As 2021 staggers to an end, it's time to look back over a year that has been, for me, rather more mixed than most. It was the year in which, after 71 years of almost uninterrupted good health, I discovered that my mortal frame was, after all, liable to various afflictions – all dealt with now, but very tiresome at the time. And it was a year in which the derangement and dehumanisation of the larger world, driven by the hysterical reaction to a virus, reached such a pitch that at times the psychic weather penetrated even my usually unconquerable soul.

However, however, however... This blog is A Hedonic Resource or it is nothing. So, let us look back on the high points of 2021. Although the New Zealand family remain in enforced exile, thanks to that country's insane approach to the virus, the family in England was enlarged by one more grandson, the delightful and adorable Jack – and, by moving to Lichfield, that family made my life even more Mercian and opened the pleasing prospect of a future life in that fine city.

In January, the month of Jack's birth, I discovered the delicious and health-giving aperitif Cynar , and on the 2nd of February, Candlemas, I saw my first butterfly of the year. Later that month I finished, with regret, my reading of Willa Cather's novels with One of Ours. In March I read Samuel Beckett's extraordinary fragment of Johnsonian drama, Human Wishes, and in April found a church open and unrestricted at last. The swifts returned on May 4th, only to disappear again while the weather deteriorated, before staging a triumphant summer comeback. Also in May I embarked on another 'big read', The Maias by Eça de Queiroz, a hugely enjoyable classic. In June I happened upon the rather wonderful paintings of Jon Redmond, and, in an unrelated development, was converted to pyjamas. I think it was in this month too that I was startled by a communication from a respectable publisher expressing apparently genuine interest in the little butterfly book that I had written over the winter. I have yet to discover what will come of this (as I noted only yesterday, publishing is slow...).

In July I enjoyed (and reviewed) Adam Nicolson's The Sea Is Not Made of Water, and attended a very moving and beautiful funeral. In August I read an enjoyable memoir of Ivy Compton-Burnett by her typist, Cecily Greig. September brought a memorable, indeed magical church-crawling moment in Lincolnshire, and an equally memorable and magical end to the butterfly year. I also enjoyed Roger Scruton's Our Church and Anne Harvey's anthology Elected Friends: Poems For and About Edward Thomas. October began with the wonderful Helen Frankenthaler exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery, and ended with my first walk in a long while with my walking friends. In November I came across a slim volume that has given me much pleasure – John Betjeman's Church Poems, illustrated by John Piper, and in December I treated myself to a facsimile edition of Moses Harris's beautiful butterfly book, The Aurelian.

Much else has happened in my world in this rather too eventful year, and I have enjoyed many more books and poems, paintings, pieces of music and (of course) butterflies than are mentioned here, but those are some of the highlights. I look forward to many more small and large pleasures in the year that is about to unfold, and in that spirit I wish all who browse here a very Happy New Year.

Friday 31 December 2021

Looking Back

Thursday 30 December 2021

Publishing Fast and Slow

In August 1831 Thomas Carlyle came down to London from Craigenputtock to find a publisher for his genre-breaking philosophical novel Sartor Resartus. He left it at the offices of John Murray, with a note requesting that 'no time may be lost in deciding on it' and declaring that 'At latest next Wednesday I shall wait upon you...' This is pretty pushy behaviour for a not very well known journalist and essayist, and suggests that publishing then was, shall we say, a rather more urgent affair than it is now.

Next Wednesday, however, came and went with no word from Murray, so Carlyle took to calling in at the office, always finding Murray out of town. He became increasingly exasperated – 'I have lost ten days by him already' – but eventually Murray agreed to publish. At this point, Carlyle made a fatal mistake by approaching another publisher to see if he could get a better offer. Learning of this, Murray decided to send the manuscript out to a literary friend for an opinion on its merits and its commercial potential. This friend, Henry Hart Milman, reported that Sartor Resartus was too clever, too German, too whimsical, too elaborate and too long to find many English readers. On 6 October Jane Carlyle wrote to her mother: 'They are not going to print the book after all – Murray has lost heart lest it do not take with the public and so like a stupid ass, as he is, has sent the manuscript back.'*

Murray's decision was commercially sound: it would be some years before Sartor Resartus began to be widely read and regarded as a classic (if one that has hardly survived to our time). What is surprising, though, is the speed with which all this was transacted – less than two months from Carlyle's delivery of the manuscript to its final rejection, with at least one serious reading, an initial acceptance and Carlyle's fatal mistake along the way. In that more leisurely age, publishing seems to have moved remarkably fast.

Things were very different when, in 1963, Cynthia Ozick set about getting her first novel published. In her essay 'James, Tolstoy, and My First Novel', she recalls how it took three whole years to achieve publication: six months waiting for the editor who had initially accepted it to come up with the 'suggestions' he had promised to supply; a further 12 months of waiting while said editor assured her he was working on a long list of 'suggestions'; an interview in the course of which it became clear that he had no such list; the eventual delivery, from another editor, of the first 100 pages of the manuscript, densely covered with scribbled 'suggestions'; Ozick's rejection of all these 'suggestions', the editor's agreement, and finally, eventually, publication of Trust, her first novel, exactly as she wrote it. Today, I fear, she would have had many more obstacles – minefields indeed – to negotiate on her way to publication. And it is still a slow, slow business...

* I take all this from Dear Mr Murray: Letters to a Gentleman Publisher, an excellent browsing book that I was given for Christmas.

Sunday 26 December 2021

Christmas Prevails

Well, I managed to get to the cathedral on Christmas morning, and the service did not disappoint. Well, as it was Choral Eucharist, with the splendid organ and the fine choir providing the music, how could it? Even the sermon impressed: the nonsense quotient was gratifyingly low, there was at least one genuine laugh, and it developed into a very sound exposition of the mystery of the Incarnation, taking as its starting point the line (from 'Hark the Herald Angels Sing') 'Veiled in flesh, the Godhead see'. This, we were told, was voted the second most heretical line from a hymn in a recent Twitter poll – though, as the preacher (in fact the Bishop himself) pointed out, those who would vote in such a poll can scarcely be said to be representative of the UK population. The most heretical line, by a large margin, was from 'Away in a Manger' – 'The little Lord Jesus no crying he makes' (if Jesus was fully incarnate, he would surely have cried as lustily as any other newborn). Anyway, it was the beauty of the music, and of the glorious building itself, that made this a Christmas morning service to lift the spirits and revive the soul. Christmas had prevailed over Xmas, as it always, somehow, does.

Friday 24 December 2021

Wednesday 22 December 2021

Past and Present

In a passage in his English Hours, Henry James pays a visit to Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire (which seems to have presented a livelier, and certainly a drunker, scene then than it does now it's an English Heritage site). Finding that 'there was still a good deal of old England in the scene', James goes on: 'Who shall resolve into its component parts any impression of this richly complex English world, where the present is always seen, as it were, in profile, and the past presents a full face?'

It's a striking phrase, and true, and not only of England. The present is always passing before us, on its way to somewhere else – that somewhere else being, of course, the past, which is indeed all around us, presenting its full face, or the remnants of its full face – though what we see of it might equally be regarded as the back view of something still retreating. Whatever, the past is inescapably present in the fabric of England – no more so than in, say, Italy or Greece, but certainly more so than in James's native America. What gives this presence in England its special character is, I think, one thing more than any other: the ubiquity of the English parish church, nearly always old or designed in homage to the old, and present in practically every village, however remote. The steeple of the parish church, appearing above trees, or rising above a cluster of buildings, standing high on a hill or out in the fields, deserted by its village, is perhaps the defining image of England (and the soundtrack would be the gentle cawing of rooks).

All of which calls for a church poem. Not 'Church Going' again, not a Betjeman, but this, by U.A. [Ursula] Fanthorpe, about one of the oldest churches in England still in something like its original form – the wood-built Saxon church of Greensted in Essex...

Stone has a turn for speech.

Felled wood is silent

As mown grass at mid-day.

These sliced downright baulks

Still bear the scabbed bark

Of unconquered Epping

Though now they shore up

Stone, brick, glass, gutter

Instead of leaf or thrush.

Processing pilgrims,

The marvels that drew them –

Headless king, holy wolf –

Have all fined down to

Postcards, a guidebook,

Matins on Sunday.

So old it remembers

The people praying

Outside in the rain

Like football crowds. So old

Its priests flaunted tonsures

As if they were war-cries.

Odd, fugitive, like

A river's headwaters

Sliding a desultory

Course into history.

Saturday 18 December 2021

Best Before

Earlier today, delving in the recesses of the food cupboard, I found the jar of mixed spice I was looking for, and glanced at the label to see what the 'Best Before' date might be. Reader, it was August 1996. This jar of mixed spice had achieved its silver anniversary – impressive, eh? In the month in which is ceased to be Best, we were on a family holiday at Port de Pollença, Majorca, with our then teenage children – the only all-in sun-and-sand package holiday we ever took (our other hols were rather more bespoke). How long ago it seems. How long ago it was...

And now, back in the present, I'm getting ready to head back to Mercia tomorrow – to Derbyshire this time.

Storm and Balm

First, I must apologise for the lack of blogging activity over the past week or so. The reasons are not far to seek...

Back when I was a working man, I fondly imagined that by retiring I would escape the relentless pre-Christmas workstorm that was an inevitable feature of my line of work (and no, I wasn't a department-store Santa). Little did I realise then that the domestic pre-Christmas workstorm can blow just as fiercely as the work one, especially when complicated by much toing and froing to and fro Lichfield, and such matters as my continuing unshakable 'supercold', and a broken-down boiler depriving the house of heating and hot water (fixed now, I'm glad to say). My pre-Christmas mood is, alas, no more festive than it was in my working days, and I look on aghast yet again at the unfolding horror of Xmas (X for Xcess), that frenzy of getting and spending whose spirit seems so entirely divorced from that of Christmas itself, the religious festival that will begin on Christmas Day. I am sure, by the way, that this year's bombardment of ear-bleedingly awful 'festive' 'music' has been louder and more relentless than ever, with yet more emphasis placed on the most unbearable songs, even the most unbearable cover versions of the most unbearable songs. Or is that just me?

Anyway, happily, Christmas – the real Christmas – is coming, and here is a little balm for the spirit – a poem, a simple hymn without music, to remind us of its realities. Richard Wilbur takes his cue not from the Nativity story itself but from Luke's account of Jesus's triumphal entry into Jerusalem...

A Christmas Hymn

And some of the Pharisees from among the multitude said unto him, Master, rebuke thy disciples. And he answered and said unto them, I tell you that, if these should hold their peace, the stones would immediately cry out. - St. Luke XIX.39-40

A stable-lamp is lighted

Whose glow shall wake the sky;

The stars shall bend their voices,

And every stone shall cry.

And every stone shall cry,

And straw like gold shall shine;

A barn shall harbor heaven,

A stall become a shrine.

This child through David’s city

Shall ride in triumph by;

The palm shall strew its branches,

And every stone shall cry.

And every stone shall cry,

Though heavy, dull, and dumb,

And lie within the roadway

To pave his kingdom come.

Yet he shall be forsaken,

And yielded up to die;

The sky shall groan and darken,

And every stone shall cry.

And every stone shall cry

For stony hearts of men:

God’s blood upon the spearhead,

God’s love refused again.

But now, as at the ending,

The low is lifted high;

The stars shall bend their voices,

And every stone shall cry.

And every stone shall cry

In praises of the child

By whose descent among us

The worlds are reconciled.

Sunday 12 December 2021

From Johnson to James – and Richard Cockle Lucas

For reasons unknown, my recent post showing the statue of Dr Johnson under the Christmas lights in Lichfield's market place attracted more views than anything I have put up in a long time – is the good Doctor popular in Sweden perhaps, where an increasingly large number of my readers are to be found, according to Blogger stats (Norway, recently so dominant, seems to have lost interest)?

The statue gets a mention from an unimpressed Henry James in English Hours (1905). He describes it as 'a huge effigy of Dr Johnson, the genius loci, who was constructed, humanly, with very nearly as large an architecture as the great abbey [i.e. cathedral]'. James describes the statue as made of 'some inexpensive composite painted a shiny brown, and of no great merit of design'. This is a harsh judgment indeed, but if the statue was covered with shiny brown paint when James saw it, he would hardly have formed a good impression of it. The paint has long gone, revealing what certainly looks more like real stone than any cheap composite.

The Johnson statue was carved by a sculptor who rejoiced in the name Richard Cockle Lucas, and whose other works included a wax bust of Flora that was bought for a very large sum by Wilhelm von Bode, general manager of the Prussian Art Collections, for the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin. This gentleman was convinced the bust was by Leonardo, and continued to believe this even after Lucas's son, the ambitiously named Albert Dürer Lucas, testified under oath that his father had made it from old candle ends and stuffed it with various bits of rubbish, including newspapers. When staff at the Berlin museum examined the bust, they did indeed find crumpled newspapers from the 1840s stuffed inside it, but that too failed to shake Bode's belief that it was a Leonardo.

Richard Cockle Lucas became increasingly eccentric as he grew older, becoming a firm believer in fairies, and riding around Southampton in a Roman chariot. His visiting cards show him posing in a variety of character costumes. This one shows him 'as a necromancer' –

Saturday 11 December 2021

RIP

Sorry to hear of the death of Michael Nesmith, the most musical and original of the Monkees and, more to the point, an under-appreciated pioneer of country rock. While the Eagles soared to stratospheric fame (on wings as eagles, as it were), Nesmith's efforts with his First National Band and on his own met with little success. One of his later albums is ruefully titled And The Hits Just Keep On Comin'. They didn't (though his song Different Drum was a massive hit for Linda Ronstadt and others).

I've always liked this song, from the album Loose Salute...

Thursday 9 December 2021

What on earth?

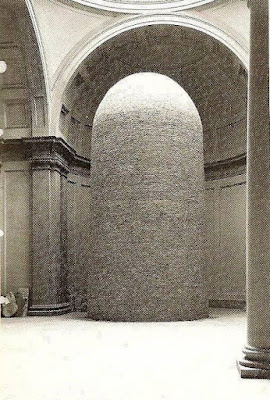

I just came across this photograph, and wondered what on earth it could be...

It is, in fact, Michelangelo's great statue of David, in situ and entirely encased in a brick 'hive' to protect it from bomb damage in 1943 (in the event, when Florence was bombed in 1944, great care was taken to avoid all its artistic treasures). It's an extraordinary image, almost a work of art in its own right – Michelangelo meets Carl Andre. What would it have been like to be present when the statue was liberated from its brick prison? Imagine it emerging, detail by detail, until there was he was, the mighty David, in all his glory.

Wednesday 8 December 2021

Gold

Among my presents yesterday was a very welcome copy of Richard Wilbur's New and Collected Poems (Harcourt Brace, 1988). This handsome edition will replace my Collected Poems 1943-2004 (Waywiser, 2005), which, though obviously more complete, is not an attractive volume and, being too thick for its binding, has split in half along the spine.

After an initial flick through the New & Collected, I decided to open it at random (the Sortes Wilburianae) and see what I found. And I struck gold – this:

Part of a Letter

Easy as cove-water rustles its pebbles and shells

In the slosh, spread, seethe, and the backsliding

Wallop and tuck of the wave, and just that cheerful,

Tables and earth were riding

Back and forth in the minting shades of the trees.

There were whiffs of anise, a clear clinking

Of coins and glasses, a still crepitant sound

Of the earth in the garden drinking

The late rain. Rousing again, the wind

Was swashing the shadows in relay races

Of sun-spangles over the hands and clothes

And the drinkers' dazzled faces,

So that when somebody spoke, and asked the question

Comment s'apelle cet arbre-là?

A girl had gold on her tongue, and gave the answer:

Ca, c'est l'acacia.

Not a big, showy poem, but a perfect miniature, demonstrating Wilbur's technical mastery, his feel for light and water, his brilliant evocation of scene and mood, the music of his language, the exuberant sense of joy and plentitude that his best poems convey. It's from his second collection, Ceremony and Other Poems, and somehow I had never come across it before.

And then this morning, browsing in one of my local charity shops, I spotted Thom Gunn's Poems 1950-1966: A Selection – the 1969 Faber paperback, in astonishingly good condition, priced at, er, £1.00. It is now, needless to say, mine.

Tuesday 7 December 2021

Birthday

Another year gone, and me and Tom Waits turn 72 today. I don't know what he's doing, but me I'm hunkering down, concentrating on staying warm and trying to shake off this interminable cough/cold/catarrh/whatever the hell it is – it's been with me a month now and shows no sign of getting better. Hey ho.

Monday 6 December 2021

'Let me go there'

St Nicholas' Day already... Time for an Advent poem.

Here is one by R.S. Thomas – 'The Coming'. There's a flavour of George Herbert here, but with an overlay of bleakness that is all Thomas's own.

Sunday 5 December 2021

Reminder

It's time for my annual reminder that Christmas is coming and, if you're short of a present or stocking filler for 'anyone interested in churches, in the lost corners of England, or in meditating on mortality' (to quote one of the reviews), you could do worse than slip them a copy of The Mother of Beauty: On the Golden Age of English Church Monuments, and Other Matters of Life and Death. It's still available on Amazon, or, if you'd prefer to bypass Bezos, direct from me at nigeandrew@gmail.com.

The Aurelian

In the interests of research and my own aesthetic pleasure (always a winning combo), I recently bought a copy of the 1986 facsimile edition of Moses Harris's The Aurelian, or Natural History of English Insects; Namely, Moths and Butterflies, Together with the Plants on which they Feed. First published in 1766, this is the most charming, accomplished and beautiful butterfly book of the Georgian age – some might say, of any age, though of course the text reflects the limited entomological knowledge of its time. Our knowledge of Moses Harris is limited too – even the date of his death is unknown – but he describes himself as a 'Painter who has made this Part of Natural History his Study and has bred most of the Flies [butterflies] and Insects for these twenty years'. The delightful frontispiece of The Aurelian is almost certainly a self-portrait, showing Harris elegantly dressed and posing at his ease, his long, two-handled net on his knees, and some of his prize catches displayed around him in oval boxes. The setting is gloriously sylvan, and in the woodland ride behind him a fellow enthusiast stalks his prey. Beneath this idyllic image of an English aurelian's paradise are inscribed words from Psalm 111: 'The works of the Lord are great, sought out of all them that have pleasure therein.'

This beautiful book will do much to help me through the cold, dark, butterflyless months of winter.

Friday 3 December 2021

Nigeliana

The one and only Dave Lull recently sent me a link to a piece in The Oldie written by a fellow member of the dwindling tribe of Nigels. Sadly no mention of Half Man Half Biscuit's Nigel Blackwell, or Spinal Tap's Nigel Tufnel, but otherwise it's a pretty good survey of Nigels past and present.

There is no denying that, as Nigel Pullman notes, the name has what might be called an 'image problem' – and one that seems to have deep roots. I was startled the other day to come across this passage in The Skin Chairs, a novel by the rather wonderful Barbara Comyns (The Vet's Daughter, Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, etc.), written in 1962 but set in the Twenties. To set the scene... The young narrator is living with her family in reduced circumstances, and one of her older sisters, Polly, has become scandalously involved with a boy they nickname the Golden Boy, or Goldy. He is a last-year student at the local grammar school, but, 'unlike the other grammar school boys, he had a certain glamour, and we once overheard him tell a man at a petrol station [...] that he was joining his parents in the Middle East when he had finished his education. Although he was a boarder, he used to stroll around the town capless, his golden hair flowing and glowing in the sun, which always seemed to be shining on him. He walked with a casual grace and often had a faint smile on his face, which I thought attractive but Esmé said was a smirk. It was I who christened him the Golden Boy, and Esmé who remarked that all that glitters is not gold.'

In due course, Polly is rescued from her entanglement with the Golden Boy – whose name has now come to light – and returns home to her family. 'Just as I was going to sleep I suddenly found myself laughing. "Nigel!" I whispered. "That's just the sort of name Goldy would have ... Nigel ..."'

Well really I meantersay chiz chiz, as my namesake N. Molesworth night say.

Thursday 2 December 2021

Turner Time Again

Talking of vanity, I see that something called Array Collective has won this year's Turner Prize with a re-creation of an Irish pub interior. If only O'Neill's had thought to apply...

Having recently read Peter Ackroyd's pithy short biography of Turner, I cannot imagine the great man approving of this, or almost any, winner of the prize awarded in his name. The whole thing has descended into a dismal farce, and should be either scrapped or renamed. A new Turner Prize for painting – you know, skilfully and artistically applying paint to a surface – might be an idea. There are still good painters out there.

Under the Lights

Under the Christmas lights on Lichfield's market place, Samuel Johnson sits brooding on the vanity of human wishes.

'Nothing is more hopeless than a scheme of merriment.'