was 14, which no doubt made her memories of those steamboat trips all the more precious. But Irene Dunne, who was a devout Catholic, maintained a healthy perspective on acting throughout her life, summing up her career thus: 'I drifted into acting and I drifted out. Acting is not everything. Living is.'

In those days, such a realistic perspective was not unusual among film stars, who knew they were lucky and that fame was a bubble. Many of them, of course, had had experience of the seriousness of real life in the depression years and the subsequent world war. And others were simply fun lovers who would never dream of taking themselves of their career seriously. How very different from so many of the actors of today, who seem to regard their profession as some kind of holy calling, an elemental struggle in which they must engage for the good of humanity, all the while offering their (entirely predictable) slant on world events to the slavishly adoring media. Get over yourselves – acting's a job, if you're good at it, that's great, there's really nothing more to be usefully said.

But back to Irene Dunne. She was a versatile actress who was already making a good career in dramas and musicals when she discovered, having been all but forced into it, that she had a rare gift for comedy. Her pairing with Cary Grant in The Awful Truth and My Favorite Wife (inspired, believe it or not, by Tennyson's Enoch Arden) created one of cinema's great double acts – and it worked just as well in the weepie Penny Serenade. It's a great shame they didn't make more films together.

Here's a taste of the Grant-Dunne chemistry at work in The Awful Truth (also featuring Ralph Bellamy and Skippy the dog as 'Mr Smith')...

So recalled the wonderful Irene Dunne, who was born on this day in 1898, the daughter of a steamboat inspector and a concert pianist/teacher. Her beloved father died when she was 14, which no doubt made her memories of those steamboat trips all the more precious. But Irene Dunne, who was a devout Catholic, maintained a healthy perspective on acting throughout her life, summing up her career thus: 'I drifted into acting and I drifted out. Acting is not everything. Living is.'

In those days, such a realistic perspective was not unusual among film stars, who knew they were lucky and that fame was a bubble. Many of them, of course, had had experience of the seriousness of real life in the depression years and the subsequent world war. And others were simply fun lovers who would never dream of taking themselves of their career seriously. How very different from so many of the actors of today, who seem to regard their profession as some kind of holy calling, an elemental struggle in which they must engage for the good of humanity, all the while offering their (entirely predictable) slant on world events to the slavishly adoring media. Get over yourselves – acting's a job, if you're good at it, that's great, there's really nothing more to be usefully said.

But back to Irene Dunne. She was a versatile actress who was already making a good career in dramas and musicals when she discovered, having been all but forced into it, that she had a rare gift for comedy. Her pairing with Cary Grant in The Awful Truth and My Favorite Wife (inspired, believe it or not, by Tennyson's Enoch Arden) created one of cinema's great double acts – and it worked just as well in the weepie Penny Serenade. It's a great shame they didn't make more films together.

Here's a taste of the Grant-Dunne chemistry at work in The Awful Truth (also featuring Ralph Bellamy and Skippy the dog as 'Mr Smith')...

Monday 18 December 2017

Sun in Winter

I learn from the Daily Star – a copy of which happened to be lying around at my barber's – that Britain is soon to be lashed by Storm Dylan. Yes, a hard rain is indeed a-gonna fall, and among the things blowin' in the wind will be, no doubt, the answer, unless of course it's an idiot wind, etc. (more items of Dylan meteorology welcome).

Meanwhile, it's cold, crisp and clear. A good time to warm up in front of a fine sunny landscape by Paul Klee (born on this day in 1879). Above is a Sicilian landscape painting from 1924, one of the fruits of a six-week sojourn in Sicily with his wife, the pianist Lily Stumpf. As he noted in his journal, 'Colour has taken possession of me; no longer do I have to chase after it, I know that it has hold of me for ever... Colour and I are one. I am the painter.'

Meanwhile, it's cold, crisp and clear. A good time to warm up in front of a fine sunny landscape by Paul Klee (born on this day in 1879). Above is a Sicilian landscape painting from 1924, one of the fruits of a six-week sojourn in Sicily with his wife, the pianist Lily Stumpf. As he noted in his journal, 'Colour has taken possession of me; no longer do I have to chase after it, I know that it has hold of me for ever... Colour and I are one. I am the painter.'

Sunday 17 December 2017

The 'Literary Novel'

I caught an interesting talk on Radio 4 this morning on the decline of the 'literary novel' and the flowering of long-form TV drama. In it Zia Haider Rahman – who recently presented an incisive programme on metaphor – accused novelists of 'complicity in their own decline' by 'relinquishing the very things that are [were, surely?] exclusively the province of the novel'. Relinquishing them, that is, to television. That might equally well be seen the other way round: the kind of writers who might have the qualities required to write good novels are understandably eschewing the 'literary novel' in favour of the big money and huge audiences that television offers.

What is the 'literary novel' anyway, and why must it be separated out from other forms of novel? Is the term anything more than a euphemism for novels that don't sell, unless they're lucky enough to win a literary award? Indeed might the term 'literary fiction' be reduced to the circular definition 'novels eligible for literary prizes'? It's essentially a publishers' category, and of recent growth. Surely none of the great novelists of the past thought of themselves as 'literary novelists', rather than just novelists. Even Henry James wrote some of his best work in what we'd now call 'genre fiction', and most of the novels that now clearly belong to the literary canon sold, in their day and since, in large numbers. The likes of John Updike, Philip Roth and Saul Bellow wrote bestsellers and made serious money; they were not confined to some 'literary fiction' ghetto, sustained only by the esteem of their peers and the generosity of academe. Nabokov, surely one of the most literary novelists ever, wrote one of the biggest bestsellers of the postwar years – a bestseller now regarded as one of the great novels of the 20th century. Updike himself vigorously resisted the whole notion of 'literary fiction', a category that could only 'torment people like me who just set out to write books and if anyone wanted to read them, terrific, the more the merrier'.

Of course drama (in whatever medium) and novels (of any kind) are very different beasts, and the particular skills involved in each are not necessarily transferable – indeed they rarely are – so literary novelists are not 'relinquishing' anything to TV drama. It is our culture that has moved – from a novel-reading one to a screen-viewing one. In the end, perhaps, it's simply a matter of 'follow the money'. In any period, the talent, imagination and innovative flair tends to migrate to where the money is – and that, sure as heck, is not in 'literary fiction'.

What is the 'literary novel' anyway, and why must it be separated out from other forms of novel? Is the term anything more than a euphemism for novels that don't sell, unless they're lucky enough to win a literary award? Indeed might the term 'literary fiction' be reduced to the circular definition 'novels eligible for literary prizes'? It's essentially a publishers' category, and of recent growth. Surely none of the great novelists of the past thought of themselves as 'literary novelists', rather than just novelists. Even Henry James wrote some of his best work in what we'd now call 'genre fiction', and most of the novels that now clearly belong to the literary canon sold, in their day and since, in large numbers. The likes of John Updike, Philip Roth and Saul Bellow wrote bestsellers and made serious money; they were not confined to some 'literary fiction' ghetto, sustained only by the esteem of their peers and the generosity of academe. Nabokov, surely one of the most literary novelists ever, wrote one of the biggest bestsellers of the postwar years – a bestseller now regarded as one of the great novels of the 20th century. Updike himself vigorously resisted the whole notion of 'literary fiction', a category that could only 'torment people like me who just set out to write books and if anyone wanted to read them, terrific, the more the merrier'.

Of course drama (in whatever medium) and novels (of any kind) are very different beasts, and the particular skills involved in each are not necessarily transferable – indeed they rarely are – so literary novelists are not 'relinquishing' anything to TV drama. It is our culture that has moved – from a novel-reading one to a screen-viewing one. In the end, perhaps, it's simply a matter of 'follow the money'. In any period, the talent, imagination and innovative flair tends to migrate to where the money is – and that, sure as heck, is not in 'literary fiction'.

Friday 15 December 2017

Dubin's Lives

I've been reading another Bernard Malamud novel – Dubin's Lives this time. Originally published in 1979, it's very much of its time, being a tale of marital infidelity and male mid-life crisis – well, rather beyond mid-life in Dubin's case, as he's 58 years old. William Dubin, who is of course Jewish, is a successful biographer who seems to have spent his working life writing biographies in an unsuccessful attempt to learn how to live, being constitutionally unable to inhabit his own life with much conviction.

As his latest project is to write a biography of D.H. Lawrence, Dubin is clearly heading for trouble – and it finds him in the form of 23-year-old Fanny, the flaky but voluptuous young woman his wife has hired as a house cleaner. Though Dubin rejects her initial (extremely direct) advance, he can't stay away and it's not long before he's taking her on an illicit trip to Venice (addressing her all the while as if giving a lecture – which is apparently what turns her on). The romance collapses ignominiously in Venice, but that is by no means the end of the story; Dubin is not going to get over Fanny, and his life is about to get very complicated...

What makes Dubin's Lives so much better and more interesting than it might have been is the skill with which Malamud plays out the action as at once farcically comic and emotionally tragic, and succeeds in making us genuinely care about the deplorable, myopic and self-absorbed Dubin. He is extraordinary compelling, even addictive company (though one might not wish to know him in real life) and it's actually a wrench to part from him at the end of the novel. Apart from Dubin, the stand-out character is his long-suffering wife Kitty, who knows her husband so well, yet misses so much. You can see how she and Dubin were drawn together by their interlocking weaknesses, why they fit so well together and yet are so unhappy. As the portrait of a marriage, it's painfully convincing.

The novel is set in upstate (and upmarket) New York, and Malamud describes the rural setting and the movements of the seasons with a sharp, even lyrical eye for nature, making landscape and weather major elements in the story. The verstatile Malamud, it seems, was not only an urban novelist.

Dubin's Lives has its faults – including an abrupt and rather unsatisfying ending – and is probably a little too long. It's certainly not the masterpiece The Assistant is, but it's immensely readable, quite often laugh-aloud funny, and totally involving. The foolish, self-alienated William Dubin is a character who lingers in the mind.

There are also some good Jewish jokes along the way, including the one about the rabbi who heard his sexton praying aloud, 'Dear God, you are everything, I am nothing' and remarked witheringly 'Look who says he's nothing!'

As his latest project is to write a biography of D.H. Lawrence, Dubin is clearly heading for trouble – and it finds him in the form of 23-year-old Fanny, the flaky but voluptuous young woman his wife has hired as a house cleaner. Though Dubin rejects her initial (extremely direct) advance, he can't stay away and it's not long before he's taking her on an illicit trip to Venice (addressing her all the while as if giving a lecture – which is apparently what turns her on). The romance collapses ignominiously in Venice, but that is by no means the end of the story; Dubin is not going to get over Fanny, and his life is about to get very complicated...

What makes Dubin's Lives so much better and more interesting than it might have been is the skill with which Malamud plays out the action as at once farcically comic and emotionally tragic, and succeeds in making us genuinely care about the deplorable, myopic and self-absorbed Dubin. He is extraordinary compelling, even addictive company (though one might not wish to know him in real life) and it's actually a wrench to part from him at the end of the novel. Apart from Dubin, the stand-out character is his long-suffering wife Kitty, who knows her husband so well, yet misses so much. You can see how she and Dubin were drawn together by their interlocking weaknesses, why they fit so well together and yet are so unhappy. As the portrait of a marriage, it's painfully convincing.

The novel is set in upstate (and upmarket) New York, and Malamud describes the rural setting and the movements of the seasons with a sharp, even lyrical eye for nature, making landscape and weather major elements in the story. The verstatile Malamud, it seems, was not only an urban novelist.

Dubin's Lives has its faults – including an abrupt and rather unsatisfying ending – and is probably a little too long. It's certainly not the masterpiece The Assistant is, but it's immensely readable, quite often laugh-aloud funny, and totally involving. The foolish, self-alienated William Dubin is a character who lingers in the mind.

There are also some good Jewish jokes along the way, including the one about the rabbi who heard his sexton praying aloud, 'Dear God, you are everything, I am nothing' and remarked witheringly 'Look who says he's nothing!'

Tuesday 12 December 2017

A Word for It...

Earlier today I was enjoying a morning of sparkling frost, deep blue sky and dazzling low sun. It was bitter cold, but the sun was warm on my face – a sensation I've always relished on days like these. There should be a word for it...

And there is, as I discovered at lunchtime, when the nature writer Robert Macfarlane had a spot on Radio 4's The World at One to talk about the rich store of winter words. (As author of the recent Lost Words, he's the go-to guy for this sort of thing.) And there it was – the word for the sensation of warm sun on the face on a cold winter day: apricity.

There's a related verb, to apricate, meaning to bask in the sun (from the Latin apricus, sunny). I must remember that for my next beach holiday: 'I'm going down to the beach to apricate; I may be some time.' Meanwhile I look forward to my next experience of apricity.

And there is, as I discovered at lunchtime, when the nature writer Robert Macfarlane had a spot on Radio 4's The World at One to talk about the rich store of winter words. (As author of the recent Lost Words, he's the go-to guy for this sort of thing.) And there it was – the word for the sensation of warm sun on the face on a cold winter day: apricity.

There's a related verb, to apricate, meaning to bask in the sun (from the Latin apricus, sunny). I must remember that for my next beach holiday: 'I'm going down to the beach to apricate; I may be some time.' Meanwhile I look forward to my next experience of apricity.

Ignorance of History

'Our ignorance of history causes us to slander our own times. The ordinary person today lives better than a king did a century ago, but is ungrateful!'

So wrote Gustave Flaubert (born on this day in 1821) to George Sand in 1871. The words were true enough then, and very much more so today, when living standards for most are beyond the wildest dreams of their grandparents, and yet are taken for granted as a mere minimum. But the widespread ignorance of history that has taken hold in this generation has other, potentially more dangerous effects.

Not only do many take today's sky-high living standards for granted; they also take for granted our freedoms and the democracy that sustains them. Lacking historical perspective, they seem to believe – or act as if – these freedoms represent the default condition of human society, not something historically rare, fragile and vulnerable that must be vigilantly protected and, if necessary, fought for.

They understood these matters better in 1946 (see previous post).

So wrote Gustave Flaubert (born on this day in 1821) to George Sand in 1871. The words were true enough then, and very much more so today, when living standards for most are beyond the wildest dreams of their grandparents, and yet are taken for granted as a mere minimum. But the widespread ignorance of history that has taken hold in this generation has other, potentially more dangerous effects.

Not only do many take today's sky-high living standards for granted; they also take for granted our freedoms and the democracy that sustains them. Lacking historical perspective, they seem to believe – or act as if – these freedoms represent the default condition of human society, not something historically rare, fragile and vulnerable that must be vigilantly protected and, if necessary, fought for.

They understood these matters better in 1946 (see previous post).

Sunday 10 December 2017

'There, intact, were various objects all familiar...'

'The need of our time is for wisdom rather than cleverness, intelligence rather than intellectualism, understanding as well as knowledge. Where there is no vision the people perish.

Our aim is to assist in publicising those liberal and humanistic values whose continued existence is seriously threatened at the present time in our own country as well as elsewhere.'

How's that for a publisher's mission statement? The words are those of Christopher Johnson Publishers Limited of Great Russell Street, London WC1, and I found them on the tattered dust wrapper of a slim volume published in 1946, Keats, Shelley and Rome, An Illustrated Miscellany, compiled by Neville Rogers. It's a collection of essays (and a poem) about the two poets and the house that memorialises them and in which one of them died – the Keats-Shelley Memorial that overlooks the Spanish Steps and the Piazza di Spagna in Rome.

What gives the book its special flavour is the time in which it was written, in the immediate aftermath of the war in which the Eternal City had suffered under both Mussolini and Hitler (and from the activities of partisans). The house on the Spanish Steps had been lucky to survive largely unscathed – and especially lucky in having a formidable Italian woman, Vera Signorelli Cacciatore, as its fiercely protective Curator. The book includes the Signora's vivid eye-witness account of the long-awaited June day in 1944 when the Allied troops finally arrived, so worn out that they immediately lay down to sleep:

'Within five minutes of the order to halt the Piazza was covered with recumbent figures. There in the moonlight slept the soldiers: on the pavements, in the dried-up fountain, on the Scalinata of Santa Trinita dei Monti, propped against the obelisk; pillowed on a haversack, a kerbstone, a doorstep or a comrade...'

These memories – and the related sense of the perilous fragility of civilisation – were still fresh when this little book was published. The first essay is a New York Times correspondent's (A.C. Sedgwick) account of his arrival in Rome with the Allied troops on the day of liberation. With an English Major, he made his way straight to the Keats-Shelley House, climbed the stairs, and was welcomed by Signora Cacciatore. He and the Major were her first welcome visitors in four years.

'There, intact,' writes Sedgwick, 'were various objects all familiar.... There was the smell – more of England than of Italy, or so one thinks – of leather bindings that bewitched Henry James. There was quiet, peace, pause in our lives in which to think, reflect and be thankful that such a haven had been spared, it would appear, by a miracle. Outside – it seemed very far away – we heard the clatter of our mechanised cavalry.'

Keats, Shelley and Rome is dedicated 'To Young Englishmen who Died in Italy'.

Our aim is to assist in publicising those liberal and humanistic values whose continued existence is seriously threatened at the present time in our own country as well as elsewhere.'

How's that for a publisher's mission statement? The words are those of Christopher Johnson Publishers Limited of Great Russell Street, London WC1, and I found them on the tattered dust wrapper of a slim volume published in 1946, Keats, Shelley and Rome, An Illustrated Miscellany, compiled by Neville Rogers. It's a collection of essays (and a poem) about the two poets and the house that memorialises them and in which one of them died – the Keats-Shelley Memorial that overlooks the Spanish Steps and the Piazza di Spagna in Rome.

What gives the book its special flavour is the time in which it was written, in the immediate aftermath of the war in which the Eternal City had suffered under both Mussolini and Hitler (and from the activities of partisans). The house on the Spanish Steps had been lucky to survive largely unscathed – and especially lucky in having a formidable Italian woman, Vera Signorelli Cacciatore, as its fiercely protective Curator. The book includes the Signora's vivid eye-witness account of the long-awaited June day in 1944 when the Allied troops finally arrived, so worn out that they immediately lay down to sleep:

'Within five minutes of the order to halt the Piazza was covered with recumbent figures. There in the moonlight slept the soldiers: on the pavements, in the dried-up fountain, on the Scalinata of Santa Trinita dei Monti, propped against the obelisk; pillowed on a haversack, a kerbstone, a doorstep or a comrade...'

These memories – and the related sense of the perilous fragility of civilisation – were still fresh when this little book was published. The first essay is a New York Times correspondent's (A.C. Sedgwick) account of his arrival in Rome with the Allied troops on the day of liberation. With an English Major, he made his way straight to the Keats-Shelley House, climbed the stairs, and was welcomed by Signora Cacciatore. He and the Major were her first welcome visitors in four years.

'There, intact,' writes Sedgwick, 'were various objects all familiar.... There was the smell – more of England than of Italy, or so one thinks – of leather bindings that bewitched Henry James. There was quiet, peace, pause in our lives in which to think, reflect and be thankful that such a haven had been spared, it would appear, by a miracle. Outside – it seemed very far away – we heard the clatter of our mechanised cavalry.'

Keats, Shelley and Rome is dedicated 'To Young Englishmen who Died in Italy'.

Saturday 9 December 2017

Some Reasons

Some of the reasons why this country was never going to make a fit with political 'Europe' in any of its various forms, from Common Market to EU:

1. English common law (bottom-up as against top-down).

2. A long history of stable democracy and secure borders, free of foreign occupation or conquest.

3. A preference for pragmatic empiricism and inductive reasoning, and a deep distrust of Big Ideas.

4. A unique place in the wider world, the legacy of a long maritime history and a relatively benign, uniquely wide-ranging empire.

5. A national character in which modesty, decency, emotional restraint, fair play and a sense of humour are (or were) prominent features.

6. A natural understanding of, and talent for, popular music. The English equivalent of today's lavish obsequies for Johnny Hallyday would be a state funeral for Shakin' Stevens.

1. English common law (bottom-up as against top-down).

2. A long history of stable democracy and secure borders, free of foreign occupation or conquest.

3. A preference for pragmatic empiricism and inductive reasoning, and a deep distrust of Big Ideas.

4. A unique place in the wider world, the legacy of a long maritime history and a relatively benign, uniquely wide-ranging empire.

5. A national character in which modesty, decency, emotional restraint, fair play and a sense of humour are (or were) prominent features.

6. A natural understanding of, and talent for, popular music. The English equivalent of today's lavish obsequies for Johnny Hallyday would be a state funeral for Shakin' Stevens.

Thursday 7 December 2017

UK City of Larkin 2

So the next UK City of Culture will be Coventry (and why not?). The accolade has now followed Philip Larkin from his workplace (Hull) to his birthplace. It only remains to fill in the gaps with Leicester (Larkin 1946-50) and Belfast (1950-55) and that will be UK culture firmly nailed to the CV of one of its finest poets. And why not?

Birthdays

Sixty-eight today: me and Tom Waits. Birthdays haven't been the same since Edmundo Ros (7 December 1910 - 21 October 2011) went to join the celestial rumba band. And of course the NigeCorp silver band has long been mothballed.

I guess I'm now a soixante-huitard, but in an entirely English sense...

I guess I'm now a soixante-huitard, but in an entirely English sense...

Wednesday 6 December 2017

'An exhibition of reckless species-making'

Pictured above is Swainson's Warbler, one of the many species named by William John Swainson, ornithologist, all-round naturalist and pioneer of the use of lithograhy in zoological illustration. Swainson was a survivor of the bitter classification wars that raged through much of the 19th century (and still do today, in the form of the great Splitters v Lumpers debate). Swainson was an enthusiastic proponent of the Quinarian system of classification (don't ask) developed by William Sharp Macleay – a system that soon fell out of favour. Both Macleay and Swainson emigrated to Australasia (no mean endeavour in those days), Macleay to Australia, Swainson to Wellington, New Zealand, where he bought a huge tract of land – which was promptly claimed by a Maori chief, leading to much legal wrangling.

A visiting American, finding both Macleay and Swainson living in the Antipodes, speculated that they must have been sent into exile 'for the great crime of burdening zoology with a false though much laboured theory which has thrown so much confusion into its classification and philosophical study'.

In 1851 Swainson sailed to Sydney and took up a post as Botanical Surveyor with the Victoria government. His efforts were not well received. William Jackson Hooker opined that 'In my life I think I never read such a series of trash and nonsense. Here is a man who left this country with the character of a first-rate naturalist and of a very first-rate Natural History artist, and he goes to Australia and takes up Botany, of which he is as ignorant as a goose.' Another critic described Swainson's botanical work as 'an exhibition of reckless species-making that, as far as I know, stands unparalleled in the annals of botanical literature'. Scientists didn't mince their words in those days.

Swainson returned to Wellington in 1854, and died on this day in the following year.

A visiting American, finding both Macleay and Swainson living in the Antipodes, speculated that they must have been sent into exile 'for the great crime of burdening zoology with a false though much laboured theory which has thrown so much confusion into its classification and philosophical study'.

In 1851 Swainson sailed to Sydney and took up a post as Botanical Surveyor with the Victoria government. His efforts were not well received. William Jackson Hooker opined that 'In my life I think I never read such a series of trash and nonsense. Here is a man who left this country with the character of a first-rate naturalist and of a very first-rate Natural History artist, and he goes to Australia and takes up Botany, of which he is as ignorant as a goose.' Another critic described Swainson's botanical work as 'an exhibition of reckless species-making that, as far as I know, stands unparalleled in the annals of botanical literature'. Scientists didn't mince their words in those days.

Swainson returned to Wellington in 1854, and died on this day in the following year.

Tuesday 5 December 2017

Intelligence Explosion?

I can't resist passing on this piece (with a tip of the hat to Gareth Williams). It's a fine demolition of the increasingly popular notion that the use of AI (Artificial Intelligence) will at some point create an 'intelligence explosion' that will render us humans redundant and pose an existential threat to us. It's a scifi-inspired projection that rests on a fundamentally flawed idea of intelligence as a kind of superpower, a free-floating contextless phenomenon that, once it's let loose, will carry on doing its work until, as a result of exponential growth in competence, it has far surpassed our puny brains and will lead us into a future where AI is in charge and we humans are no longer needed. Intelligence – artificial or not – simply does not work like that, the author points out. We need not fear this 'explosion'; it will never happen.

Here is the link...

Of course, there may well be reasons to fear the effects of the spread of AI – not least the threat to jobs (this time, interestingly, to high-level as well as low-skill work). But AI isn't going to leave us all sitting around twiddling our thumbs, any more that the rise of digital technology did. AI will, I suspect, find its limits rather sooner than the more excitable futurologists predict. It will bump up against the bounds of the human world that created it and from which is cannot break free.

Here is the link...

Of course, there may well be reasons to fear the effects of the spread of AI – not least the threat to jobs (this time, interestingly, to high-level as well as low-skill work). But AI isn't going to leave us all sitting around twiddling our thumbs, any more that the rise of digital technology did. AI will, I suspect, find its limits rather sooner than the more excitable futurologists predict. It will bump up against the bounds of the human world that created it and from which is cannot break free.

Monday 4 December 2017

Year of the Blues

Another grey, cold December day (with redwings everywhere, heralding colder times ahead) has me yearning for the butterfly-rich days of summer. Clearly it's time to look back over my butterfly year – and wish, as ever, that I'd made more of it.

It started early, with a flurry of Brimstones in February, and continued well into April, including a magical early Orange Tip on a memorable day. When the summer got properly under way, 2017 turned out to be the Year of the Blues (by contrast with 2016's Year of the Hairstreak). A location I'd only managed to find this year proved to be alive with Small Blues, and an exciting highlight of the year was finding a thriving colony of beautiful Silver-Studded Blues at Brookwood – but the most thrilling Blue encounters of the year were with brilliant late-August Adonis Blues, flying in such profusion as I never saw before.

It was also an uncommonly good year for two other chalk downland rarities, the Dark Green Fritillary and Silver-spotted Skipper – at least it was for me – and I saw plenty of White Admirals and Silver-Washed Fritillaries in high summer, and a quite prodigious abundance of Marbled Whites in late spring. A year to look back on with delight. I feel warmer already...

And, happily, I don't have long to look forward to my first butterflies of 2018, as I shall be in New Zealand throughout January, visiting our daughter, son-in-law and grandsons, and enjoying the Monarchs and Yellow Admirals and antipodean coppers and blues.

It started early, with a flurry of Brimstones in February, and continued well into April, including a magical early Orange Tip on a memorable day. When the summer got properly under way, 2017 turned out to be the Year of the Blues (by contrast with 2016's Year of the Hairstreak). A location I'd only managed to find this year proved to be alive with Small Blues, and an exciting highlight of the year was finding a thriving colony of beautiful Silver-Studded Blues at Brookwood – but the most thrilling Blue encounters of the year were with brilliant late-August Adonis Blues, flying in such profusion as I never saw before.

It was also an uncommonly good year for two other chalk downland rarities, the Dark Green Fritillary and Silver-spotted Skipper – at least it was for me – and I saw plenty of White Admirals and Silver-Washed Fritillaries in high summer, and a quite prodigious abundance of Marbled Whites in late spring. A year to look back on with delight. I feel warmer already...

And, happily, I don't have long to look forward to my first butterflies of 2018, as I shall be in New Zealand throughout January, visiting our daughter, son-in-law and grandsons, and enjoying the Monarchs and Yellow Admirals and antipodean coppers and blues.

Saturday 2 December 2017

Billy Burges, Birthday Boy

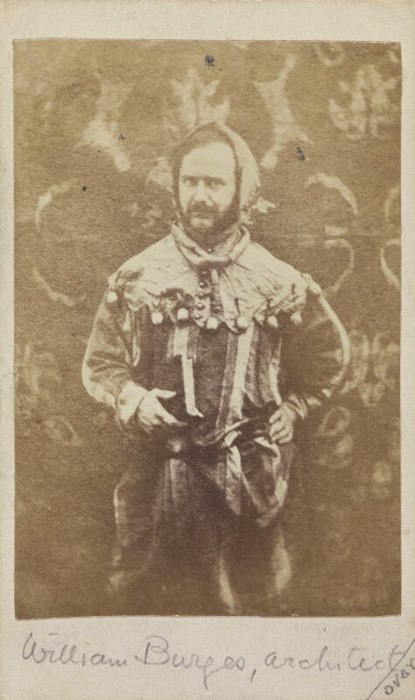

Born on this day 190 years ago was the extraordinary Victorian architect and designer William Burges. He was so 'Gothic' that he wrote in vellum notebooks and had a working portcullis on his London house – but, unlike the more solemn Gothic revivalists, he also regarded the whole thing as an opportunity to have fun, to let the imagination run riot. His fantastically exuberant interiors – as at Cardiff Castle and the nearby Castell Coch – are full of visual jokes and flights of fancy, and give the unmistakable impression of a man enjoying himself (how very unlike, say, Augustus Welby Pugin).

Burges was not yet 30 when, with Henry Clutton, he won the competition to design a new cathedral for Lille, but politics ensured that the winning design was passed over in favour of another (eventually abandoned and perfunctorily finished off when it was half built). His design for Cork Cathedral (impeccable 'Early French'), however, was built, and he went on to create a range of extraordinary buildings, mostly for very rich patrons in rather remote places. All his best interiors offer the complete Burges Gothic experience, designed down to the smallest detail, decorated and furnished entirely with Burges's own creations. The effect is overwhelming, but in a thoroughly enjoyable way, with a wonderfully inventive use of colour and form. It's best taken in small doses though - after a while it's just too much.

'Billy' Burges was a curiously child-like, impish figure, eccentric and flamboyant even by the standards of the Victorian art world. Short, fat and ill-favoured, he particularly enjoyed prancing around in medieval garb – but he was popular and clubbable, and professionally very successful (even if many of his projects never got built). His death was probably accelerated by his addiction to both opium and tobacco (and the opium might well have shaped some of his more extravagant designs). Having fallen ill on a working visit to Cardiff, he lay dying in his London home (the extraordinary Tower House in Holland Park) for three weeks. Among the visitors to his deathbed were Whistler and Oscar Wilde.

Burges was not yet 30 when, with Henry Clutton, he won the competition to design a new cathedral for Lille, but politics ensured that the winning design was passed over in favour of another (eventually abandoned and perfunctorily finished off when it was half built). His design for Cork Cathedral (impeccable 'Early French'), however, was built, and he went on to create a range of extraordinary buildings, mostly for very rich patrons in rather remote places. All his best interiors offer the complete Burges Gothic experience, designed down to the smallest detail, decorated and furnished entirely with Burges's own creations. The effect is overwhelming, but in a thoroughly enjoyable way, with a wonderfully inventive use of colour and form. It's best taken in small doses though - after a while it's just too much.

'Billy' Burges was a curiously child-like, impish figure, eccentric and flamboyant even by the standards of the Victorian art world. Short, fat and ill-favoured, he particularly enjoyed prancing around in medieval garb – but he was popular and clubbable, and professionally very successful (even if many of his projects never got built). His death was probably accelerated by his addiction to both opium and tobacco (and the opium might well have shaped some of his more extravagant designs). Having fallen ill on a working visit to Cardiff, he lay dying in his London home (the extraordinary Tower House in Holland Park) for three weeks. Among the visitors to his deathbed were Whistler and Oscar Wilde.

Friday 1 December 2017

Talking Metaphors

There was an interesting programme on metaphors on Radio 4 the other day, A Picture Held Us Captive – here's the link. In it, one Zia Haider Rahman examines the power of metaphor and its widespread abuse in the public sphere. Richard Dawkins, a prime offender, is in the frame from the get-go, and I was reminded of Marilynne Robinson's comment that 'Finding selfishness in a gene is an act of mind that rather resembles finding wrath in thunder' (and the Australian philosopher David Stove's 'Genes can be no more selfish than they can be (say) supercilious, or stupid'). But the 'selfish gene' metaphor trundles on, crushing all in its path, along with the clutch of biblically-inspired metaphors of the genome as the Book of Life, Code of Codes, etc. Metaphorical language like this is, as more than one contributor points out, massively reductionist, closing down other, more complex and nuanced ways of looking at things. Which is probably the intention.

Of course, there might be a big question that's being skirted here: Is it actually possible to sustain any discourse for long, or to describe any reality, without resorting to metaphor?

Of course, there might be a big question that's being skirted here: Is it actually possible to sustain any discourse for long, or to describe any reality, without resorting to metaphor?

Thursday 30 November 2017

'All our times and tenses'

My father ( d. 1991) has been in my dreams rather a lot lately. Just being there, not packing any particular charge or significance. Often my mother too (d.2013), both of them usually in some stage of middle age, never old. It seems quite unremarkable. We meet without surprise, as in Richard Wilbur's poem (the title poem of his last collection)...

Anterooms

Out of the snowdrift

Which covered it, this pillared

Sundial starts to lift,

Able now at last

To let its frozen hours

Melt into the past

In bright, ticking drops.

Time so often hastens by,

Time so often stops—

Still, it strains belief

How an instant can dilate,

Or long years be brief.

Dreams, which interweave

All our times and tenses, are

What we can believe:

Dark they are, yet plain,

Coming to us now as if

Through a cobwebbed pane

Where, before our eyes,

All the living and the dead

Meet without surprise.

Anterooms

Out of the snowdrift

Which covered it, this pillared

Sundial starts to lift,

Able now at last

To let its frozen hours

Melt into the past

In bright, ticking drops.

Time so often hastens by,

Time so often stops—

Still, it strains belief

How an instant can dilate,

Or long years be brief.

Dreams, which interweave

All our times and tenses, are

What we can believe:

Dark they are, yet plain,

Coming to us now as if

Through a cobwebbed pane

Where, before our eyes,

All the living and the dead

Meet without surprise.

Wednesday 29 November 2017

Yet More Retroprogressive News

Good to hear that the government has plans to reopen several railway lines axed in the notorious 'Beeching cuts'. And this is being done largely to ease the overcrowding on existing routes. The railways, those archaic survivals from the Victorian era, were supposed to wither away in a the whizzy go-ahead age of the motor car – but no, they are busier than ever (at least since the demobilisation after the last war). As that BBC favourite Jimmy Savile (whatever became of him?) used to say, 'This is the age of the train.'

Time for a replay of Flanders and Swann's classic elegy to the old branch lines lost to the Beeching axe...

Time for a replay of Flanders and Swann's classic elegy to the old branch lines lost to the Beeching axe...

Monday 27 November 2017

In a Nutshell

The other day a couple of pleasingly small books on a charity shop shelf caught my eye (I'm always drawn to small books). They were Nutshell Books, from a series of compact factual volumes published by Collins in and around the Sixties. I bought An Outline of English Architecture, took off the murky photographic dust jacket to reveal the pleasing volume shown in the picture, and began to dip into its pages.

It's a book that exactly fits its title, and the outlining is done con brio by one Edmund Vale, a writer with a lively style and a nice turn of phrase. Here he is on the fall of the hard-line antiquarian Camden Society following their restoration of St Sepulchre's in Cambridge:

'They began by pulling down the clerestory, a 15th-century restoration of the Norman original but in contemporary Perpendicular. The little windows were replaced in 19th-century Norman. When it came to putting the clock back in the chancel, they could not resist replacing the Communion table with a supposed near replica of what must have served the pious founders – a fixed stone altar. But parishioners returning to their revived place of worship mistook this touch of architectural virtu for a doctrinal outrage. The Society was sued at law for Popery, convicted, and ordered to remove the rock of offence.

The Camden Society never recovered from this blow to their prestige. But they had succeeded in lifting a vogue which had begun as a genteel folly – a sort of whimsical counterblast to the awful solemnity of neo-classicism – into an even more flourishing solemnity which, in turn, infused its stylistic influence into buildings of every description.'

The running titles are pretty good too – Surprising Discovery (of Ancient Greek architecture), New Post-Roman Speedways, Vogue of the Queen Anne-ites, Dissolution of the Servant Class, But the Romans Got There First... Reading this little volume is rather like reading Osbert Lancaster or John Betjeman. But who was Edmund Vale?

He was, I discover, a prolific author of books on the English countryside and English buildings, among other things – the kind of writer who had a ready market between the wars and in the immediate postwar years. There's a Facebook page devoted to him, curated by his grandson – here's the link. I'll be looking out for more of his books.

An Outline of English Architecture is illustrated with a few photographs and small line drawings. Nowadays a book like this would consist mostly of photographic illustrations, with the words limited to little more than captions. It might, I suppose, be more practically useful, but it wouldn't be a tenth as enjoyable as Edmund Vale's little Nutshell Book.

It's a book that exactly fits its title, and the outlining is done con brio by one Edmund Vale, a writer with a lively style and a nice turn of phrase. Here he is on the fall of the hard-line antiquarian Camden Society following their restoration of St Sepulchre's in Cambridge:

'They began by pulling down the clerestory, a 15th-century restoration of the Norman original but in contemporary Perpendicular. The little windows were replaced in 19th-century Norman. When it came to putting the clock back in the chancel, they could not resist replacing the Communion table with a supposed near replica of what must have served the pious founders – a fixed stone altar. But parishioners returning to their revived place of worship mistook this touch of architectural virtu for a doctrinal outrage. The Society was sued at law for Popery, convicted, and ordered to remove the rock of offence.

The Camden Society never recovered from this blow to their prestige. But they had succeeded in lifting a vogue which had begun as a genteel folly – a sort of whimsical counterblast to the awful solemnity of neo-classicism – into an even more flourishing solemnity which, in turn, infused its stylistic influence into buildings of every description.'

The running titles are pretty good too – Surprising Discovery (of Ancient Greek architecture), New Post-Roman Speedways, Vogue of the Queen Anne-ites, Dissolution of the Servant Class, But the Romans Got There First... Reading this little volume is rather like reading Osbert Lancaster or John Betjeman. But who was Edmund Vale?

He was, I discover, a prolific author of books on the English countryside and English buildings, among other things – the kind of writer who had a ready market between the wars and in the immediate postwar years. There's a Facebook page devoted to him, curated by his grandson – here's the link. I'll be looking out for more of his books.

An Outline of English Architecture is illustrated with a few photographs and small line drawings. Nowadays a book like this would consist mostly of photographic illustrations, with the words limited to little more than captions. It might, I suppose, be more practically useful, but it wouldn't be a tenth as enjoyable as Edmund Vale's little Nutshell Book.

Sunday 26 November 2017

A Matter of Manners

In today's Sunday Times, Niall Ferguson refers to the current pushback against sexual harassment as a 'revolution in manners' (he has well-founded reservations about its potential to 'overshoot', as revolutions do). Ferguson is surely right to identify the whole business as a matter of manners – manners in need of reform – and he's the third person I've noticed so far making this identification (the others were an unlikely pair – Jacob Rees Mogg and Petronella Wyatt).

These days the word 'manners' tends to be narrowly defined in terms of such things as table manners and the fatuous rules of etiquette, but it represents something far bigger and more important than any of that. Manners are the basic lubricant of society, the conventions of behaviour that enable us to live together with minimal friction. The aim of manners, properly understood, is to avoid causing discomfort to other people – discomfort ranging all the way from awkwardness and embarrassment to real pain and distress. It is indeed a matter of convention, and therefore liable to evolve over time, but that doesn't mean it is any less real, important or 'authentic'.

Instead of taking a forensic view of the whole sexual harassment brouhaha as a matter of infringed rights and criminal (or proto-criminal) offences, it might be more illuminating to consider it as being, at least in part, the product of an evolution of manners, of the ways men and women interact with each other. There is clearly criminality in cases where underaged children are involved (though this doesn't seem to apply to the rock stars who thrived in the Seventies) and in the activities of the more thuggish sexual predators (one of whom once occupied the White House). But much of the rest is down to a movement in the barriers of offence. It is no doubt regrettable, but it is a fact that, back in the Seventies, women and girls took a degree of what we would now call sexual harassment as an everyday nuisance, one that most of them were perfectly capable of dealing with. Now we tend to find such behaviour unacceptable – quite right too – but then it was, just, within the boundaries of the acceptable. It was, however, outside the bounds of mannerly behaviour. Such behaviour was, among other things, bad manners – inconsiderate, crude and likely to cause distress.

The English were once famed for their manners – not elaborate displays of fake courtesy but a basic decent concern not to discomfit or pain the other person, to rub along (rubbing along being one of the great English talents, along with muddling through). These manners were closely related to English self-effacement and respect for fair play. Of course they were by no means universal, but they were enough in evidence for the stereotype to gain traction and persist. It is in decline now, in an age of coarsening manners and strident self-assertion, but it does survive (especially away from the urban scrum). We should cherish and encourage it; manners, in this broad humane sense, really matter. They make us what we are. As William of Wykeham put it centuries ago, 'Manners makyth man'.

These days the word 'manners' tends to be narrowly defined in terms of such things as table manners and the fatuous rules of etiquette, but it represents something far bigger and more important than any of that. Manners are the basic lubricant of society, the conventions of behaviour that enable us to live together with minimal friction. The aim of manners, properly understood, is to avoid causing discomfort to other people – discomfort ranging all the way from awkwardness and embarrassment to real pain and distress. It is indeed a matter of convention, and therefore liable to evolve over time, but that doesn't mean it is any less real, important or 'authentic'.

Instead of taking a forensic view of the whole sexual harassment brouhaha as a matter of infringed rights and criminal (or proto-criminal) offences, it might be more illuminating to consider it as being, at least in part, the product of an evolution of manners, of the ways men and women interact with each other. There is clearly criminality in cases where underaged children are involved (though this doesn't seem to apply to the rock stars who thrived in the Seventies) and in the activities of the more thuggish sexual predators (one of whom once occupied the White House). But much of the rest is down to a movement in the barriers of offence. It is no doubt regrettable, but it is a fact that, back in the Seventies, women and girls took a degree of what we would now call sexual harassment as an everyday nuisance, one that most of them were perfectly capable of dealing with. Now we tend to find such behaviour unacceptable – quite right too – but then it was, just, within the boundaries of the acceptable. It was, however, outside the bounds of mannerly behaviour. Such behaviour was, among other things, bad manners – inconsiderate, crude and likely to cause distress.

The English were once famed for their manners – not elaborate displays of fake courtesy but a basic decent concern not to discomfit or pain the other person, to rub along (rubbing along being one of the great English talents, along with muddling through). These manners were closely related to English self-effacement and respect for fair play. Of course they were by no means universal, but they were enough in evidence for the stereotype to gain traction and persist. It is in decline now, in an age of coarsening manners and strident self-assertion, but it does survive (especially away from the urban scrum). We should cherish and encourage it; manners, in this broad humane sense, really matter. They make us what we are. As William of Wykeham put it centuries ago, 'Manners makyth man'.

Friday 24 November 2017

'A splendid person and a most arrogant spirit...'

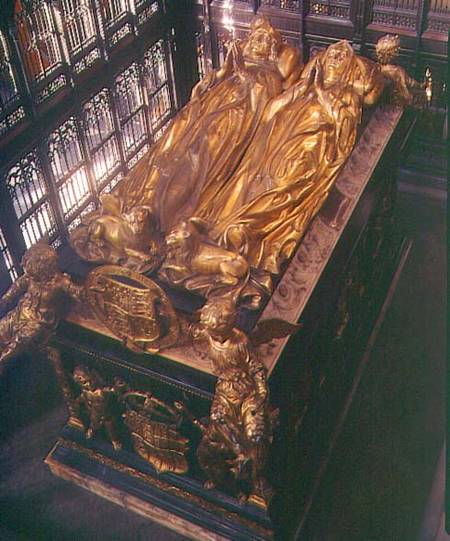

Pietro Torrigiani, great sculptor and violent thug, was born on this day in 1472. He it was who created the astonishing tomb of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York in Westminster Abbey, described by John Pope-Hennessy as 'the finest Renaissance tomb North of the Alps'. England would not see anything remotely comparable in quality or originality until the end of the century, when refugee sculptors from the Low Countries again showed us how much we had to learn from our Continental cousins.

As a young man, Torrigiani, while copying Masaccio's frescoes in the Carmine church with various other learners, got into a row with Michelangelo and punched him so hard that he broke his nose. After this he seems to have fled Florence, turned up again in Rome, then spent some years as a hired soldier – the perfect job for him – before catching the eye of Henry VIII, who wanted a suitably splendid tomb for his parents . He certainly got it, along with various other pieces of work by Torrigiano, most of which were later destroyed by the Puritans.

Cellini, according to himself, refused to come to England from Florence to work with Torrigiano.

'This man,' he recalls, 'had a splendid person and a most arrogant spirit, with the air of a great soldier more than a sculptor, especially in regard to his vehement gestures and his resonant voice, together with a habit he had of knitting his brows, enough to frighten any man of courage. He kept talking every day about his gallant feats among those beasts of Englishmen.'

Beasts, indeed! Still, he left us with one of our greatest works of funerary art.