I came across this striking photograph on Facebook earlier today. It shows the Breton painter Jean-Julien Lemordant, who was severely wounded and blinded at the battle of Arras in 1915. Left for dead, he was taken to Germany as a prisoner, and eventually returned to France in an exchange. His career as a painter, which began with great promise, was now over, but he became an inspirational speaker, extolling the role of the great French artists in keeping the spirit of art and sacrifice alive in France. After the war, he went on to be garlanded with honours in France, and retrospective exhibitions of his work were held in America. Appointed Professor of Aesthetics for life at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, he later designed and built a hotel in Paris (he had studied architecture before switching to art). His living quarters there included a huge, naturally lit studio, which, for obvious reasons, he never used.

Fifty years after he became blind, a series of operations restored his sight. However, the following year, during the événements of May 1968 in Paris, he was killed by tear gas. A terrible and incongruous end for a remarkable man.

His pictures are mostly of Breton scenes, and show the influence of the Fauves and the Pont-Aven painters. Their free brushwork and juicy colours are attractive, and they certainly rise far above the level of picturesque genre scenes. My efforts to download (?upload) a few examples having failed, I can only direct you to Wikipedia and other image sites, where plenty are to be found.

Here is one image that I was able to download – the soldier-artist at peace with his dog...

Monday, 31 January 2022

Jean-Julien Lemordant

Sunday, 30 January 2022

'The heaven-reflecting, usual moon...'

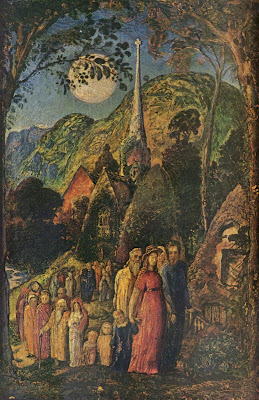

I recently posted Charles Causley's ekphrastic poem on Arshile Gorky's haunting painting of The Artist and His Mother. Here, from the same collection (A Field of Vision), is an evocative sonnet inspired by one of Samuel Palmer's greatest Shoreham paintings, Coming from Evening Church (which hangs in Tate Britain, as we must now call it). He captures perfectly the dream-like, and heaven-like, atmosphere of the scene...

The heaven-reflecting, usual moon

Scarred by thin branches, flows between

The simple sky, its light half-gone,

The evening hills of risen green.

Safely below the mountain crest

A little clench of sheep holds fast.

The lean spire hovers like a mast

Over its hulk of leaves and moss

And those who, locked within a dream,

Make between church and cot their way

Beside the secret-springing stream

That turns towards an unknown sea;

And there is neither night nor day,

Sorrow nor pain, eternally.

This particular painting of Palmer's also inspired another poem, by the Lahore-born English poet Moniza Alvi, who sees it in terms of the figures on a stained-glass window miraculously brought to life...

Coming from Evening Church

after Samuel Palmer, 1830

Suppose we did walk straight out of a stained-glass window,

through the churchyard and up the slope,

an endless gilded procession,

framed by the overarching trees.

Roof, hilltop, spire, a series of echoes.

Leaves printed on the moon

like patterns on a lamp.

We'd be purposeful,

held in the flaring lap of the earth.

Bearded like prophets, tall as saints,

we'd descend to the homesteads,

the ivy as real as we could want it.

And with our children and flowers

we'd keep on walking

in exceptional brilliance,

in the glass certainty of the world.

The painting, like most of the products of Palmer's early genius, owes more to Blake (especially the Songs of Innocence and the woodcut illustrations to Thornton's Virgil) than to anything else. It is suffused with Palmer's sense that, in his Valley of Vision (the Darent valley in Kent), he had found a paradise on earth, a landscape of hills and dells illuminated by the soft, forgiving light of heaven. Though no poet, Palmer did write a good deal of verse in his notebooks and sketchbooks. This early poem, 'Twilight Time', reflects the 'sweet visionary gleam' of many of the Shoreham paintings...

And now the trembling lightGlimmers behind the little hills, and corn,

Ling'ring as loth to part: yet part thou must

And though than open day far pleasing more

(Ere yet the fields, and pearled cups of flowers

Twinkle in the parting light;)

Thee night shall hide, sweet visionary gleam

That softly lookest through the rising dew:

Till all like silver bright;

The Faithful Witness, pure, & white,

Shall look o'er yonder grassy hill,

At this village, safe, and still.

Saturday, 29 January 2022

Auberon Waugh, Novelist: 5

The Auberon Waugh Project (sounds like a wildly unlikely prog rock band) is at an end – that is to say, I have completed my self-imposed mission of (re)reading all of A. Waugh's five novels, in order of publication. It's been fun. Though the quality of the five varies, all are entertaining, readable and often funny, and the Wavian prose – elegant, poised, nuancé – is always a pleasure to read.

The last of the novels, A Bed of Flowers, or As You Like It, published in 1972, is, I think, one of the best, perhaps because it rests on a Shakespearean foundation, as the subtitle suggests. It is Shakespeare's pastoral comedy reimagined as a hippie idyll, in all its sweetness and absurdity. It even has characters called Rosalind and Orlando, Celia, Touchstone, old Adam, the Duke (a drop-out businessman, so nicknamed) and a suitably wise and melancholy Jaques (a former priest turned business advisor turned drop-out). They all fetch up at Williams Farm, in rural Somerset, the run-down family farm of one Wee Willie Williams, a rustic who is portrayed throughout in terms of the broadest caricature. His utterances, often beginning with a sound transcribed as 'Ung', are presented phonetically, thus:

'"Oi doan rightly know how anyone of yous is called," he said. "If Oi call one on you Buttercup, you next one moight be called Marigold or Cow Parsley or bloody Nasturtium Leaves for all Oi Care, har, har, har ... Mistress Cabbage Patch, Oi'll say, har, har, har."'

This kind of thing, I'm sorry to say, I found very funny, especially in counterpoint with the stoned babble of the hippies who, drawn mysteriously to the farm, set up a kind of shambolic commune there. The hippies occasionally watch television, and in one scene they are struck with awe by watching Graham Kerr, the Galloping Gourmet, cooking kidneys: '"Oh my Christ, look what he's doing. He must be stoned out of his mind ... How can he do it? I mean, how can anybody be so cool as to just pour all that mustard into one like cooking utensil without even turning a hair?"' etc. Just the kind of stoned nonsense I remember hearing around me all too often in my misspent youth. Thanks partly to the television, this commune does have some connection with the outside world – and it is what's going on there that forms the other strand of this narrative.

What is going on is, in fact, the British government laying the groundwork for what was to be one of the most terrible civil wars in history – the genocidal campaign by the federal Nigerian government against the Ibos, resulting the destruction of the independent state of Biafra and up to two million deaths, mostly women and children starved to death. Waugh embodies the attitudes that led to this situation in the persons of Frederick Robinson, the ruthless businessman brother of 'the Duke', and of Titus Burns-Oates, a devious and massively self-satisfied éminence grise who ensures that the government shares his dim view of the Ibos and backs to the hilt every action taken against them. The satire here is angry but always cool and controlled. A short factual Epilogue makes clear the serious background to the comedy – and A Bed of Flowers is very much a comedy, culminating in happy endings all round. To somehow combine a hippie idyll with the Biafran war – and remain funny – was quite a challenge, but Waugh, I think, pulled it off; perhaps the Shakespearean inspiration was the key.

It's a shame he never wrote any more novels after this one. None of them is likely to be republished, especially in these woke times, but they are all easily available, quite cheap, from online book dealers. A Bed of Flowers, in its original wrapper (see above), is a bit of a classic of early Seventies design too. And here is the author photo on the back flap...

Thursday, 27 January 2022

For Holocaust Memorial Day

September Song

born 19.6.32 – deported 24.9.42

Geoffrey Hill

Wednesday, 26 January 2022

Endangered Phrases

Here is a list of 50 common sayings that are, according to this piece of research, in danger of passing out of use, or being, as it says here, 'sent to the knacker's yard'. It's a curious list: some of the items seem dangerously new-fangled to me, while others are more obviously archaic or obscure. Nearly all of them have probably passed my lips in recent times, apart from number 3, which I don't like at all (I'm old enough to remember 'cold as charity', which I imagine has now passed out of use. Talking of cold, I've picked up from watching Ivor The Engine the excellent Welsh phrase 'jumping cold'). It's sad to see the fine biblical expression 'pearls before swine' at the top of the list, but I guess it's heartening that nearly three quarters of those involved in this survey expressed regret that traditional phrases were passing out of use. The question is: What are they being replaced with? Or is everyday speech becoming more bland and prosaic, more functional and standardised? Let us hope not. Pip pip.

Tuesday, 25 January 2022

Meanwhile, on Hadrian's Wall...

I see that archaeology is now invoking 'climate change' to draw attention to what might otherwise be considered a not very newsworthy (indeed a largely rather boring) endeavour. This morning I caught Justin Rowlatt, one of the BBC's small army of climate zealots, intoning on TV (I'm in a hotel again) on the subject of the threat a changing climate might pose to Hadrian's Wall, and, sure enough, there's a piece by him, saying much the same things, on the BBC News website. It may or may not be true that the drying out of peatland will pose a real threat to the survival of unusually well preserved relics, but I doubt if this story would have made the news without the 'climate change' spin. And I might add that Hadrian's Wall and its buried relics seem to have survived the Medieval Warm Period in pretty good shape.

Sunday, 23 January 2022

Manet's Mysterious Bar

It's Manet Day again – the birthday (in 1832) of Edouard Manet – a date that seems to have become a fixture on the Nigeness calendar. Usually I celebrate by posting one of the beautiful flower paintings that he made in the last months of his life. This year, however, I'm posting 'A Bar at the Folies Bergères' (a treasure of the Courtauld gallery), the last large-scale painting he completed. And it does feature an exquisite little flower piece in the foreground, the colours set off against the black of the barmaid's dress. Manet painted this picture entirely in his studio, being too ill for a prolonged session at the Folies Bergères. He set up a prop bar counter for the foreground, and painted the background from memory and existing sketches.

It is a haunting, enigmatic painting, one that has attracted much analysis. Most obviously, there seems to be something wrong with the reflection in the mirror (as there often seems to be in the works of Velazquez, Manet's master). Certainly the looming figure of a top-hatted moustachioed man at top right seems out of scale – and why is the barmaid's reflected back so far to the right? This has been explained (perhaps) by an Australian academic, Malcolm Park, who, in a doctoral dissertation, argued that, if Manet's viewpoint is not from a frontal head-on position but from somewhere to the right, everything falls into place, and the barmaid and moustachioed gent are not in conversation at all. The trick is that Manet makes us assume that his viewpoint is frontal. Well, maybe... For myself, I'm happy to let the mystery be, to ponder what it might represent – a vision of paradise, the ultimate sadness of fallen humanity, the world the dying Manet is about to lose? – and simply to enjoy the painterly beauty of what is surely one of Manet's great meditations on the relationship between reality and illusion. And surely a masterpiece.

Two more little details: note, on the left, the wine bottle bearing the artist's signature, and, on the right, a bottle of what is unmistakably Bass – English beer, perhaps denoting Manet's anti-German sentiments.

Friday, 21 January 2022

Sans Gill

The other day, in the course of a meandering telephone call with my brother, the subject got round to Eric Gill, that brilliant engraver and typographer and famously depraved sex maniac. It can only be a matter of time, I quipped, until they start dropping his typefaces... Well, I though I was quipping, but I should have known better: we live in times so mad that events routinely outpace any attempt at satire, particularly in the wonderful world of 'cancel culture'. Sure enough, I now learn that the charity Save the Children is dropping the Gill Sans typeface from its logo, not wishing to link the work of a known abuser with a children's charity. This begs an obvious question: before the charity drew attention to it, how many people would have known it was Gill Sans? Come to that, how many people would even be able to identify Gill Sans? There are plenty of similar typefaces, and nothing about Sans that screams 'Eric Gill', still less 'Eric Gill, child abuser'. A typeface is just a typeface (in Gill Sans's case a 'humanist sans-serif'), too abstract to express anything of its creator's personality, still less his moral character. However, Eric Gill is clearly in the firing line now – as evidenced by the vandal who the other day took a hammer to his Prospero and Ariel outside Broadcasting House (to its credit, the BBC is so far standing firm in its determination to keep its Gill statuary). Eric Gill was a bad man, therefore even his typefaces must be expunged in our oh-so-moral times.

Until Fiona MacCarthy's 1989 biography, Gill's sexual misdeeds were unsuspected: there is nothing in his published work – still less in his typefaces – to suggest them (his erotic wood engravings seem quite straightforward). However, because his sins are now known, his works are to be, if at all possible, suppressed. Had he been a murderer, he would be on safer ground – Caravaggio remains very much in favour, and no one talks of cancelling Benvenuto Cellini or the composer Gesualdo. Come to that, no one takes a hammer to Karl Marx in Highgate cemetery, and 70 million or more deaths can be laid at the door of his political philosophy. Now, if it could be proved that he abused his daughters, that would change things... Or would it?

Thursday, 20 January 2022

Robinson

Muriel Spark's second novel, Robinson, is a curious book – but then, which of her novels isn't?

As the name suggests, it's a castaway adventure of a sort, but the journal-writing narrator is not a man but the familiar fictional proxy of Muriel Spark – cool, sharp-witted, self-aware, steeped in literature and theology. She, the curiously named January Marlow, is one of three survivors from a plane that has crashed on a remote island owned and occupied by the enigmatic Robinson, who lives alone, but for Miguel, a boy he has adopted. One of the survivors – Jimmie, a Hungarian who has learnt his English from works of high literature, turns out to be related to Robinson, in fact his heir. The other is a dodgy character called Tom Wells, who makes a living from a fortune-telling magazine, the sale of lucky charms, and a little blackmail on the side – very Sparkian.

January is repelled by Tom Wells (who is not the only dodgy male in the novel), somewhat attracted to Jimmie, and largely infuriated by Robinson. When the last of these goes missing, to all appearances murdered, things become complicated as all the other three become suspicious of each other. For a while Robinson seems to be developing into a standard whodunit, crossed with an action adventure – scenes of peril in the island's secret caves, a fight described in conventional thriller language – but nothing is ever that simple in Spark's fictional territory...

I enjoyed reading this one – Spark's bright, pared-down style and unpredictable mind are never less than enjoyable – but it is one of her slighter productions. Perhaps, being only her second novel, it was intended to show that she could handle genres that might not have been thought within her range. Happily, though, it remains a curious, Sparkian book. It's a most unusual castaway tale that ends as Robinson does –

'Even while the journal brings before me the events of which I have written, they are transformed, there is undoubtedly a sea-change, so that the island resembles a locality of childhood, both dangerous and lyrical. I have impressions of the island of which I have not told you, and could not entirely if I had a hundred tongues – the mustard field staring at me with its yellow eye, the blue and green lake seeing in me a hard turquoise stone, the goat’s blood observing me red, guilty, all red. And sometimes when I am walking down the King’s Road or sipping my espresso in the morning – feeling, not old exactly, but fusty and adult – and chance to remember the island, immediately all things are possible.'

Tuesday, 18 January 2022

'They lost the off switch in my lifetime...'

Music to Me Is Like Days

Once played to attentive faces

Music has broken its frame

Its bodice of always-weak laces

The entirely promiscuous art

Pours out in public spaces

Accompanying everything, the selections

Of sex and war, the rejections.

To jeans-wearers in zipped sporrans

It transmits an ideal body

Continuously as theirs age. Warrens

Of plastic tiles and mesh throats

Dispense this aural money

This sleek accountancy of notes

Deep feeling adrift from its feelers

Thought that means everything at once

Like a shrugging of cream shoulders

Like paintings hung on park mesh

Sonore doom soneer illy chesh

They lost the off switch in my lifetime

The world reverberates with Muzak

And Prozac. As it doesn’t with poe-zac

(I did meet a Miss Universe named Verstak).

Music to me is like days

I rarely catch who composed them

If one’s sublime I think God

My life-signs suspend. I nod

It’s like both Stilton and cure

From one harpsichord-hum:

Penicillium –

Then I miss the Köchel number.

I scarcely know whose performance

Of a limpid autumn noon is superior

I gather timbre outranks rhumba.

They are the consumers, not me

In my head collectables decay

I’ve half-heard every piece of music

The glorious big one with voice

The gleaming instrumental one, so choice

The hypnotic one like weed-smoke at a party

And the muscular one out of farty

Cars that goes Whudda Whudda

Whudda like the compound oil heart

Of a warrior not of this planet.

Friday, 14 January 2022

Sheeran's Church

I've always found Ed Sheeran's massive success a total mystery. His songs sound to me like, well, so much dead air – too nondescript to register, let alone catch my attention. However, from what little I know of him as a man, he strikes me as a decent sort, a mensch even. Now my opinion of his character has been further raised by the news that he is building not only a church but also a crypt, or underground burial space, in the grounds of his vast Suffolk estate, 'Sheeranville'. The story is told in typically exhaustive style in the Daily Mail, complete with all manner of elaborate graphics. I love that a young pop star, at the height of his fame, should be thinking about death and, presumably, religious worship. And I love that what he proposes to build is not the monument of a megalomaniac but a relatively humble building, with a simple, small burial chamber (nothing like the 'mausoleum' that some have been excitedly reporting). The boat-shaped church I like very much. It looks as if it will sit perfectly in the Suffolk countryside (provided they get the roofing material right – on the architect's drawings it looks suitably unobtrusive).

On one of the aerial photographs of 'Sheeranville', the tower of the nearby parish church – St Michael's, Framlingham – can be seen. This fine church contains several reminders of an age when the building of splendid monuments to oneself and one's family was de rigueur for the wealthier members of society. Chief among them are several tombs of the Howard family, including a grand painted alabaster monument that commemorates Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, the poet.

Howard, having fallen foul of Henry VIII and been imprisoned in the Tower, was executed in 1547 at the age of thirty. He never got to experience the old age he assumes in his poem, 'The Ages of Man'...

Laid in my quiet bed, in study as I were,

I saw within my troubled head a heap of thoughts appear,

And every thought did show so lively in mine eyes,

That now I sigh'd, and then I smil'd, as cause of thought did rise.

I saw the little boy, in thought how oft that he

Did wish of God to scape the rod, a tall young man to be;

The young man eke, that feels his bones with pains oppress'd,

How he would be a rich old man, to live and lie at rest;

The rich old man, that sees his end draw on so sore,

How he would be a boy again, to live so much the more.

Whereat full oft I smil'd, to see how all these three,

From boy to man, from man to boy, would chop and change degree.

And musing thus, I think the case is very strange

That man from wealth, to live in woe, doth ever seek to change.

Thus thoughtful as I lay, I saw my wither'd skin,

How it doth show my dinted jaws, the flesh was worn so thin;

And eke my toothless chaps, the gates of my right way,

That opes and shuts as I do speak, do thus unto me say:

"Thy white and hoarish hairs, the messengers of age,

That show like lines of true belief that this life doth assuage,

Bids thee lay hand and feel them hanging on thy chin,

The which do write two ages past, the third now coming in.

Hang up, therefore, the bit of thy young wanton time,

And thou that therein beaten art, the happiest life define."

Whereat I sigh'd and said: "Farewell, my wonted joy,

Truss up thy pack and trudge from me to every little boy,

And tell them thus from me: their time most happy is,

If to their time they reason had to know the truth of this."

Wednesday, 12 January 2022

Causley's Gorky

Some months ago – in fact on the artist's birthday – I wrote briefly about this extraordinary painting, The Artist and His Mother, by Arshile Gorky. Now, browsing in Charles Causley's last collection, A Field of Vision, I find a wonderfully evocative ekphrastic poem, 'Arshile Gorky's The Artist and His Mother'. The final lines look forward to Gorky's suicide in 1948 when, after a terrible succession of calamities – a fire, cancer, a car accident in which his neck was broken, his wife leaving him – he hanged himself in his studio. On a wooden crate nearby he had written 'Goodbye My Loveds'.

They face us as if we were marksmen, eyes

Unblindfolded, quite without pathos, lives

Fragile as the rose-coloured light, as motes

Of winking Anatolian dust. But in

The landscape of the mind they stand as strong

As rock or water.

The young boy with smudged

Annunciatory flowers tilts his head

A little sideways like a curious bird.

He wears against his history’s coming cold,

A velvet coloured coat, Armenian pants,

A pair of snub-nosed slippers. He is eight

Years old. His mother, hooded as a nun,

Rests shapeless, painted hands; her pinafore

A blank white canvas falling to the floor.

Locked in soft shapes of ochre, iron, peach,

Burnt gold of dandelion, their deep gaze

Is unaccusing, yet accusatory.

It is as if the child already sees

His own death, self-invited, in the green

Of a new world, the painted visions now

Irrelevant, and arguments of line

Stilled by the death of love.

Abandoning

His miracle, he makes the last, long choice

Of one who can no longer stay to hear

Promises of the eye, the colour’s voice.

Tuesday, 11 January 2022

Housekeeping Again

I first became aware of Marilynne Robinson when I read an essay by her in the TLS, shortly after her first novel Housekeeping was published. I only recall that it had something to do with the now famous passage in the novel that begins 'Imagine a Carthage sown with salt...' – and that I was practically gasping with astonished admiration as I read it. Here was someone who wrote like no one else, and who seemed to inhabit a realm of mental and moral seriousness long ago abandoned by most writers: she spoke as if from another age, or none. I duly read Housekeeping and was not disappointed: indeed I found it the most impressive contemporary novel I had read in a long while. After that, Robinson maintained silence on the fiction front for nearly a quarter of a century, while I sustained myself on the wonderful essay collection The Death of Adam and even on Mother Country, half of which is a brilliant demolition of what might be called 'political economy'.

Then, in 2004, came Gilead, and everything changed. Suddenly Robinson became a popular, prize-winning author – an effect that was only amplified when Home won the Orange Prize, among other awards. I loved Gilead, finding it very nearly as impressive – and as different – as Housekeeping, but, sad to say, Robinson began to lose me with Home, which I found a struggle to admire: I got there in the end, but I don't think I would ever reread Home, and I have never read its successors. With fame, Robinson, once so refreshingly reticent, began to have a public voice, to be interviewed and asked her opinion on public affairs, to be, in a word, a kind of literary celebrity. She became less interesting, and, though it grieves me to report it, I began not only to lose interest but to detect something almost of smugness about her public persona. This is no doubt grossly unfair of me – I am talking only of impressions – but it reminded me of a similar transition in Hilary Mantel, another writer (by no means Robinson's equal) whose early work I greatly admired, and who seems to have been adversely affected by fame.

Anyway, all this is by way of saying that, after an interval of a decade or more, I decided to reread Housekeeping again. Would I find it as impressive, as original, as altogether extraordinary as I remembered it? Happily, the answer is an emphatic Yes. This astonishing novel has a uniquely evanescent, indeterminate quality, unstable as the water that is its element; it is like a kind of mirror, but a mirror at once reflective and transparent (like the surface of water). It simply is the mystifying world its young narrator lives in, a world in which she is forever trying to find a path and a meaning – and, above all, a home. Having read it once again, I am as convinced as ever that it is a classic, one of very few written in our times.

'Imagine a Carthage sown with salt, and all the sowers gone, and the seeds lain however long in the earth, till there rose finally in vegetable profusion leaves and trees of rime and brine. What flowering would there be in such a garden? Light would force each salt calyx to open in prisms, and to fruit heavily with bright globes of water–-peaches and grapes are little more than that, and where the world was salt there would be greater need of slaking. For need can blossom into all the compensations it requires. To crave and to have are as like as a thing and its shadow. For when does a berry break upon the tongue as sweetly as when one longs to taste it, and when is the taste refracted into so many hues and savours of ripeness and earth, and when do our senses know any thing so utterly as when we lack it? And here again is a foreshadowing–-the world will be made whole. For to wish for a hand on one’s hair is all but to feel it. So whatever we may lose, very craving gives it back to us again.'

Sunday, 9 January 2022

Don't Look Up: A silly film about human silliness

Last night, in a rare moment of intersection with the zeitgeist, I found myself watching the Netflix movie Don't Look Up. This film, I gather, has divided opinion sharply, the critics by and large panning it, the public loving it (it's already Netflix's third most-watched movie ever). Apparently the most stinking review came from The Guardian – which has to be a recommendation in itself.

However, I knew none of all that when I began watching this contentious piece of work; I just sat back and enjoyed it. I found it a very watchable, entertaining comedy, with some excellent performances – as you'd expect from a cast led by Leonardo DiCaprio, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett, Jennifer Hudson and Mark Rylance. Rylance, in particular, gives a brilliant, affectless turn as the autistic tech genius/monster who is, in effect, running the whole show (and fouling it up). DiCaprio and Hudson are obscure scientists who have discovered a new comet that is undeniably on a collision course with Earth. Needless to say, they have a job getting anyone to believe them, and they are constantly fobbed off and betrayed. Normally, this would make them the obvious heroes of the story – but there's nothing normal about Don't Look Up and these two are some way from heroic.

The film has been widely viewed as a satire on climate change 'denial' and on The Donald. However, what satire there is is pretty lame, and Meryl Streep as the President suggests not Trump but Hillary Clinton. The joke is not on the deniers, or on Trump – it's on all of us, for this is a satire on human nature (which is to say, it's a comedy). Don't Look Up is a silly film about human silliness – a tricky thing to pull off, especially with the critics, who are often too serious-minded to value silliness. I enjoyed it, I laughed quite a lot, and that's good enough for me. Oh, and the final payoff visual gag is a joy.

Saturday, 8 January 2022

A Piper Find

When I'm in Lichfield (as I was again this week) I never need to worry about running out of reading material: the charity bookshops there are notably well stocked, and I always seem to find something of interest. On this visit I spotted Robinson, Muriel Spark's second novel, which I have never read and know nothing about, and – quite an exciting find – Romney Marsh, Illustrated and Described by John Piper, a King Penguin book published in 1950. How could I resist? It cost more money than I usually spend on these occasions, but it was in a good cause (a hospice) and it was still a very fair price – and of course King Penguins, little masterpieces of book design that they are, take up very little shelf space. How could I resist such an attractive volume?

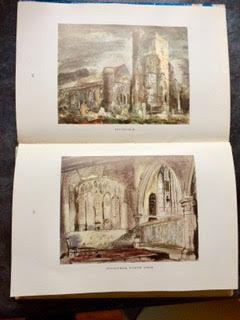

The book is dedicated to Karen* and Osbert Lancaster, and begins with a few quotations ('Some Earlier Views') before Piper's short but informative introduction, which is followed by a list of books and articles about this hauntingly different corner of Kent – big skies, wide horizons, quiet sheep pastures (the sheep are famous) and frequent, isolated churches with strangely bare interiors. Piper is a good descriptive writer – he writes as one who knows his topographical and historical stuff and, like any artist, spends much time looking intensely at the features that interest him, especially, of course, the churches. The book continues with an alphabetical list of Romney March churches, each of which is pithily described, and many of which are illustrated in black and white. Then comes the final section, of colour plates of churches and landscape views.

The plates below show two views of St George, Ivychurch, the 'cathedral of the Marsh'. 'Owing to the pitting and scoring of the stonework by weather,' writes Piper, 'this church takes on the mood of the day in its appearance, looking dark on a grey day and pale and silvery on a clear one'. Piper seems to have drawn it on a day of mixed weather. It could have been worse: as the King (George VI) famously remarked to him at an exhibition, 'You seem to have very bad luck with your weather, Mr Piper.'

Monday, 3 January 2022

'I had not thought that it would be like this'

And here's another case in point: Charles Causley. I knew he was good, I was familiar with several of his children's poems and other popular works, and I remember thinking that, with his simple direct style, he'd have been the perfect successor to John Betjeman as poet laureate (as did Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin). However, I had no idea of just how good he could be until the other day I chanced on his 'Eden Rock', a poem of love and memory and death that seems to me just about perfect...

They are waiting for me somewhere beyond Eden Rock:

My father, twenty-five, in the same suit

Of Genuine Irish Tweed, his terrier Jack

Still two years old and trembling at his feet.

My mother, twenty-three, in a sprigged dress

Drawn at the waist, ribbon in her straw hat,

Has spread the stiff white cloth over the grass.

Her hair, the colour of wheat, takes on the light.

She pours tea from a Thermos, the milk straight

From an old H.P. sauce-bottle, a screw

Of paper for a cork; slowly sets out

The same three plates, the tin cups painted blue.

The sky whitens as if lit by three suns.

My mother shades her eyes and looks my way

Over the drifted stream. My father spins

A stone along the water. Leisurely,

They beckon to me from the other bank.

I hear them call, ‘See where the stream-path is!

Crossing is not as hard as you might think.’

I had not thought that it would be like this.

I think I find this particularly moving because I remember picnics just like this from my own childhood (and indeed have photographs of them). We were rather better equipped, as my father had a picnic canteen, complete with spirit stove and small kettle, in a leather box – and my mother would never have served milk from an old sauce bottle – but the feel of this childhood scene is just the same, and just as poignant. Of course, like Causley's parents when he wrote this, they are long dead now... This is a late poem, from his last collection, A Field of Vision, which I have now ordered from AbeBooks.

Andrew Motion once said that, if he could write a line as perfect as the one that ends 'Eden Rock', he would die a happy man.

Sunday, 2 January 2022

'I am my own and not my own'

My youthful prejudices have often served me well. Not because they were right – they were generally plumb wrong – but because they have deferred my discovery of some wonderful things to the point when I was old enough to appreciate them. Baroque music is a case in point: in my early listening years, I was so wedded to the Romantic orchestral canon that I had little time for the Baroque (and besides, in those days there was far less of it available on record, and it was mostly performed in a decidedly un-Baroque style). Nowadays I listen more to Baroque music than to any other style, and indeed more to chamber music than orchestral.

Among writers, one of my youthful prejudices was against Thom Gunn. It didn't help that he was a product of my own university – that was one more reason to resent his precocious success – but mostly my prejudice was down to my (then fashionable) distaste for traditional poetic form and clear diction, things that today, having reached mature years, I value very highly in poetry. My discovery of how good Thom Gunn could be was long delayed, but gradually I began to enjoy individual poems that I came across – some of which I've posted here – and, after reading his late collection The Man with Night Sweats, I realised that I must read more of this seriously good poet whom I'd so foolishly dismissed.

Browsing in his Poems 1950-1966 last night, I came across a poem appropriate for Christmastide, one that even chimes with the Incarnation sermon I heard on Christmas Day...

Jesus and His Mother

My only son, more God’s than mine,

Stay in this garden ripe with pears.

The yielding of their substance wears

A modest and contented shine,

And when they weep with age, not brine

But lazy syrup are their tears.

‘I am my own and not my own’.

He seemed much like another man,

That silent foreigner who trod

Outside my door with lily rod:

How could I know what I began

Meeting the eyes more furious than

The eyes of Joseph, those of God?

I was my own and not my own.

And who are these twelve labouring men?

I do not understand your words:

I taught you speech, we named the birds,

You marked their big migrations then

Like any child. So turn again

To silence from the place of crowds.

‘I am my own and not my own’.

Why are you sullen when I speak?

Here are your tools, the saw and knife

And hammer on your bench. Your life

Is measured here in week and week

Planed as the furniture you make,

And I will teach you like a wife

To be my own and all my own.

Who like an arrogant wind blown

Where he may please, needs no content?

Yet I remember how you went

To speak with scholars in furred gown.

I hear an outcry in the town;

Who carries that dark instrument?

‘One all his own and not his own’.

Treading the green and nimble sward

I stare at a strange shadow thrown.

Are you the boy I bore alone,

No doctor near to cut the cord?

I cannot reach to call you Lord,

Answer me as my only son.

‘I am my own and not my own’.

The pear is an attribute of the Madonna and Child, and appears in paintings by (among others) Dürer and Bellini. The latter is a beautiful work, with perhaps something of the feel of Gunn's poem...