I recently heard the track below on Radio 3, and it rooted me to the spot. A few days later, I held in my hands the album from which it is taken – The Sound of Light, pieces by Rameau played by Musica Aeterna under the wunderkind conductor Teodor Currentzis. I've been playing it repeatedly, and when you listen to this, the Entrée pour les Muses, les Zéphyrs, les Saisons, les Heures et les Arts from Les Boréades, I think you'll understand why. Here are charm, delight and wonder in concentrated form...

Tuesday 30 June 2020

Cue Music

In times like these, I'm sure we all must feel the need from time to time to (in Patrick Kurp's words) 'address the charm, delight and wonder deficit'. For me, the shortest way to charm, delight and wonder is through music – a medium that can be put to programmatic and descriptive uses, but in its purest from is an end in itself; it is 'about' nothing else. As a result music communicates directly, without mediation, straight to the nerve ends, in a way that marks it out from other art forms.

I recently heard the track below on Radio 3, and it rooted me to the spot. A few days later, I held in my hands the album from which it is taken – The Sound of Light, pieces by Rameau played by Musica Aeterna under the wunderkind conductor Teodor Currentzis. I've been playing it repeatedly, and when you listen to this, the Entrée pour les Muses, les Zéphyrs, les Saisons, les Heures et les Arts from Les Boréades, I think you'll understand why. Here are charm, delight and wonder in concentrated form...

I recently heard the track below on Radio 3, and it rooted me to the spot. A few days later, I held in my hands the album from which it is taken – The Sound of Light, pieces by Rameau played by Musica Aeterna under the wunderkind conductor Teodor Currentzis. I've been playing it repeatedly, and when you listen to this, the Entrée pour les Muses, les Zéphyrs, les Saisons, les Heures et les Arts from Les Boréades, I think you'll understand why. Here are charm, delight and wonder in concentrated form...

Sowell's Principle

I'm not planning to make 'Quote of the Day' a daily feature, but I couldn't resist this from the great American economist (and wonderfully lucid writer) Thomas Sowell, who turns 90 today:

'I write only when I have something to say. The big disadvantage of this is that it can mean a lot of down time.'

This can also, of course, be seen as a big advantage, for those not obliged to earn their living by writing...

There are all too many writers – perhaps a majority – who clearly don't live by Sowell's principle.

'I write only when I have something to say. The big disadvantage of this is that it can mean a lot of down time.'

This can also, of course, be seen as a big advantage, for those not obliged to earn their living by writing...

There are all too many writers – perhaps a majority – who clearly don't live by Sowell's principle.

Monday 29 June 2020

Quote of the Day

'Children find everything in nothing; men find nothing in everything.'

Giacomo Leopardi, born on this day in 1798.

Anyone who has spent time with very young children will know the truth of this. We adults can take steps to guard ourselves against falling into the latter category, chiefly by giving thanks and paying attention.

Giacomo Leopardi, born on this day in 1798.

Anyone who has spent time with very young children will know the truth of this. We adults can take steps to guard ourselves against falling into the latter category, chiefly by giving thanks and paying attention.

Sunday 28 June 2020

Shandy Hall

Wading through 'my papers', I am reminded of how many of England's literary shrines I visited in the course of my hack work – so many that at one time I envisaged making a book of them. Just now I came across a piece I wrote (I think with that book in mind) about one of the least known of those literary shrines: Shandy Hall, in the delightful stone-built village of Coxwold, near Thirsk, in North Yorkshire. The name is doubly apt: in Yorkshire dialect 'shandy' means 'slightly crazy, eccentric, off-kilter' – a fair description of the house itself, which proceeds erratically from a huge ancient stone chimney at one end to a correct Georgian façade at the other – and Shandy Hall was the home, from 1760 to 1768, of Laurence Sterne, the vicar of Coxwold, who wrote his comic masterpiece, Tristram Shandy, within its shandy walls.

The house, which is not large, was rescued from a state of dereliction bordering on collapse by the late Kenneth Monkman, a Sterne enthusiast and scholar, and his wife Julia. Monkman founded a trust, launched an appeal, set about restoring the house, and, in 1973, finally opened it to the public. Nothing that was in the house when Sterne lived there had survived, but a few items came back, and the house's prize exhibit, the great Nollekens bust of Sterne (the twin of the bust in the National Portrait Gallery), was, by a fine stroke of luck, picked up in an antique shop. Sterne's own books were virtually impossible to trace, as – unusually for his time – he never put his name in them. However, Monkman assembled a splendid collection of early editions of Sterne's works and titles known to have been in his library, and now they line the walls of Sterne's 'philosophical hut', the little study by the front door where he wrote Tristram Shandy.

It's more than thirty years since I visited Shandy Hall, but I remember it as one of my more enjoyable literary pilgrimages, not least because I was shown round by Kenneth Monkman himself. Since then the library has grown into the world's largest collection of editions of Sterne's works, and the gardens of Shandy Hall, restored and developed by Julia Monkman, have become a major attraction in themselves. Most visitors to this corner of Yorkshire are attracted not by the name of Laurence Sterne but by that of 'James Herriot', the pen name of Jim Wight, the Thirsk vet who wrote All Creatures Great and Small and sold many millions of books. This is 'Herriot Country' and will never be 'Sterne Country' – but if you ever find yourself in the vicinity, do visit Coxwold and its quirky literary shrine. And, while you're there, drop in on the parish church, where Sterne preached (until his health broke), and where his remains are buried – well, they are very probably his remains: I've told that story before.

The house, which is not large, was rescued from a state of dereliction bordering on collapse by the late Kenneth Monkman, a Sterne enthusiast and scholar, and his wife Julia. Monkman founded a trust, launched an appeal, set about restoring the house, and, in 1973, finally opened it to the public. Nothing that was in the house when Sterne lived there had survived, but a few items came back, and the house's prize exhibit, the great Nollekens bust of Sterne (the twin of the bust in the National Portrait Gallery), was, by a fine stroke of luck, picked up in an antique shop. Sterne's own books were virtually impossible to trace, as – unusually for his time – he never put his name in them. However, Monkman assembled a splendid collection of early editions of Sterne's works and titles known to have been in his library, and now they line the walls of Sterne's 'philosophical hut', the little study by the front door where he wrote Tristram Shandy.

It's more than thirty years since I visited Shandy Hall, but I remember it as one of my more enjoyable literary pilgrimages, not least because I was shown round by Kenneth Monkman himself. Since then the library has grown into the world's largest collection of editions of Sterne's works, and the gardens of Shandy Hall, restored and developed by Julia Monkman, have become a major attraction in themselves. Most visitors to this corner of Yorkshire are attracted not by the name of Laurence Sterne but by that of 'James Herriot', the pen name of Jim Wight, the Thirsk vet who wrote All Creatures Great and Small and sold many millions of books. This is 'Herriot Country' and will never be 'Sterne Country' – but if you ever find yourself in the vicinity, do visit Coxwold and its quirky literary shrine. And, while you're there, drop in on the parish church, where Sterne preached (until his health broke), and where his remains are buried – well, they are very probably his remains: I've told that story before.

From the Mad World

Shopping in Sainsburys just now, I was delighted to see that the Argos outlet there is now hung with rainbow-coloured bunting declaring that 'Argos proudly supports the LGBT+ Community'. This was timely, as I'd been agonising for some while over just where Argos stood in relation to the LGBT+ Community, and was quite prepared to take my custom elsewhere if their support was anything less than proud. Now I know just where they stand, I can enjoy their uniquely dehumanised shopping experience with a clear conscience.

Elsewhere in the mad world – to be precise, on a back street of the suburban demiparadise that is my home – three youngish (white) people were standing by the roadside yesterday afternoon, bearing placards stating that 'Black Lives Matter' (and here was me thinking they don't! Thanks for putting me right, guys). They made a rather forlorn spectacle, reminiscent of Father Ted and Father Dougal protesting outside the Craggie Island cinema ('Down with This Sort of Thing'). Mrs Nige, who is more vocal than I am, shouted across at them that they should check out Zuby. I helpfully spelt it out for them, letter by letter. In the unlikely event that they do check him out, they will discover, to their horror, that the very personable Zuby is a rapper and podcaster who, despite his pigmentation, takes an extremely dim view of the Black Lives Matter movement. Can such things be?

Elsewhere in the mad world – to be precise, on a back street of the suburban demiparadise that is my home – three youngish (white) people were standing by the roadside yesterday afternoon, bearing placards stating that 'Black Lives Matter' (and here was me thinking they don't! Thanks for putting me right, guys). They made a rather forlorn spectacle, reminiscent of Father Ted and Father Dougal protesting outside the Craggie Island cinema ('Down with This Sort of Thing'). Mrs Nige, who is more vocal than I am, shouted across at them that they should check out Zuby. I helpfully spelt it out for them, letter by letter. In the unlikely event that they do check him out, they will discover, to their horror, that the very personable Zuby is a rapper and podcaster who, despite his pigmentation, takes an extremely dim view of the Black Lives Matter movement. Can such things be?

Thursday 25 June 2020

Encouraging the Mob

In the light of what's been going on lately on both sides of the Atlantic, it's instructive to read, in Jenny Uglow's excellent The Lunar Men, about certain events that took place in Birmingham in 1791. Here Joseph Priestley, brilliant scientist, Dissenting preacher and outspoken radical, formed a Constitutional Society, whose first act was to hold a public dinner 'for any Friend of Freedom' on the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. (Priestley, naively but genuinely, believed that the revolution in France was going to create Paradise on Earth.) Predictably enough, the dinner, in a Birmingham hotel, drew various hecklers, and some of the guests were pelted with mud and stones as they left. However, the real action began some hours later, when a much more threatening mob descended, only to find that they'd missed the dinner by several hours. So they vented their anger by breaking the windows of the hotel, then set about smashing up Priestley's New Meeting House, tearing out and burning the furnishings, then putting the building to the torch.

The mob then moved on to Priestley's house, a mile away at Fair Hill, from which Priestley and his wife were persuaded to fly. After fending off the rioters for a while, those defending the house also fled in a hail of stones, and the mob moved in and set about destroying the house and its contents, smashing up everything in Priestley's laboratory, not to mention his wine cellar, before finally setting fire to the house and getting to work on destroying the gardens.

The rampage continued, with the mob attacking various houses of supposed Dissenters, then descending on the home of John Ryland, a banker and merchant, which they burnt down. Seven men, drinking in his cellar, were killed when the blazing roof fell in on them. And so it went on, with a total of 27 houses and four meeting houses being attacked by the mob, and at least eight rioters and one special constable being killed. And yet nothing serious was done about it until the rioters started opening the prisons and freeing the inmates. Special constables were hurriedly sworn in, and eventually dragoons arrived and things quietened down.

Why had so little effective action been taken against the rioters? Because the establishment was essentially behind them, regarding them as sturdy defenders of Church and Crown, and had no strong desire to curb their actions, so long as they stayed within certain bounds. The King and others, including even Burke, expressed themselves delighted that Priestley had suffered for his seditious preaching. However, the Home Secretary, Henry Dundas, saw the clear danger in encouraging rioting: that a mob can easily shift its alliance. The pro-Government mob could well become an anti-Government mob – as indeed happened a couple of years later, when the Birmingham mob was crying 'Tom Paine for ever!'. For this reason, among others, the violent and destructive urges that lie not far below the surface of civilised society should never be encouraged. And, by extension, it is never a good idea to stand back and allow the perceived 'good guys' to silence and 'cancel' those they don't approve of; one day, the 'bad guys' might want to do the same thing, and the 'good guys' will discover they have destroyed their own defences.

(Incidentally, it is also instructive to note the remarkably high incidence of 'extreme weather' events in the years covered by The Lunar Men, despite the fact that the industrial revolution had not yet got under way...)

The mob then moved on to Priestley's house, a mile away at Fair Hill, from which Priestley and his wife were persuaded to fly. After fending off the rioters for a while, those defending the house also fled in a hail of stones, and the mob moved in and set about destroying the house and its contents, smashing up everything in Priestley's laboratory, not to mention his wine cellar, before finally setting fire to the house and getting to work on destroying the gardens.

The rampage continued, with the mob attacking various houses of supposed Dissenters, then descending on the home of John Ryland, a banker and merchant, which they burnt down. Seven men, drinking in his cellar, were killed when the blazing roof fell in on them. And so it went on, with a total of 27 houses and four meeting houses being attacked by the mob, and at least eight rioters and one special constable being killed. And yet nothing serious was done about it until the rioters started opening the prisons and freeing the inmates. Special constables were hurriedly sworn in, and eventually dragoons arrived and things quietened down.

Why had so little effective action been taken against the rioters? Because the establishment was essentially behind them, regarding them as sturdy defenders of Church and Crown, and had no strong desire to curb their actions, so long as they stayed within certain bounds. The King and others, including even Burke, expressed themselves delighted that Priestley had suffered for his seditious preaching. However, the Home Secretary, Henry Dundas, saw the clear danger in encouraging rioting: that a mob can easily shift its alliance. The pro-Government mob could well become an anti-Government mob – as indeed happened a couple of years later, when the Birmingham mob was crying 'Tom Paine for ever!'. For this reason, among others, the violent and destructive urges that lie not far below the surface of civilised society should never be encouraged. And, by extension, it is never a good idea to stand back and allow the perceived 'good guys' to silence and 'cancel' those they don't approve of; one day, the 'bad guys' might want to do the same thing, and the 'good guys' will discover they have destroyed their own defences.

(Incidentally, it is also instructive to note the remarkably high incidence of 'extreme weather' events in the years covered by The Lunar Men, despite the fact that the industrial revolution had not yet got under way...)

Wednesday 24 June 2020

To the Common

To celebrate National Liberation Day – that happy day when the hygienists who now run the country decreed that, if we're very very good and obey all their rules, there is a chance that, at some date in the future, we might, just possibly, be allowed to resume living as human beings – I... Actually I wasn't celebrating anything except the gloriously sunny weather when I set out this morning to take a stroll around Ashtead common. I was greeted immediately by a fresh, bright Red Admiral – there seems to have been quite a big emergence of these beauties – and then, as I crossed the open land of Wood Field, large numbers of lovely Marbled Whites, Small Skippers and the inevitable Meadow Browns, with Small Heaths, Large Skippers and the odd Common Blue thrown in. In the woods, I was hoping to see Silver-Washed Fritillaries and White Admirals – spectacular species both – but for a while it looked as though I was going to be disappointed. Then, after some while, a SWF sailed majestically towards me, before pausing, wings closed, on a conveniently head-high leaf, allowing me to enjoy the subtle beauty of his underwings. Soon after that, several more crossed my path, along with the first White Admiral, gliding through alternating sunlight and shadow – now you see it, now you don't. More admirals and more fritillaries appeared as I walked along the ride – eight or ten of each, maybe more of the fritillaries (I wasn't counting). They alone would have made it a magical morning, but I also saw, close up, my first pair of another (much commoner) favourite, the Ringlet – and, as I headed back towards the station, I had a glimpse of what I think might well have been a Purple Emperor in flight, near the top of an oak tree. But it disappeared before I could get a proper look, so I will have to put a query by that famous name.

Tuesday 23 June 2020

The Consolations of Somewhere

I stepped in to the parish church again this morning, to sit a while and add to the 'footfall', and as I was leaving, an elderly gent in a mobility scooter rolled in. I'd seen him around the village before, and we exchanged nods. Continuing on my way, I headed for the nature reserve, and was wandering there when I saw him again. I greeted him and he came over (he was out of his mobility scooter now). We exchanged a few pleasantries and parted. Then, on the road outside, we bumped into each other yet again, so clearly it was time for introductions. His name rang a faint bell...

It turned out that he had attended the same schools, primary and grammar, as me, and had returned to the latter as a teacher, teaching geography, from the late Fifties to the mid-Sixties – so, yes, he had probably taught me: at the age of 70, I had bumped into one of my old schoolmasters. It was strangely cheering, this evidence of long continuity. We 'somewhere' people, 'rooted in one dear perpetual place'...

It turned out that he had attended the same schools, primary and grammar, as me, and had returned to the latter as a teacher, teaching geography, from the late Fifties to the mid-Sixties – so, yes, he had probably taught me: at the age of 70, I had bumped into one of my old schoolmasters. It was strangely cheering, this evidence of long continuity. We 'somewhere' people, 'rooted in one dear perpetual place'...

Sunday 21 June 2020

Escape from Lockdown

Yesterday, for the first time in a long while, I had a day out – a proper day out, taking the train all the way to Lichfield, that lovely and under-appreciated town/city, to meet up with my Derbyshire cousin. Apart from everything else, it was sheer joy just to be heading so far away from home territory (my little patch on the edge of the North Downs) and travelling through countryside I had not seen for months – smartly shorn sheep grazing old pastureland, square-towered churches among trees, rough knobbly scrubland, brick-built small towns... And then to arrive at Lichfield, the spiritual heart of Mercia, where St Chad built his monastery, and where now its successor, the great cathedral that bears his name, raises its three beautiful spires over the brick-and-stone city with its two great pools.

We (my cousin and I) sat in the park and ate a bread-and-cheese picnic while the sun unexpectedly blazed down on us; we sat in Lunar Man Erasmus Darwin's herb garden; we sat and enjoyed the view over Minster Pool; and we sat in the cathedral for socially-distanced silent prayer, having duly submitted to hand sanitising at the door. My cousin lit a candle, but was not allowed to handle it; that high-risk job was entrusted to a latex-gloved usher. Such is the Church of England now. But at least the cathedral was (partly) open, and as glorious as ever. We didn't drink Sangria in the park, but this escape from lockdown was about as near as it gets to a Perfect Day.

We (my cousin and I) sat in the park and ate a bread-and-cheese picnic while the sun unexpectedly blazed down on us; we sat in Lunar Man Erasmus Darwin's herb garden; we sat and enjoyed the view over Minster Pool; and we sat in the cathedral for socially-distanced silent prayer, having duly submitted to hand sanitising at the door. My cousin lit a candle, but was not allowed to handle it; that high-risk job was entrusted to a latex-gloved usher. Such is the Church of England now. But at least the cathedral was (partly) open, and as glorious as ever. We didn't drink Sangria in the park, but this escape from lockdown was about as near as it gets to a Perfect Day.

Friday 19 June 2020

'I am got somewhat rational now...'

One of the pleasures of Patrick Kurp's Anecdotal Evidence blog is his frequent quoting from the letters of Charles Lamb – letters which often sound like Keats in high spirits, scattering puns and good cheer all round. I have never read, or owned, Lamb's letters, so I decided the other day to take the plunge and buy a volume advertised on AbeBooks as The Letters of Charles Lamb.

What came through my letterbox was a small and astonishingly slim volume (the spine is about five-eighths of an inch) of 466 pages, with no space wasted on an introduction, or even an index.

Published by Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co, this compact little book is a joy to handle, and a perfect fit with a jacket pocket. The paper, though thin, is strong and opaque, and the type perfectly clear and readable. If only more books published today were like this – and if only Simpkin, Marshall, etc. had issued a companion volume of Keats's letter, but as far as I can find out, they never did.

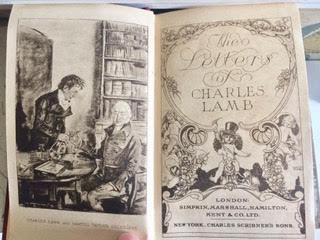

The title spread is very much of its time (the early 1920s) – to the right a jolly neo-Rococo extravaganza by (Alfred) Garth Jones, to the left a fanciful, and frankly awful, picture showing Lamb as a broken-down manservant waiting on a bloated Coleridge. This is dated 1903, and I can't make out the signature of the guilty party...

What first caught my eye, however, was the inscription on the title page: 'One of some books bought out of Auntie ES's gift for my 21st birthday.' The bookshop label shows it was bought at the Davenant Bookshop in Oxford. The date was July 23rd, 1926, and the man who bought it was one Geoffrey Tillotson. This rang a bell – wasn't there a literary critic of that name? Indeed there was – in fact there were two of them, Geoffrey and his wife, who were both professors and distinguished scholars, specialising mostly in Victorian literature. I fancy I might even have read their joint production, Mid-Victorian Studies, back in my university days.

It's always a pleasure to come across a book with a history...

Taking a first look at the Letters last night – this is going to be my bedside reading for some while – I noticed that it has also been lightly margin-marked, most likely by Tillotson himself. The first passage marked, in the very first letter (to Coleridge), is this:

'My life has been somewhat diversified of late. The six weeks that finished last year and began this, your very humble servant spent very agreeably in a mad-house, at Hoxton. I am got somewhat rational now, and don't bite anyone.'

I'm fancy I'm going to enjoy these letters very much.

What came through my letterbox was a small and astonishingly slim volume (the spine is about five-eighths of an inch) of 466 pages, with no space wasted on an introduction, or even an index.

Published by Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co, this compact little book is a joy to handle, and a perfect fit with a jacket pocket. The paper, though thin, is strong and opaque, and the type perfectly clear and readable. If only more books published today were like this – and if only Simpkin, Marshall, etc. had issued a companion volume of Keats's letter, but as far as I can find out, they never did.

The title spread is very much of its time (the early 1920s) – to the right a jolly neo-Rococo extravaganza by (Alfred) Garth Jones, to the left a fanciful, and frankly awful, picture showing Lamb as a broken-down manservant waiting on a bloated Coleridge. This is dated 1903, and I can't make out the signature of the guilty party...

What first caught my eye, however, was the inscription on the title page: 'One of some books bought out of Auntie ES's gift for my 21st birthday.' The bookshop label shows it was bought at the Davenant Bookshop in Oxford. The date was July 23rd, 1926, and the man who bought it was one Geoffrey Tillotson. This rang a bell – wasn't there a literary critic of that name? Indeed there was – in fact there were two of them, Geoffrey and his wife, who were both professors and distinguished scholars, specialising mostly in Victorian literature. I fancy I might even have read their joint production, Mid-Victorian Studies, back in my university days.

It's always a pleasure to come across a book with a history...

Taking a first look at the Letters last night – this is going to be my bedside reading for some while – I noticed that it has also been lightly margin-marked, most likely by Tillotson himself. The first passage marked, in the very first letter (to Coleridge), is this:

'My life has been somewhat diversified of late. The six weeks that finished last year and began this, your very humble servant spent very agreeably in a mad-house, at Hoxton. I am got somewhat rational now, and don't bite anyone.'

I'm fancy I'm going to enjoy these letters very much.

Thursday 18 June 2020

Hallelujah!

My parish church is open again, for private prayer – and open every day, which is a great deal more than it ever managed before. Seeing the notice and the open door today was quite extraordinarily heart-lifting, and walking through that door, back into the familiar space, felt like some kind of homecoming, even though I rarely attend a service these days and am barely part of the life of the parish. Even so, I need that church to be there, and to be open whenever possible; I hadn't realised how deep that need was until those grim months of closure. I hope this welcome reopening is a sign that the church has rethought its place and purpose in the life of the community, and rediscovered 'the power of the parish', as Giles Fraser expresses it in this excellent piece – and that, in Maurice Glasman's words, as quoted by Fraser,

the places denuded of value and purpose are revealed again as a site of meaning, a place where people live and from which they work. The parish has returned as a site of living community, with its land and nature, its character and history, its wounds and its promise. It is the elemental theatre of living community. Its institutions and buildings, including churches, are no longer abandoned monuments to inevitable decline but full of necessity and hope and the new chapter is played out within its bounds. People and place matter in this story. Their particularity is transcendent.

the places denuded of value and purpose are revealed again as a site of meaning, a place where people live and from which they work. The parish has returned as a site of living community, with its land and nature, its character and history, its wounds and its promise. It is the elemental theatre of living community. Its institutions and buildings, including churches, are no longer abandoned monuments to inevitable decline but full of necessity and hope and the new chapter is played out within its bounds. People and place matter in this story. Their particularity is transcendent.

Tuesday 16 June 2020

Does Not Compute

The door of one of our local closed churches, I notice, is now hung with dozens of hearts in various sizes and garish colours, extravagantly signifying devotion to the new cult of NHS worship. To make matters worse, a large notice declares that 'Our Doors Are Closed But God Is Here'. To put it another way, God is here but He can't see you now...

And here's a random, unrelated thought. Just imagine if the spoken word artist 'George the Poet' had been born white, with all the privileges attendant on whiteness: he would surely by now have won at least ten awards, been elected to the National Council of Arts, opened the BBC coverage of the 2018 Royal Wedding, appeared twice on Question Time, turned down an MBE, and become a more or less permanent presence on Radio 4... Wait a minute – er, he's done all that anyway. Does not compute.

And here's a random, unrelated thought. Just imagine if the spoken word artist 'George the Poet' had been born white, with all the privileges attendant on whiteness: he would surely by now have won at least ten awards, been elected to the National Council of Arts, opened the BBC coverage of the 2018 Royal Wedding, appeared twice on Question Time, turned down an MBE, and become a more or less permanent presence on Radio 4... Wait a minute – er, he's done all that anyway. Does not compute.

Monday 15 June 2020

Infected Books

The long overdue reopening of 'non-essential businesses' in England is a welcome reminder of the 'old normal' (i.e. normal life) and seems to be helping to generate a more relaxed atmosphere. Among these 'non-essential businesses' are bookshops, with Waterstone's inevitably to the fore. It's a shop I only visit if there's nothing better (which, sadly, is the case where I live), but I'm glad they're open again and, by all accounts, doing a roaring trade. Buying books in an actual shop is certainly a richer experience than buying online (and if Waterstone's ever had anything I want, I'd do it more often). The down side, however, is that Waterstone's are bending over backwards to reassure the fearful returning shopper by reintroducing a practice that had long ago died out – disinfecting books. Customers will be asked to put aside any book they've touched but not bought, on a trolley which will in due course be trundled away into 72-hour quarantine.

I'm pretty sure Patrick Kurp posted a piece on the disinfecting of library books a few months ago, but I can't for the life of me find it. The story, anyway, is essentially one of a panic, with no real foundation, that blew up in the late 19th century, peaked in the early years of the 20th, then died down – and the point is that it has long been known that there is no evidence that the handling of books can pass on any serious infection: this piece from the Smithsonian magazine gives an account of the panic and its groundlessness. However, I can personally attest that the practice of disinfection did not die out as early as is widely believed: certainly, in my childhood, it was common practice for public libraries to disinfect or incinerate books returned after contact with someone suffering from any of a range of infectious diseases.

And now Waterstone's has revived the notion of infected books – it seems you can't keep a bad idea down, especially in this new age of anxiety.

I'm pretty sure Patrick Kurp posted a piece on the disinfecting of library books a few months ago, but I can't for the life of me find it. The story, anyway, is essentially one of a panic, with no real foundation, that blew up in the late 19th century, peaked in the early years of the 20th, then died down – and the point is that it has long been known that there is no evidence that the handling of books can pass on any serious infection: this piece from the Smithsonian magazine gives an account of the panic and its groundlessness. However, I can personally attest that the practice of disinfection did not die out as early as is widely believed: certainly, in my childhood, it was common practice for public libraries to disinfect or incinerate books returned after contact with someone suffering from any of a range of infectious diseases.

And now Waterstone's has revived the notion of infected books – it seems you can't keep a bad idea down, especially in this new age of anxiety.

Sunday 14 June 2020

Anno Domini

Continuing the lockdown trawl through 'my papers', I'm coming across a lot of features I wrote, years ago, about visits to various places around the country, some of which I've entirely forgotten; others I partly recall, while a few are still quite vivid in my memory. Just now I found a piece on the Russell-Cotes Museum in Bournemouth, which I do remember – who could forget it? The building is eccentric and rather ugly, but interesting, with clever use of natural light. The artworks, though, are a jaw-dropping monument to the ghastly good taste of a late-Victorian hotelier with too much money at his disposal. One of the prize exhibits that I mention in my piece is an enormous painting which, when it was bought, was the most expensive ever sold by any living artist. Sir Merton Russell-Cotes (for it was he) paid £6,900 – around £850,000 in today's money – for Anno Domini, or The Flight into Egypt by Edwin Longsden Long. I had quite forgotten what this looked like, but found it online and was duly enlightened. Here it is...

Well, I suppose if you like this kind of thing, then this is just the kind of thing you'll like – and the bigger the better: this one is about 8ft by 16ft. Long made a highly lucrative speciality of this kind of Biblical epic on canvas, which had immense – and today quite incomprehensible – appeal to the public. Many were displayed in his own gallery, the Edwin Long Gallery, on Bond Street, and after his death some of them were collected together to form the nucleus of a very popular gallery of Christian art which replaced the Gustave Doré gallery. The past in indeed another country.

I always quietly relish coming across these reminders of how soon the most celebrated and expensive art of its age can be entirely forgotten, surviving only as something to cause later generations to stare in disbelief. Damien Hirst and co, this could be you.

Well, I suppose if you like this kind of thing, then this is just the kind of thing you'll like – and the bigger the better: this one is about 8ft by 16ft. Long made a highly lucrative speciality of this kind of Biblical epic on canvas, which had immense – and today quite incomprehensible – appeal to the public. Many were displayed in his own gallery, the Edwin Long Gallery, on Bond Street, and after his death some of them were collected together to form the nucleus of a very popular gallery of Christian art which replaced the Gustave Doré gallery. The past in indeed another country.

I always quietly relish coming across these reminders of how soon the most celebrated and expensive art of its age can be entirely forgotten, surviving only as something to cause later generations to stare in disbelief. Damien Hirst and co, this could be you.

Friday 12 June 2020

'The first fear...'

Coming across this poem by Kay Ryan, I couldn't help thinking that, although it contains wisdom of far wider application, it also has something interesting to say about the response to the Covid epidemic. We seem to be having a deal of trouble unflattening our raft...

We're Building The Ship As We Sail It

The first fear

being drowning, the

ship’s first shape

was a raft, which

was hard to unflatten

after that didn’t

happen. It’s awkward

to have to do one’s

planning in extremis

in the early years -

so hard to hide later:

sleekening the hull,

making things

more gracious.

We're Building The Ship As We Sail It

The first fear

being drowning, the

ship’s first shape

was a raft, which

was hard to unflatten

after that didn’t

happen. It’s awkward

to have to do one’s

planning in extremis

in the early years -

so hard to hide later:

sleekening the hull,

making things

more gracious.

Thursday 11 June 2020

We Are History

My father was, by the standards being applied today, clearly a racist and an imperialist. His language alone would condemn him now, though it was completely commonplace at the time, as was his casually jocular approach to Jews and to foreigners, whom he regarded, in a typically English way, as (a) funny and (b) unfortunate in not having drawn first prize in the lottery of life (by being born English). He cheerfully related 'Rastus' jokes from the comic books of his boyhood, and, as mentioned above, casually used words which now cannot even be printed. As everybody did. The fact that he never did or said an unkind thing to anyone, regardless of colour, race or (a big factor then) social class, and treated everyone with the same good-humoured respect, would count for nothing now against his catalogue of crimes. If there were a statue to him, the thugs of the new fascism would be itching to take it down. If he had a street named after him, it would be on Sadiq Khan's renomination list...

It comes as a shock to realise how little distance on has to travel into the past to find cause for offence, if that is what one's looking for (and large numbers of people seem now to look for little else). Recalling my own schooldays, I remember that blatantly racist jokes were common currency, the more extreme and tasteless the better. They were part of a race to the bottom which also accounted for the popularity of 'sick' jokes and 'spastic' jokes – the kind of things we prefer to forget ever disfigured our minds. And yet, if we boys had then had access to social media, we would have been enthusiastically trading such 'jokes' back and forth. Practically everyone of my generation would have enough on their record to make them social pariahs, and very probably criminals too. And yet we were perfectly ordinary people, representative of our times, just as my father was of his. Those times collectively form The Past, and ultimately History. Astonishingly, the Past was, at the time, the Present; similarly, our Present will become the Past – and heaven knows what the moral judges of the Future might make of it. What is certainly true is that to abolish or censor History is, and can only be, a massively self-destructive enterprise. We are History.

It comes as a shock to realise how little distance on has to travel into the past to find cause for offence, if that is what one's looking for (and large numbers of people seem now to look for little else). Recalling my own schooldays, I remember that blatantly racist jokes were common currency, the more extreme and tasteless the better. They were part of a race to the bottom which also accounted for the popularity of 'sick' jokes and 'spastic' jokes – the kind of things we prefer to forget ever disfigured our minds. And yet, if we boys had then had access to social media, we would have been enthusiastically trading such 'jokes' back and forth. Practically everyone of my generation would have enough on their record to make them social pariahs, and very probably criminals too. And yet we were perfectly ordinary people, representative of our times, just as my father was of his. Those times collectively form The Past, and ultimately History. Astonishingly, the Past was, at the time, the Present; similarly, our Present will become the Past – and heaven knows what the moral judges of the Future might make of it. What is certainly true is that to abolish or censor History is, and can only be, a massively self-destructive enterprise. We are History.

Tuesday 9 June 2020

Year of the Peacock

My first two butterfly sightings of the year – way back in February – were both of Peacocks. They, it turned out, were harbingers of a huge number of Peacocks emerging from hibernation into a gloriously warm and sunny spring. I can't remember when I last saw so many early in the year – they were so numerous that more than once I found myself very nearly treading on one as it lay basking in my path. And now, wherever I go, I see that practically every nettle patch is black with Peacock caterpillars, larvae in their third, fourth and fifth instars (stages of growth, each of which ends in a moult, and the fifth in pupation – so soon the nettles will be hung with chrysalids). Unless something goes seriously wrong – some nasty insect parasite, say – it looks as if this is going to be very much the Year of the Peacock, the year in which that spectacular beauty becomes, improbably, our most abundant and ubiquitous butterfly.

Monday 8 June 2020

Lunar Men

'Has the world gone mad?' is a question that answers itself. However, I can't recall any other time when I've known our society quite so deranged and hellbent on self-destruction. I do my best to avoid the news – especially the broadcast news – but it's impossible to get away from it...

Happily, my latest lockdown 'big read', Jenny Uglow's The Lunar Men, takes me back to a time when things were very different. The story of the Lunar Society, 'the friends who made the future', this is a big book about a big subject – a period of time, in the 18th century, when a group of amateurs, working in an atmosphere of conviviality, friendship and good cheer, sought to unlock the secrets of Nature and thereby reveal (as they cheerfully assumed) the workings of Providence. 'Natural philosophy', the mechanical and fine arts, experimental science, invention, business and manufacture all came together in a period of intellectual ferment in which 'philosophical friendship' sat easily with parties and dances, card games, drinking and conversation late into the night (the Lunar Men would often make their unsteady way home by moonlight). And this extraordinary flowering of the arts and sciences was played out in the true heart of England, the enduring Mercia, or more prosaically the Midlands – in the Potteries of Staffordshire, the rising manufacturing town of Birmingham, and the cities of Derby and Lichfield, the latter home both to the 'father of evolution' Erasmus Darwin and to Samuel Johnson, who said of his native town, 'Sir, we are a city of philosophers; we work with our heads, and make the boobies of Birmingham work for us with their hands.' If the Lunar Men were indeed making the future, they must surely have envisaged a very different one from what lies around us now.

Happily, my latest lockdown 'big read', Jenny Uglow's The Lunar Men, takes me back to a time when things were very different. The story of the Lunar Society, 'the friends who made the future', this is a big book about a big subject – a period of time, in the 18th century, when a group of amateurs, working in an atmosphere of conviviality, friendship and good cheer, sought to unlock the secrets of Nature and thereby reveal (as they cheerfully assumed) the workings of Providence. 'Natural philosophy', the mechanical and fine arts, experimental science, invention, business and manufacture all came together in a period of intellectual ferment in which 'philosophical friendship' sat easily with parties and dances, card games, drinking and conversation late into the night (the Lunar Men would often make their unsteady way home by moonlight). And this extraordinary flowering of the arts and sciences was played out in the true heart of England, the enduring Mercia, or more prosaically the Midlands – in the Potteries of Staffordshire, the rising manufacturing town of Birmingham, and the cities of Derby and Lichfield, the latter home both to the 'father of evolution' Erasmus Darwin and to Samuel Johnson, who said of his native town, 'Sir, we are a city of philosophers; we work with our heads, and make the boobies of Birmingham work for us with their hands.' If the Lunar Men were indeed making the future, they must surely have envisaged a very different one from what lies around us now.

Saturday 6 June 2020

Henry Newbolt

On this day in 1862 was born Henry Newbolt, a poet whose works (or a choice few of them) were part of the soundtrack of my boyhood. My father, who loved to recite verse while shaving in the morning, was especially fond of 'Vitai Lampada' (the one in which 'his captain's hand on his shoulder smote, "Play up, play up, and play the game!"') and 'Drake's Drum' ('Captain, art thou sleeping there below?'), the latter in plain English rather than Devonian.

Newbolt, who was also a novelist, historian and influential government adviser, was to all appearances an utterly conventional establishment figure, but in fact his love life was thoroughly irregular. His wife, one of the Duckworth publishing family, had a passionate and long-running affair with her cousin, 'Ella' Coltman, and, after a couple of years' marriage, Henry too fell in love with Isabella, and they lived from then on in a complicated, but efficiently managed, menage a trois.

Newbolt's nostalgic affection for his alma mater, Clifton College, is apparent in many of his poems (including 'Vitai Lampada'), but before getting a scholarship to Clifton he was a pupil at Caistor Grammar School in Lincolnshire (an establishment whose later alumni/ae included comedienne Dawn French and Strictly Come Dancing's Kevin and Joanne Clifton).

Newbolt, who was also a novelist, historian and influential government adviser, was to all appearances an utterly conventional establishment figure, but in fact his love life was thoroughly irregular. His wife, one of the Duckworth publishing family, had a passionate and long-running affair with her cousin, 'Ella' Coltman, and, after a couple of years' marriage, Henry too fell in love with Isabella, and they lived from then on in a complicated, but efficiently managed, menage a trois.

Newbolt's nostalgic affection for his alma mater, Clifton College, is apparent in many of his poems (including 'Vitai Lampada'), but before getting a scholarship to Clifton he was a pupil at Caistor Grammar School in Lincolnshire (an establishment whose later alumni/ae included comedienne Dawn French and Strictly Come Dancing's Kevin and Joanne Clifton).

Newbolt's poems are not all patriotic tub-thumpers, and sometimes, as in this one inspired by film footage of troops at the front, he could be thoughtful and moving:

The War Films

O living pictures of the dead,

O songs without a sound,

O fellowship whose phantom tread

Hallows a phantom ground –

How in a gleam have these revealed

The faith we had not found.

We have sought God in a cloudy Heaven,

We have passed by God on earth:

His seven sins and his sorrows seven,

His wayworn mood and mirth,

Like a ragged cloak have hid from us

The secret of his birth.

Brother of men, when now I see

The lads go forth in line,

Thou knowest my heart is hungry in me

As for thy bread and wine;

Thou knowest my heart is bowed in me

To take their death for mine.

O songs without a sound,

O fellowship whose phantom tread

Hallows a phantom ground –

How in a gleam have these revealed

The faith we had not found.

We have sought God in a cloudy Heaven,

We have passed by God on earth:

His seven sins and his sorrows seven,

His wayworn mood and mirth,

Like a ragged cloak have hid from us

The secret of his birth.

Brother of men, when now I see

The lads go forth in line,

Thou knowest my heart is hungry in me

As for thy bread and wine;

Thou knowest my heart is bowed in me

To take their death for mine.

Finally, here's a curiosity – Henry Newbolt reading his own poems on a 78rpm disc...

Swift Storm

After the long May heatwave, the weather has certainly broken now. This morning was cool and blustery, with fine rain in the air, as I strolled through the park. Standing, looking vaguely about me, on the slope of a large depression known as the Hog Pit, I suddenly felt something airborne zoom past me, within inches of my face – then another, then another – and I realised I was in the midst of a swift storm. The birds were hurtling down and around the dip, then up again, still close to the ground (and to me), and into the air, circling, then down again, around, up again, all at tremendous speed... There must have been twenty of more birds – impossible to count them when they're moving so fast – obviously coming together to feed on some sudden abundance of flying insect life in the Hog Pit. Within minutes they had all drifted away, and it was as if it had never happened. It was a wonderful, exhilarating experience – as close as I've ever been to a swift in full flight. What magical birds they are...

Thursday 4 June 2020

Going Back

Reading The Betrothed was one of my lockdown projects; the other was writing a short memoir of my life (strictly for family purposes, not for any kind of publication). That too is now done, and I've moved on to something that was more of a retirement project than a lockdown one: going through what I laughingly call 'my papers', i.e. the mass of cuttings, diaries and miscellaneous writings that have been hidden away for some years, unexamined, in two large boxes. So far – and I've barely scratched the surface – it's been a mixed, often interesting and sometimes rewarding experience, and has left me marvelling at the energy I once had, if nothing else. As a penance, I've been ploughing my way through what purports to be a novel, something I laboured over in (I think) the late Seventies and had never looked at since. I'm relieved that no publisher was foolish enough to take it on – and that it's mercifully short.

More interesting, by and large, are the book reviews, many of them of books I have no recollection of ever having read, let alone reviewed. And then there are the radio reviews – several years' worth of weekly reviews for the late lamented Listener. Naturally I have no recollection of most of the programmes I wrote about and am just skimming these pieces before replacing them in the box, for later generations to throw away. I also reviewed books for The Listener, and on the back of a review of Paul Fussell's Caste Marks (long forgotten) in the issue of 7 June 1984, I found this – Gavin Ewart's poetical epitaph for the recently deceased Poet Laureate:

In Memoriam Sir John Betjeman (1906-1984)

So the last date slides into the bracket

that will appear in all future anthologies –

and in quiet Cornwall and in London's ghastly racket

we are now Betjemanless.

Your verse was very fetching

and, as Byron might have written,

there are many poetic personalities around

that would fetch a man less!

Some of your admirers were verging on the stupid,

you were envied by poets (more highbrow, more inventive?);

at twenty you had the bow-shaped lips of a Cupid

(a scuffle with Auden too).

But long before your Oxford

and the visiting of churches

you went topographical – on the Underground

(Metroland and Morden too)!

The Dragon School – but Marlborough a real dragon,

with real bullying, followed the bear of childhood,

a kind of gentlemanly cross to crucify a fag on.

We don't repent at leisure,

you were good, and very British.

Serious, considered 'funny',

in your best poems, strong but sad, we found

a most terrific pleasure.

In Memoriam Sir John Betjeman (1906-1984)

So the last date slides into the bracket

that will appear in all future anthologies –

and in quiet Cornwall and in London's ghastly racket

we are now Betjemanless.

Your verse was very fetching

and, as Byron might have written,

there are many poetic personalities around

that would fetch a man less!

Some of your admirers were verging on the stupid,

you were envied by poets (more highbrow, more inventive?);

at twenty you had the bow-shaped lips of a Cupid

(a scuffle with Auden too).

But long before your Oxford

and the visiting of churches

you went topographical – on the Underground

(Metroland and Morden too)!

The Dragon School – but Marlborough a real dragon,

with real bullying, followed the bear of childhood,

a kind of gentlemanly cross to crucify a fag on.

We don't repent at leisure,

you were good, and very British.

Serious, considered 'funny',

in your best poems, strong but sad, we found

a most terrific pleasure.

Technically, this a typical bravura exercise, with its clever rhyme scheme (I make it abacdefc, with the added subtlety than the penultimate lines of each stanza rhyme with each other) and avoidance of all masculine line endings. Its tone is affectionate, at least towards the end – in contrast to another Ewart poem on Betjeman. It was rumoured that Gavin Ewart – the subject of a very late Larkin poem – was considered as a possible successor to the Laureateship, but not for long, and no wonder: he wrote far too much, and too filthily, about sex.

Now, back to my papers...

Wednesday 3 June 2020

Manzoni on the Riots

The Betrothed, as I've noted before, has some contemporary resonance as a 'plague novel' (though, as I've also pointed out, there is a great gulf between bubonic plague and Covid-19). The chapters devoted to the plague in Milan are brilliant examples of Manzoni's powerful historical imagination. They are well worth reading for their own sake, but certainly have something to tell us about what plague, or a perceived plague, does to human beings. And there are other parts of The Betrothed that also have contemporary resonance, and something to tell us – notably the chapters that revolve around the 'bread riots' in Milan.

As rioting and looting engulf parts of several American cities, accompanied by mindless violence and the destruction of innocent people's businesses, Manzoni's cool words ring true:

'The destruction of sifting machines and bread bins, the wrecking of bakeries and the mobbing of bakers are not really the best methods of ensuring long life to a plenteous supply of bread. But that is one of those philosophical subtleties which a crowd can never grasp. Even without being a philosopher, however, a man will sometimes grasp it straight away, while the whole matter is new to him and he can see it with fresh eyes. It is later, when he has talked and heard others talk about it, that it becomes impossible for him to understand. The thought had struck Renzo at the very beginning, as we have seen, and it kept coming back to him now. But he kept it to himself; for when he looked at all the people around him he could not imagine any of them saying: "Dear brother, if I go wrong, pray correct me, and I will be duly grateful."'

Manzoni understands well how mobs work: how they form, the various cross-currents at work within them, and the way certain operators can exploit these cross-currents to achieve their ends:

'In popular uprisings there are always a certain number of men, inspired by hot-blooded passions, fanatical convictions, evil designs, or a devilish love of disorder for its own sake, who do everything they can to make things take the worst possible turn. They put forward or support the most merciless projects, and fan the flames every time they begin to subside. Nothing ever goes too far for them; they would like to see rioting continue without bounds and without an end. But to counterbalance them, there are always a certain number of other men, equally ardent and determined, who are doing all they can in the opposite direction, inspired by friendship or fellow-feeling for the people threatened by the mob, or by a reverent and spontaneous horror of bloodshed and evil deeds. God bless them for it!'

There seem to be rather too many of the first sort at work in America just now.

As rioting and looting engulf parts of several American cities, accompanied by mindless violence and the destruction of innocent people's businesses, Manzoni's cool words ring true:

'The destruction of sifting machines and bread bins, the wrecking of bakeries and the mobbing of bakers are not really the best methods of ensuring long life to a plenteous supply of bread. But that is one of those philosophical subtleties which a crowd can never grasp. Even without being a philosopher, however, a man will sometimes grasp it straight away, while the whole matter is new to him and he can see it with fresh eyes. It is later, when he has talked and heard others talk about it, that it becomes impossible for him to understand. The thought had struck Renzo at the very beginning, as we have seen, and it kept coming back to him now. But he kept it to himself; for when he looked at all the people around him he could not imagine any of them saying: "Dear brother, if I go wrong, pray correct me, and I will be duly grateful."'

Manzoni understands well how mobs work: how they form, the various cross-currents at work within them, and the way certain operators can exploit these cross-currents to achieve their ends:

'In popular uprisings there are always a certain number of men, inspired by hot-blooded passions, fanatical convictions, evil designs, or a devilish love of disorder for its own sake, who do everything they can to make things take the worst possible turn. They put forward or support the most merciless projects, and fan the flames every time they begin to subside. Nothing ever goes too far for them; they would like to see rioting continue without bounds and without an end. But to counterbalance them, there are always a certain number of other men, equally ardent and determined, who are doing all they can in the opposite direction, inspired by friendship or fellow-feeling for the people threatened by the mob, or by a reverent and spontaneous horror of bloodshed and evil deeds. God bless them for it!'

There seem to be rather too many of the first sort at work in America just now.

Monday 1 June 2020

Christo and Koch

Hearing of the death of Christo – the artist who got famous by wrapping up very very big things, up to and including stretches of coastline – set my mind wandering back to Kenneth Koch's 'The Artist', a poem published in 1962 that foresaw much of what was to come in the art world, from Claes Oldenberg's gigantic Pop Art forms to Conceptual Art, by way of Land Art, Earthworks, site-specific environmental installations, etc.

The poem begins with the somewhat megalomaniac artist bidding farewell to one of his works:

'Ah well, I abandon you, cherrywood smokestack,

Near the entrance to this old green park!...'

Soon he is looking back fondly to one his early works –

'I often think Play was my best work.

It is an open field with a few boards in it.

Children are allowed to come and play in Play

By permission of the Cleveland Museum.'

Next he makes steel cigarettes for the Indianopolis Museum, but then he really gets going with Bee –

'Bee will be a sixty-yards-long covering for the elevator shaft opening in the foundry sub-basement

Near my home. So far it's white sailcloth with streams of golden paint evenly spaced out

With a small blue pond at one end, and around it orange and green flowers...'

But this project is soon dwarfed by the next one. A newspaper reports –

'The Magician of Cincinnati is now ready for human use. They are twenty-five tremendous stone staircases, each over six hundred feet high, which will be placed in the Ohio River between Cincinnati and Louisville, Kentucky. All the boats coming down the Ohio River will presumably be smashed up against the immense statues, which are the most recent work of the creator of Flowers, Bee, Play, Again and Human Use...'

The artist picks up the story –

'May 16th. With what an intense joy I watched the installation of The Magician of Cincinnati today, in the Ohio River, where it belongs, and which is so much part of my original scheme ...

May 17th. I feel suddenly freed from life – not so much as if my work were going to change, but as though I had at last seen what I had so long been prevented (perhaps I prevented myself!) from seeing: that there is too much for me to do. Somehow this enables me to relax, to breathe easily...'

The poem ends with the artist confronting his greatest creative challenge –

'June 3rd. It doesn't seem possible – the Pacific Ocean! I have ordered sixteen million tons of blue paint. Waiting anxiously for it to arrive. How would grass be as a substitute? Cement?'

Indeed. Why not? What limits can there possibly be to Art?

The poem begins with the somewhat megalomaniac artist bidding farewell to one of his works:

'Ah well, I abandon you, cherrywood smokestack,

Near the entrance to this old green park!...'

Soon he is looking back fondly to one his early works –

'I often think Play was my best work.

It is an open field with a few boards in it.

Children are allowed to come and play in Play

By permission of the Cleveland Museum.'

Next he makes steel cigarettes for the Indianopolis Museum, but then he really gets going with Bee –

'Bee will be a sixty-yards-long covering for the elevator shaft opening in the foundry sub-basement

Near my home. So far it's white sailcloth with streams of golden paint evenly spaced out

With a small blue pond at one end, and around it orange and green flowers...'

But this project is soon dwarfed by the next one. A newspaper reports –

'The Magician of Cincinnati is now ready for human use. They are twenty-five tremendous stone staircases, each over six hundred feet high, which will be placed in the Ohio River between Cincinnati and Louisville, Kentucky. All the boats coming down the Ohio River will presumably be smashed up against the immense statues, which are the most recent work of the creator of Flowers, Bee, Play, Again and Human Use...'

The artist picks up the story –

'May 16th. With what an intense joy I watched the installation of The Magician of Cincinnati today, in the Ohio River, where it belongs, and which is so much part of my original scheme ...

May 17th. I feel suddenly freed from life – not so much as if my work were going to change, but as though I had at last seen what I had so long been prevented (perhaps I prevented myself!) from seeing: that there is too much for me to do. Somehow this enables me to relax, to breathe easily...'

The poem ends with the artist confronting his greatest creative challenge –

'June 3rd. It doesn't seem possible – the Pacific Ocean! I have ordered sixteen million tons of blue paint. Waiting anxiously for it to arrive. How would grass be as a substitute? Cement?'

Indeed. Why not? What limits can there possibly be to Art?

June

A new week, a new month – and new hope that this disgraceful lockdown is beginning to ease, or at least to fray at the edges. It's become increasingly clear that it was never necessary, is quite probably counterproductive, and that the costs – in economic and social terms and in lives lost – will far outweigh any presumed benefits. Not that Boris Johnson had any choice but to impose it, such was the clamour at the time from the public, the media and 'The Science' (Boris's far too loud backing band). What still astonishes me, sentimental nostalgist that I am, is the eagerness with which the English people embraced a wholesale confiscation of their liberties unprecedented in peacetime – and many of them still seem to want it to go on and on and on... Happily others are busy releasing themselves from this bondage already, hence the perceptible fraying at the edges and the noticeably more relaxed atmosphere. The churches, however, remain firmly closed, locked and, to all intents and purposes, redundant. If the Church of England had set out to prove once and for all its complete irrelevance, it could hardly have done a better job. What it tells us about that institution is deeply depressing...

On the other hand, it's certainly been a spring to remember. The weather has been simply astonishing, at least here in the Southeast – all through April and May, day after day of unbroken sunshine. And the butterflies! I've never before seen so many Green Hairstreaks, Grizzled Skippers and Small Blues [below], and I've already spotted two species I wouldn't normally expect to see till well into June (Large Skipper and Meadow Brown). The 'lockdown' has kept me closer to home than usual, and as a result I've discovered lepidopteral riches in places I would not have looked before. Today, as the sun still shines, my plan is to go a little further afield to see what discoveries await me...

On the other hand, it's certainly been a spring to remember. The weather has been simply astonishing, at least here in the Southeast – all through April and May, day after day of unbroken sunshine. And the butterflies! I've never before seen so many Green Hairstreaks, Grizzled Skippers and Small Blues [below], and I've already spotted two species I wouldn't normally expect to see till well into June (Large Skipper and Meadow Brown). The 'lockdown' has kept me closer to home than usual, and as a result I've discovered lepidopteral riches in places I would not have looked before. Today, as the sun still shines, my plan is to go a little further afield to see what discoveries await me...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)