I was startled to learn that today is my second birthday on Facebook - I had no idea it was so long since I half-heartedly joined up to that epic time-waster (largely because The Dabbler had migrated there). My participation has been limited to putting up the odd photo, posting the occasional comment and 'liking' this and that, and I have no intention of going any farther...

Today is also the last of September, and I got Butterfly Conservation's Annual Review in the post, so clearly it is time for my own annual review of my butterfly year - which was, I have to say, a corker. I totted up more species than ever before, and in fact saw every one I could have hoped to find in my patch of Surrey suburbia on the edge of the North Downs chalkland (except the Purple Emperor and Clouded Yellow). I even had the added bonus of the reintroduced Glanville Fritillary. But essentially this was the Year of the Hairstreak, and I shall never forget my magical, wholly unlooked-for encounters with the elusive White-Letter Hairstreak (a fifty-year first for me) and the equally elusive Brown Hairstreak (a lifetime first). What a year!

Friday 30 September 2016

Thursday 29 September 2016

Remembering Passe-partout

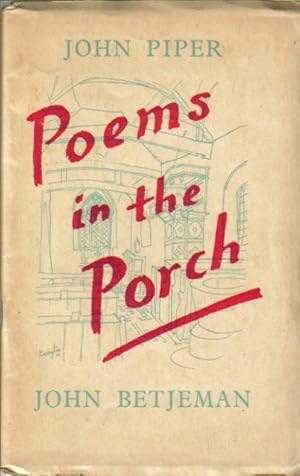

My latest charity-shop spot was this slim volume from 1954 - scarcely more than a pamphlet - of church poems by Betjeman, with delightful line drawings by John Piper. The Author's Note is characteristically self-effacing: 'These verses do not pretend to be poetry,' he begins. They were written, Betjeman explains, 'for speaking on the wireless', and 'in order to compensate for the shortcomings of the verse, I have prevailed on my friend Mr John Piper to provide the illustrations.'

The volume contains Septuagesima, Betjeman's love song to the dear old C of E ('The Church of England of my birth, The kindest church to me on Earth') and the ever popular Diary of a Church Mouse. One I hadn't read before was the mildly satirical Friends of the Cathedral, and in this I came across a phrase that gave me pause - 'The hundred little bits of script Each framed in passe-partout'. Framed in passe-partout? Passe-partout? Suddenly it came back to me...

You used to see it everywhere. Passe-partout was a kind of tough adhesive tape, typically black with a slightly grainy texture, that had a variety of uses but was particularly popular as a cheap form of picture-framing - just run the tape carefully around the edges, pressing picture, glass and backing board together, leave to set, and you had the semblance of a framed picture at negligible cost. My father was keen on the stuff, I remember - this before he discovered the thousand and one uses to which Fablon could be put - and there were pictures framed in passe-partout all over the house. It was not pretty, but it did the job, just about.

The stuff is no longer manufactured, but it still has its devotees. You can buy vintage rolls of passe-partout on eBay ('Butterfly Brand', with the stylised Camberwell Beauty trade mark), and there is even - you will not be surprised to learn - a blog devoted to the wonders of passe-partout. Don't you just love the internet?

The volume contains Septuagesima, Betjeman's love song to the dear old C of E ('The Church of England of my birth, The kindest church to me on Earth') and the ever popular Diary of a Church Mouse. One I hadn't read before was the mildly satirical Friends of the Cathedral, and in this I came across a phrase that gave me pause - 'The hundred little bits of script Each framed in passe-partout'. Framed in passe-partout? Passe-partout? Suddenly it came back to me...

You used to see it everywhere. Passe-partout was a kind of tough adhesive tape, typically black with a slightly grainy texture, that had a variety of uses but was particularly popular as a cheap form of picture-framing - just run the tape carefully around the edges, pressing picture, glass and backing board together, leave to set, and you had the semblance of a framed picture at negligible cost. My father was keen on the stuff, I remember - this before he discovered the thousand and one uses to which Fablon could be put - and there were pictures framed in passe-partout all over the house. It was not pretty, but it did the job, just about.

The stuff is no longer manufactured, but it still has its devotees. You can buy vintage rolls of passe-partout on eBay ('Butterfly Brand', with the stylised Camberwell Beauty trade mark), and there is even - you will not be surprised to learn - a blog devoted to the wonders of passe-partout. Don't you just love the internet?

Tuesday 27 September 2016

One More

One effect of visiting an art-rich city like Venice over a span of years - decades indeed - is that you get to notice how your taste changes over time. Mine has certainly widened to include much more Venetian 18th-century painting (especially the Tiepolos and Piazzetta), which I used to regard as essentially frivolous and sketchy. How wrong I was...

On this visit, looking round the beautifully sited Peggy Guggenheim collection for the first time in many years, I realised that my taste in modern art had changed as well. Whereas before I had marvelled at the pioneering early-20th-century work of the Cubists, Surrealists and even Futurists and had been left cold by the Abstract Expressionists, I now found, to my surprise, that these responses had been reversed. Much of the early-20th-century stuff now seemed dry, lifeless, even academic - whereas the small collection of Abstract Expressionists stirred me as never before. In particular Jackson Pollock's vast Alchemy now speaks - or sings - to me, and I found it hard to tear myself away from the beautiful early Willem de Kooning (Untitled, 1958). Clearly I have changed, or my taste has.

However, the division was not that clear-cut, as at least three of the early-20th-century paintings caught my eye: a magical 1911 Chagall, La Pluie, and two wonderful Klees, Magic Garden (1926) [below] and Portrait of Frau P in the South (1924) [above], neither of which reproduces very well.

But enough - basta.

On this visit, looking round the beautifully sited Peggy Guggenheim collection for the first time in many years, I realised that my taste in modern art had changed as well. Whereas before I had marvelled at the pioneering early-20th-century work of the Cubists, Surrealists and even Futurists and had been left cold by the Abstract Expressionists, I now found, to my surprise, that these responses had been reversed. Much of the early-20th-century stuff now seemed dry, lifeless, even academic - whereas the small collection of Abstract Expressionists stirred me as never before. In particular Jackson Pollock's vast Alchemy now speaks - or sings - to me, and I found it hard to tear myself away from the beautiful early Willem de Kooning (Untitled, 1958). Clearly I have changed, or my taste has.

However, the division was not that clear-cut, as at least three of the early-20th-century paintings caught my eye: a magical 1911 Chagall, La Pluie, and two wonderful Klees, Magic Garden (1926) [below] and Portrait of Frau P in the South (1924) [above], neither of which reproduces very well.

But enough - basta.

Monday 26 September 2016

More...

Above is the view from my hotel room, looking over to the Giudecca and Palladio's Redentore, the most intellectually rigorous of his Venetian churches, a brilliant exercise in pure architecture. Oddly the façade - one that repays endless contemplation - looks better close up than it does from across the canal. Which is a pity, in view of its location...

And below is the same view obscured by one of the monstrous cruise liners that sail into Venice every day to tie up and disgorge their thousands of day trippers into the clogged streets around San Marco.

These gigantic floating hotels are extremely unpopular with the locals. Stickers and banners proclaiming 'NO Grandi Navi' are everywhere in the city, and on the day we left a big demonstration against them was just getting under way. The administration, however, having effectively bankrupted the city, has little choice but to encourage anything that brings in money. A sad state of affairs, but such is the resilience of Venice and the Venetians that you feel they will somehow survive and thrive, come what may.

And below is the same view obscured by one of the monstrous cruise liners that sail into Venice every day to tie up and disgorge their thousands of day trippers into the clogged streets around San Marco.

These gigantic floating hotels are extremely unpopular with the locals. Stickers and banners proclaiming 'NO Grandi Navi' are everywhere in the city, and on the day we left a big demonstration against them was just getting under way. The administration, however, having effectively bankrupted the city, has little choice but to encourage anything that brings in money. A sad state of affairs, but such is the resilience of Venice and the Venetians that you feel they will somehow survive and thrive, come what may.

Venice Notes

Well, the week in Venice was wonderful (what else could it be?) - and there were even butterflies: tiny Long-Tailed Blues were flying everywhere, along with more familiar Red Admirals and Commas. I had the most satisfying tour of San Marco I've ever had, thanks to the excellent queue-jumping system and the fact that the balcony overlooking the Piazza was open. The glittering mosaics inside never looked better - I'm sure they've improved the lighting since my last visit - and the crowds were at quite bearable levels.

There were also things I was experiencing for the first time (in getting on for 50 years of visits to Venice), including a visit to the cemetery island of San Michele. The more recent parts feel very much like warehousing for the dead, who are mostly represented only by tablets (with photographic portrait and tribute of artificial flowers) arranged over every surface of numerous massive slab-like blocks. It is, if nothing else, a potent reminder that the vast majority of us humans are dead. However, the older and less crowded parts of the cemetery are more atmospheric, and in the Russian/Greek section are the graves of Igor and Vera Stravinsky (two large but plain horizontal slabs) and that of Diaghilev, a grander affair, touchingly hung with votive offerings of ballet pumps.

Also on San Michele, hidden away in the Protestant section, is the remarkably unostentatious grave of Ezra Pound - a small incised tablet in danger of being overgrown by vegetation, but still evidently attracting the odd floral tribute. (Somewhere among the Protestants, too, is the grave of Joseph Brodsky, but we weren't able to find that one.)

Another Venice first for me was a visit to the Palazzo Fortuny, home of the great textile designer whose dresses were made of such fine silks that it was said you could pass one through a wedding ring. Naturally I was expecting a display of gorgeous textiles and dresses - but alas, the Palazzo, when we eventually found it, had been taken over by an extravagant display of the Contemporary Yarts at their most tiresome, including a massively dreary installation devoted to stirring our consciences over Syria and such. I was neither stirred nor shaken.

Elsewhere some Fortuny textiles were indeed present, but hung in dim light and mostly behind works of Contemporary Yart, or indeed behind the so-so paintings of Fortuny himself. Whether it was just bad luck to find such a state of affairs at the Palazzo Fortuny I do not know, but it was certainly a sad disappointment.

And then there was the Acqua Alta bookshop, which I didn't even know existed but just happened to spot as we were walking past. This is up there among the most eccentric, not to say mad, second-hand bookshops I have ever come across, in parts less like a bookshop than some kind of junkyard. However, despite appearances, many of the shelves are actually quite well organised - which is more than you can say for some bookshops I've known. The impression of chaos, however, prevails - especially when the dishevelled proprietor is wandering about the premises, cigarette in gesticulating hand, talking apparently to himself in a voice raspingly harsh and guttural even by Venetian standards (which is saying something). There's more about Acqua Alta - which has quite a cult following - here.

And there will be more about Venice here in my next post...

There were also things I was experiencing for the first time (in getting on for 50 years of visits to Venice), including a visit to the cemetery island of San Michele. The more recent parts feel very much like warehousing for the dead, who are mostly represented only by tablets (with photographic portrait and tribute of artificial flowers) arranged over every surface of numerous massive slab-like blocks. It is, if nothing else, a potent reminder that the vast majority of us humans are dead. However, the older and less crowded parts of the cemetery are more atmospheric, and in the Russian/Greek section are the graves of Igor and Vera Stravinsky (two large but plain horizontal slabs) and that of Diaghilev, a grander affair, touchingly hung with votive offerings of ballet pumps.

Also on San Michele, hidden away in the Protestant section, is the remarkably unostentatious grave of Ezra Pound - a small incised tablet in danger of being overgrown by vegetation, but still evidently attracting the odd floral tribute. (Somewhere among the Protestants, too, is the grave of Joseph Brodsky, but we weren't able to find that one.)

Another Venice first for me was a visit to the Palazzo Fortuny, home of the great textile designer whose dresses were made of such fine silks that it was said you could pass one through a wedding ring. Naturally I was expecting a display of gorgeous textiles and dresses - but alas, the Palazzo, when we eventually found it, had been taken over by an extravagant display of the Contemporary Yarts at their most tiresome, including a massively dreary installation devoted to stirring our consciences over Syria and such. I was neither stirred nor shaken.

Elsewhere some Fortuny textiles were indeed present, but hung in dim light and mostly behind works of Contemporary Yart, or indeed behind the so-so paintings of Fortuny himself. Whether it was just bad luck to find such a state of affairs at the Palazzo Fortuny I do not know, but it was certainly a sad disappointment.

And then there was the Acqua Alta bookshop, which I didn't even know existed but just happened to spot as we were walking past. This is up there among the most eccentric, not to say mad, second-hand bookshops I have ever come across, in parts less like a bookshop than some kind of junkyard. However, despite appearances, many of the shelves are actually quite well organised - which is more than you can say for some bookshops I've known. The impression of chaos, however, prevails - especially when the dishevelled proprietor is wandering about the premises, cigarette in gesticulating hand, talking apparently to himself in a voice raspingly harsh and guttural even by Venetian standards (which is saying something). There's more about Acqua Alta - which has quite a cult following - here.

And there will be more about Venice here in my next post...

Sunday 18 September 2016

Shoes

Enough of stinkpipes - tomorrow I'm off to Venice for a week of aesthetic overload in the most beautiful city on Earth. Unfortunately my best strolling shoes came apart at the seams the other day, so I was obliged to look for another pair - Venice is a city that demands stout footwear.

It was not easy to find anything at all in my size (it never is, not since Clowns R Us closed down), and I was on the point of giving up when I happened on a shoe shop called Deichmann - a new one on me, German I believe. There, finally, I found a pair of shoes of acceptable design in my size - perfect. And the brand name of those shoes was (drumroll, please) Venice.

I have my Venice shoes.

It was not easy to find anything at all in my size (it never is, not since Clowns R Us closed down), and I was on the point of giving up when I happened on a shoe shop called Deichmann - a new one on me, German I believe. There, finally, I found a pair of shoes of acceptable design in my size - perfect. And the brand name of those shoes was (drumroll, please) Venice.

I have my Venice shoes.

Friday 16 September 2016

Stinkpipe Days

Reading this interesting piece on London's lost rivers (which has been shared on The Dabbler), I was intrigued to come across the phrase 'Victorian stink pipes'. It took me back (like a rather less fragrant madeleine dunked in linden tea) to the autumn of 1959, when I arrived from Ealing, the alleged 'queen of suburbs', at my new home in the Surrey suburban demiparadise of Carshalton. Here was a streetscape - and water-woven parkscape - notably unlike what I had been used to, and it had its mystifying features.

Among these were the tall, green-painted cast-iron columns that decorated so many streets. A number of these had ornate crowns, some with wind vanes, some with three or four trumpet-shaped openings. What on earth were they, and what were they for? None of my schoolfriends seemed to know, but there was a quite plausible theory that during the war they had housed air-raid sirens. Gradually I began to realise that they must in fact be some kind of ventilation system, presumably for sewers or underground rivers - but by then they were mysteriously disappearing anyway (I never saw one being taken down). Now I know just what they are/were - 'stinkpipes', aka 'stenchpipes', both good no-nonsense names which we schoolboys would have relished had we known them. They are so popular there is even a blog devoted to the stinkpipes of London.

Pictured above is a surviving ornate stinkpipe just down the road from where I live.

Among these were the tall, green-painted cast-iron columns that decorated so many streets. A number of these had ornate crowns, some with wind vanes, some with three or four trumpet-shaped openings. What on earth were they, and what were they for? None of my schoolfriends seemed to know, but there was a quite plausible theory that during the war they had housed air-raid sirens. Gradually I began to realise that they must in fact be some kind of ventilation system, presumably for sewers or underground rivers - but by then they were mysteriously disappearing anyway (I never saw one being taken down). Now I know just what they are/were - 'stinkpipes', aka 'stenchpipes', both good no-nonsense names which we schoolboys would have relished had we known them. They are so popular there is even a blog devoted to the stinkpipes of London.

Pictured above is a surviving ornate stinkpipe just down the road from where I live.

Thursday 15 September 2016

From Waterside to Mainstream

My admiration for David Attenborough has, I must admit, faded considerably in recent years - too much substandard work (excusable at his age, of course), too many dubious public pronouncements. However, Sir David can still come good - as his latest excursion into radio, The Waterside Ape, proves. A Radio 4 two-parter, which ended today (available on the BBC iPlayer), this explored the 'aquatic ape theory' - that much of what makes us human evolved not on the open savannah but by the waterside - and brought us up to date with the latest findings. I've always been attracted to this hypothesis, for which there is ever more compelling evidence, and I was glad to discover that what was once dismissed as cranky pseudoscience has now entered the mainstream, many of the keenest proponents of the (exclusive) savannah theory having admitted that it was never that simple and that an aquatic phase was crucial to human development (growing our brains and making speech possible, among other things).

It took a long time for the aquatic ape theory to be taken seriously because it first came to public notice in a bestselling book, The Descent of Woman (1972), by a non-scientist, the screenwriter Elaine Morgan. Though she followed it up with more rigorously scientific treatments of the theme, very few in the science community were taking any notice.

Elaine Morgan was first alerted to the aquatic hypothesis by a passing reference in a book by Savannah man Desmond Morris, who directed her to the eminent marine biologist Alister Hardy. As long ago as 1930, Hardy had begun to think that there must have been an aquatic phase in human evolution, but he had kept mum for 30 years. As he frankly admitted, he was still young when the idea struck him and he wanted to build a glittering career within the scientific establishment; if he had published a paper on such a wildly heterodox theory, his career would have been over.

How's that for an eloquent statement of How Science Works (and how it worked even back in the 1930s)? Whatever science might be in theory, in practice it is decidedly prone to 'groupthink' and devotes huge resources to buttressing orthodoxies rather than opening them up to heterodox thinking. With the practice of science heavily dependent on research grants, it is all too easy for scientists to play it safe, proposing work that pushes an established line of research a little further along a beaten path, will duly be published in the appropriate peer-reviewed way, and will swell the CV and sustain the career. This only encourages the strengthening of orthodox ways of thinking, to the point where it is almost impossible for scientists working within the system to overthrow the received wisdom. Yes, it can happen - as it eventually did, for example, with the received wisdom on stomach ulcers - but it usually takes a maverick with little to lose to take on the might of 'settled' science (not to mention, in the stomach ulcer case, the pharmaceutical industry).

It's good to know that the 'maverick' aquatic ape theory finally proved so strong that it is now widely accepted. Let's hope future TV series re-creating the lives of our hairy, bone-crunching forefathers take a break from the obligatory savannah hunting scenes and show us a bit of the lacustrine good life.

It took a long time for the aquatic ape theory to be taken seriously because it first came to public notice in a bestselling book, The Descent of Woman (1972), by a non-scientist, the screenwriter Elaine Morgan. Though she followed it up with more rigorously scientific treatments of the theme, very few in the science community were taking any notice.

Elaine Morgan was first alerted to the aquatic hypothesis by a passing reference in a book by Savannah man Desmond Morris, who directed her to the eminent marine biologist Alister Hardy. As long ago as 1930, Hardy had begun to think that there must have been an aquatic phase in human evolution, but he had kept mum for 30 years. As he frankly admitted, he was still young when the idea struck him and he wanted to build a glittering career within the scientific establishment; if he had published a paper on such a wildly heterodox theory, his career would have been over.

How's that for an eloquent statement of How Science Works (and how it worked even back in the 1930s)? Whatever science might be in theory, in practice it is decidedly prone to 'groupthink' and devotes huge resources to buttressing orthodoxies rather than opening them up to heterodox thinking. With the practice of science heavily dependent on research grants, it is all too easy for scientists to play it safe, proposing work that pushes an established line of research a little further along a beaten path, will duly be published in the appropriate peer-reviewed way, and will swell the CV and sustain the career. This only encourages the strengthening of orthodox ways of thinking, to the point where it is almost impossible for scientists working within the system to overthrow the received wisdom. Yes, it can happen - as it eventually did, for example, with the received wisdom on stomach ulcers - but it usually takes a maverick with little to lose to take on the might of 'settled' science (not to mention, in the stomach ulcer case, the pharmaceutical industry).

It's good to know that the 'maverick' aquatic ape theory finally proved so strong that it is now widely accepted. Let's hope future TV series re-creating the lives of our hairy, bone-crunching forefathers take a break from the obligatory savannah hunting scenes and show us a bit of the lacustrine good life.

Tuesday 13 September 2016

The Gaiety of Nations

This afternoon, stupefied by the hottest September day of my lifetime, I was half-listening to Radio 4's Word of Mouth. This is an often interesting programme about words, devised years ago by its then presenter Frank Delaney (anyone remember him?), and subsequently presented for years by Michael Rosen. These days, however, Rosen has been joined by Dr Laura Wright, a linguist who apparently knows everything and delights in undermining and mildly humiliating Rosen at every turn. Rosen takes it all manfully but is clearly seething, and the tension between the two presenters makes a compelling little background psychodrama. Rosen has his moments though: he recently dumbfounded all present with a little anecdote about the charmless (to put it mildly) behaviour of the ghastly Roald Dahl towards his (Rosen's) son. It's the Dahl centenary today, I believe. No celebrations here.

But I digress. I was listening, as I say, to Word of Mouth when the phrase 'the gaiety of nations' came up, with someone remarking that the modern meaning of the adjective 'gay' hasn't carried over to the noun. But what of the phrase 'the gaiety of nations'? I was hoping someone would tell us where it originated, as I didn't know - maybe another one of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's, along with 'the great unwashed' and 'the pen is mightier than the sword'? No, it is actually a phrase of Samuel Johnson's, from his tribute to his friend and former pupil, the great actor David Garrick: 'I am disappointed by the stroke of death which has eclipsed the gaiety of nations and impoverished the public stock of harmless pleasure.' There is a version of it on Garrick's monument in Lichfield Cathedral, where I no doubt read it on my visit last year. It is a fine phrase, 'the gaiety of nations', as is 'the public stock of harmless pleasure'.

Lord, this heat...

But I digress. I was listening, as I say, to Word of Mouth when the phrase 'the gaiety of nations' came up, with someone remarking that the modern meaning of the adjective 'gay' hasn't carried over to the noun. But what of the phrase 'the gaiety of nations'? I was hoping someone would tell us where it originated, as I didn't know - maybe another one of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's, along with 'the great unwashed' and 'the pen is mightier than the sword'? No, it is actually a phrase of Samuel Johnson's, from his tribute to his friend and former pupil, the great actor David Garrick: 'I am disappointed by the stroke of death which has eclipsed the gaiety of nations and impoverished the public stock of harmless pleasure.' There is a version of it on Garrick's monument in Lichfield Cathedral, where I no doubt read it on my visit last year. It is a fine phrase, 'the gaiety of nations', as is 'the public stock of harmless pleasure'.

Lord, this heat...

Monday 12 September 2016

Festival Time

For the first time, my visit to Wirksworth (my spiritual second home in Derbyshire) coincided with the Wirksworth Festival - specifically with the weekend in which, among many other activities, more than 60 houses and public buildings are given over to the display of arts and crafts.

Generally speaking, I'm no fan of arts festivals (I managed to entirely avoid the Edinburgh Festival while living in that city for a year) - but Wirksworth is different. With very little funding but huge reserves of community spirit and an extraordinary concentration of creative work going on all the time in the town, Wirksworth manages to create something very special and quite unlike other festivals. The key to its unique appeal is, I think, that so much of the art is displayed in people's homes - either the artists' own or those of other townspeople happy to join in.

There's always simple pleasure to be had in seeing inside other people's homes, and a very high proportion of the houses in Wirksworth are interesting in themselves, and often beautifully laid-out inside. There are some delightful town gardens too - all there for all to enjoy, along with the art, for the duration of the weekend. Making even a highly selective tour with my cousin - a long-time resident who is on friendly greeting terms with le tout Wirksworth and their dogs (it's a very doggy town) - was slow progress, but all the more enjoyable for that. This is a genuinely local, genuinely friendly event, in which truly the whole town is involved and which the whole town seems to enjoy.

The artists displaying their work included not only well established practitioners who've been around a while but also, happily, an up-and-coming new generation. The artists who poured into Wirksworth back when it was a run-down post-industrial town not only transformed the nature of the place but created something that looks set to run and run - as, surely, will the festival.

The centrepiece of this year's festival is an installation in the parish church by Wolfgang Buttress, no less, the artist responsible for the hugely successful Hive, currently pulling them in at Kew. It was quite a coup to get him for Wirksworth, and BEAM, his work in the church, is impressive - a reflective, light-spangled, music-bedded presence projecting a series of changing images onto the crossing roof. You can hear him talking about it here. The pictures above and below are my own, and do it scant justice.

Generally speaking, I'm no fan of arts festivals (I managed to entirely avoid the Edinburgh Festival while living in that city for a year) - but Wirksworth is different. With very little funding but huge reserves of community spirit and an extraordinary concentration of creative work going on all the time in the town, Wirksworth manages to create something very special and quite unlike other festivals. The key to its unique appeal is, I think, that so much of the art is displayed in people's homes - either the artists' own or those of other townspeople happy to join in.

There's always simple pleasure to be had in seeing inside other people's homes, and a very high proportion of the houses in Wirksworth are interesting in themselves, and often beautifully laid-out inside. There are some delightful town gardens too - all there for all to enjoy, along with the art, for the duration of the weekend. Making even a highly selective tour with my cousin - a long-time resident who is on friendly greeting terms with le tout Wirksworth and their dogs (it's a very doggy town) - was slow progress, but all the more enjoyable for that. This is a genuinely local, genuinely friendly event, in which truly the whole town is involved and which the whole town seems to enjoy.

The artists displaying their work included not only well established practitioners who've been around a while but also, happily, an up-and-coming new generation. The artists who poured into Wirksworth back when it was a run-down post-industrial town not only transformed the nature of the place but created something that looks set to run and run - as, surely, will the festival.

The centrepiece of this year's festival is an installation in the parish church by Wolfgang Buttress, no less, the artist responsible for the hugely successful Hive, currently pulling them in at Kew. It was quite a coup to get him for Wirksworth, and BEAM, his work in the church, is impressive - a reflective, light-spangled, music-bedded presence projecting a series of changing images onto the crossing roof. You can hear him talking about it here. The pictures above and below are my own, and do it scant justice.

Saturday 10 September 2016

A Strelley Tomb

When Philip Larkin came upon the Arundel tomb in Chichester Cathedral that inspired one of his most famous poems he had, he says, never come across one like it - one in which the noble husband and wife are holding hands. If he had happened to be church-crawling in Nottinghamshire, he might have come across this equally touching double effigy and gifted the world A Strelley Tomb.

The tomb of Sir Sampson de Strelley and Elizabeth, his wife - the founders of All Saints Church, Strelley - stands in a glorious 14th-century chancel, separated from the nave by a beautiful coved rood screen that has survived in immaculate condition because for centuries it was boarded over. Sir Sampson and his lady have the traditional lion and dog at their feet; she wears an elaborate and 'almost unique' headpiece, while his helmeted head rests peacefully on that of a strangled Saracen (the family crest). Those joined hands are more prominent than the Arundel hands, standing proud of the two figures and being visible the length of the nave, blazoning the stone fidelity they hardly meant.

Larkin's poem is an old chestnut, beloved of readers keen to seize on a 'message' Larkin is of course far too careful and conflicted ever to deliver: 'What will survive of us is love'. No more than a half-proof of an 'almost-instinct', this is hardly a ringing affirmation - and yet Larkin is full aware of its force. And yet, and yet...

Oh it is such a good poem, even a great poem - let's have it one more time:

The tomb of Sir Sampson de Strelley and Elizabeth, his wife - the founders of All Saints Church, Strelley - stands in a glorious 14th-century chancel, separated from the nave by a beautiful coved rood screen that has survived in immaculate condition because for centuries it was boarded over. Sir Sampson and his lady have the traditional lion and dog at their feet; she wears an elaborate and 'almost unique' headpiece, while his helmeted head rests peacefully on that of a strangled Saracen (the family crest). Those joined hands are more prominent than the Arundel hands, standing proud of the two figures and being visible the length of the nave, blazoning the stone fidelity they hardly meant.

Larkin's poem is an old chestnut, beloved of readers keen to seize on a 'message' Larkin is of course far too careful and conflicted ever to deliver: 'What will survive of us is love'. No more than a half-proof of an 'almost-instinct', this is hardly a ringing affirmation - and yet Larkin is full aware of its force. And yet, and yet...

Oh it is such a good poem, even a great poem - let's have it one more time:

Side by side, their faces blurred,

The earl and countess lie in stone,

Their proper habits vaguely shown

As jointed armour, stiffened pleat,

And that faint hint of the absurd—

The little dogs under their feet.

Such plainness of the pre-baroque

Hardly involves the eye, until

It meets his left-hand gauntlet, still

Clasped empty in the other; and

One sees, with a sharp tender shock,

His hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

They would not think to lie so long.

Such faithfulness in effigy

Was just a detail friends would see:

A sculptor’s sweet commissioned grace

Thrown off in helping to prolong

The Latin names around the base.

They would not guess how early in

Their supine stationary voyage

The air would change to soundless damage,

Turn the old tenantry away;

How soon succeeding eyes begin

To look, not read. Rigidly they

Persisted, linked, through lengths and breadths

Of time. Snow fell, undated. Light

Each summer thronged the glass. A bright

Litter of birdcalls strewed the same

Bone-riddled ground. And up the paths

The endless altered people came,

Washing at their identity.

Now, helpless in the hollow of

An unarmorial age, a trough

Of smoke in slow suspended skeins

Above their scrap of history,

Only an attitude remains:

Time has transfigured them into

Untruth. The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be

Their final blazon, and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

Wednesday 7 September 2016

Madland Latest

Heaven knows, the wonderful world of TV adland has given us all some nasty jolts over the years -part of me is still reeling from this example of musical madvertising at its maddest - but when I first caught Cream's I Feel Free playing under (or rather over) an ad for some kind of broadband device, it was a shaker. They wouldn't - would they? Yes, of course they would - heck, the song's about someone feeling free, just like they do with this broadband thingy. Simples.

It was 50 years ago when Cream's album Disraeli Gears came out, I was but a suburban schoolboy in his GCE year, but that album sounded to me like something from another world - a world in which I immediately set out to immerse myself, with (ahem) mixed results. If anyone had told me then that the stand-out track of that album would end up being used on a TV ad, what would I have said, what would I have thought? Ah, it all seemed so real back then. It would appear we have failed to keep it real, never mind paint it black.

I'm off to the open spaces of the Peak District tomorrow for a few days - cue chorus of 'I-i-i Fe-el Free'...

It was 50 years ago when Cream's album Disraeli Gears came out, I was but a suburban schoolboy in his GCE year, but that album sounded to me like something from another world - a world in which I immediately set out to immerse myself, with (ahem) mixed results. If anyone had told me then that the stand-out track of that album would end up being used on a TV ad, what would I have said, what would I have thought? Ah, it all seemed so real back then. It would appear we have failed to keep it real, never mind paint it black.

I'm off to the open spaces of the Peak District tomorrow for a few days - cue chorus of 'I-i-i Fe-el Free'...

Tuesday 6 September 2016

'I have followed my own tastes as they are now and as they were in my childhood...'

The other day, at a local fair, Mrs Nige spotted a slender volume with the unpromising title Favourite Verse. Equally unpromising was the dust-jacket photograph of a clump of primroses - but under the title was the very much more promising line 'Edited by Stevie Smith'.

The book has a curious history, having originally been published (in 1970, the year before Stevie Smith's death) as The Batsford Book of Children's Verse. As such, it would have constituted one of the most eccentric children's anthologies ever. The title of the reissue, Favourite Verse, is very much more descriptive. As the Bard of Palmers Green says in her preface, 'In selecting verses for this book I have followed my own tastes as they are now and as they were in my childhood.' So it is a highly personal, not entirely child-oriented selection - and a fascinating one.

A good many old favourites - mostly from Shakespeare and the Romantic poets - are there, but Stevie Smith casts her net wide, including traditional ballads and passages from the Old Testament among her selections. She is happy, too, to include five of her own poems (The Old Sweet Dove of Wiveton, The Frog Prince, Hymn to the Seal, So to Fatness Come and The Occasional Yarrow). There is a good sprinkling of American poets, from Longfellow to Robert Frost (Acquainted with the Night), with a bit of Whitman ('I think I could turn and live with animals...') - but, oddly, not a line of Emily Dickinson.

Purchasers of The Batsford Book of Children's Verse must have been startled to find, on the very first page, these red-blooded lines from Matthew Arnold's The Strayed Reveller -

These things, Ulysses,

The wise Bards also

Behold and sing.

But oh, what labour!

O Prince, what pain!

They too can see

Tiresias:--but the Gods,

Who give them vision,

Added this law:

That they should bear too

His groping blindness,

His dark foreboding,

His scorn'd white hairs;

Bear Hera's anger

Through a life lengthen'd

To seven ages.

They see the Centaurs

On Pelion:--then they feel,

They too, the maddening wine

Swell their large veins to bursting: in wild pain

They feel the biting spears

Of the grim Lapithae, and Theseus, drive,

Drive crashing through their bones: they feel

High on a jutting rock in the red stream

Alcmena's dreadful son

Ply his bow:--such a price

The Gods exact for song;

To become what we sing.

Within the next few pages, we find Coleridge's Catullan Hendecasyllables (of all things), a passage from Shelley's The Masque of Anarchy (the first of two), and Robert Southwell's The Burning Babe. There's even some Crashaw later on (an excerpt from The Office of the Holy Cross) - and Hardy is represented by the wonderfully sardonic The Ruined Maid. Yes, this is very much Stevie Smith's Favourite Verse.

In her preface, she tell us that the first poem she ever learnt by heart was Shelley's Arethusa (the poem woozily quoted by Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday). That was perhaps a strange place to start, but then Stevie was clearly an unusual child:

'Childhood thoughts can cut deep [she writes]. I remember when I was about eight, for instance, thinking the road ahead might be rather too long, and being cheered by the thought, at that moment first occurring to me, that life lay in our hands. Many poems have been inspired by this thought, at least many of mine have.'

Footnote: Stevie Smith fulfilled another commission for Batsford in 1959, supplying the introduction and picture captions for a volume called Cats in Colour. I'll keep an eye open for that - though I don't suppose it will be quite as rewarding as her Favourite Verse.

The book has a curious history, having originally been published (in 1970, the year before Stevie Smith's death) as The Batsford Book of Children's Verse. As such, it would have constituted one of the most eccentric children's anthologies ever. The title of the reissue, Favourite Verse, is very much more descriptive. As the Bard of Palmers Green says in her preface, 'In selecting verses for this book I have followed my own tastes as they are now and as they were in my childhood.' So it is a highly personal, not entirely child-oriented selection - and a fascinating one.

A good many old favourites - mostly from Shakespeare and the Romantic poets - are there, but Stevie Smith casts her net wide, including traditional ballads and passages from the Old Testament among her selections. She is happy, too, to include five of her own poems (The Old Sweet Dove of Wiveton, The Frog Prince, Hymn to the Seal, So to Fatness Come and The Occasional Yarrow). There is a good sprinkling of American poets, from Longfellow to Robert Frost (Acquainted with the Night), with a bit of Whitman ('I think I could turn and live with animals...') - but, oddly, not a line of Emily Dickinson.

Purchasers of The Batsford Book of Children's Verse must have been startled to find, on the very first page, these red-blooded lines from Matthew Arnold's The Strayed Reveller -

Within the next few pages, we find Coleridge's Catullan Hendecasyllables (of all things), a passage from Shelley's The Masque of Anarchy (the first of two), and Robert Southwell's The Burning Babe. There's even some Crashaw later on (an excerpt from The Office of the Holy Cross) - and Hardy is represented by the wonderfully sardonic The Ruined Maid. Yes, this is very much Stevie Smith's Favourite Verse.

In her preface, she tell us that the first poem she ever learnt by heart was Shelley's Arethusa (the poem woozily quoted by Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday). That was perhaps a strange place to start, but then Stevie was clearly an unusual child:

'Childhood thoughts can cut deep [she writes]. I remember when I was about eight, for instance, thinking the road ahead might be rather too long, and being cheered by the thought, at that moment first occurring to me, that life lay in our hands. Many poems have been inspired by this thought, at least many of mine have.'

Footnote: Stevie Smith fulfilled another commission for Batsford in 1959, supplying the introduction and picture captions for a volume called Cats in Colour. I'll keep an eye open for that - though I don't suppose it will be quite as rewarding as her Favourite Verse.

Sunday 4 September 2016

Sunday Morning Music

Here's a rather lovely little piece of music for Sunday morning...

It's one of the few surviving works by the Norwegian composer and violin virtuoso Ole Bull. After a shaky start ('After living for a while in Germany, where he pretended to study law,' says Wikipdeia, 'he went to Paris but fared badly for a year or two'), Bull built a hugely successful international concert career, playing 274 concerts in England in the year 1837 alone. Along the way, he gave the young Edvard Grieg - Bull's brother was married to Grieg's aunt - a helping hand, and played his part in asserting Norwegian national identity and independence.

Bull had a huge success in America too, and in 1852 bought a tract of land in Pennsylvania, meaning to establish a Norwegian colony, New Norway, with his own castle built on the highest point. The castle was never completed and the whole project eventually failed. The land is now the site of Ole Bull State Park. Towards the end of his life, Bull bought an island south of Bergen and built a palatial villa there (that's a view of the courtyard below), in which he died in 1880.

It's one of the few surviving works by the Norwegian composer and violin virtuoso Ole Bull. After a shaky start ('After living for a while in Germany, where he pretended to study law,' says Wikipdeia, 'he went to Paris but fared badly for a year or two'), Bull built a hugely successful international concert career, playing 274 concerts in England in the year 1837 alone. Along the way, he gave the young Edvard Grieg - Bull's brother was married to Grieg's aunt - a helping hand, and played his part in asserting Norwegian national identity and independence.

Bull had a huge success in America too, and in 1852 bought a tract of land in Pennsylvania, meaning to establish a Norwegian colony, New Norway, with his own castle built on the highest point. The castle was never completed and the whole project eventually failed. The land is now the site of Ole Bull State Park. Towards the end of his life, Bull bought an island south of Bergen and built a palatial villa there (that's a view of the courtyard below), in which he died in 1880.

Saturday 3 September 2016

The Day War Broke Out

Seventy-seven years ago today, the nation found itself at war with Nazi Germany. It was a gloriously sunny Sunday morning when Chamberlain made his famous broadcast confirming the sorry fact. Three years earlier, a film of H.G. Wells's The Shape of Things to Come had shown his predicted war beginning with waves of bombers immediately appearing and dropping gas bombs onto a helpless population. This horrific scenario had lingered in the popular imagination and it was widely expected that something of the sort would play out in the skies over England. When air-raid sirens began to sound in London shortly after the declaration of war, many feared that events were about to unfold along the lines predicted by Wells. Many others, however, being English, remained calm, suspecting that this was most likely a false alarm. And so it was. What's more, the feared 'gas bombs' were never employed against this country. As so often before and since, the new war was being envisaged in terms of the previous one - even by the supposed futurologist Wells.

In a typically English process of deflation, 'the day war broke out' was soon to become a comic catchphrase.

In a typically English process of deflation, 'the day war broke out' was soon to become a comic catchphrase.

Friday 2 September 2016

A Stone

This afternoon I was walking (with my walking friends) in the alien air of North London, where I always feel like a stranger in a strange land, dyed-in-the-wool South Londoner that I am. I realised that I probably hadn't been in hilly Highgate for 40 years or more, and yes Highgate Village is indeed very lovely in its North London way. I missed morning visits to St Stephen, Rosslyn Hill (Teulon) and St Jude (Lutyens) but got to stand with due reverence (not unmingled with indifference) outside a couple of monuments to modernism - the Goldfinger house on Willow Road and the Isokon Flats on Lawn Road (which look strangely like an Osbert Lancaster drawing).

Along the way I took the photograph above, of the Stone of Free Speech on Parliament Hill. Nobody seems to know the history of this stone bollard, but it has somehow acquired a reputation as a place where free speech is protected - which can only be a good thing in these censorious times. Modern 'pagans' seem to like holding ceremonies at the stone, and it is of course irresistible to graffitists...

Along the way I took the photograph above, of the Stone of Free Speech on Parliament Hill. Nobody seems to know the history of this stone bollard, but it has somehow acquired a reputation as a place where free speech is protected - which can only be a good thing in these censorious times. Modern 'pagans' seem to like holding ceremonies at the stone, and it is of course irresistible to graffitists...

Thursday 1 September 2016

Shakespeare's Butterflies: An Absence

Why are there no butterflies in Shakespeare? None, that is, beyond a few generic references to 'gilded butterflies', most notably Lear's 'so we'll live, And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh At gilded butterflies...' How was it that a poet so acutely aware of, and knowledgable about, the natural world, could discern butterflies - so beautiful, so various and so (then) abundant - only in generic terms?

Flowers, both wild and cultivated, are everywhere in Shakespeare, whose verse is the most beautifully flower-spangled in the language. There have been many studies of Shakespeare's flowers, and pictorial anthologies such as Walter Crane's Flowers from Shakespeare's Garden: A Posy from the Plays. More than fifty species are named in the works, along with forty-odd trees, and many 'Shakespeare gardens', on both sides of the Atlantic, have attempted to include them all in a suitably 'Shakespearean' setting. Birds too are abundant in Shakespeare - again some fifty-odd species, most of which Shakespeare clearly knew well - and indeed New York owes its starlings and house sparrows to a Shakespeare enthusiast's attempt to introduce 'Shakespeare's birds' to the New World.

'Shakespeare's butterflies', however, simply don't exist. And he was entirely representative of his times in not discriminating between species of butterfly: it was a surprisingly long time before anyone - even (proto-)scientists - did. During Shakespeare's lifetime, there seem to have been no recognised names for individual species. The first book to include any recognisable descriptions (of some eighteen species) was being worked on by the pioneering Thomas Moffet, but did not see the light of day until long after Shakespeare's death.

It was not until the great naturalist John Ray got to work that things advanced much further. In his Historia Insectorum (published in 1710), Ray described forty-eight species - but describe them was all he could do; there were no names for most of them. The description 'A large black butterfly with wings spotted with red and handsomely marked with white' (to translate from Ray's Latin) is clearly the Red Admiral, but no one, it seems, had yet called it that. Finally, in the early eighteenth century, James Petiver, 'the father of British butterflies', gave names to forty-nine species, including the Brimstone, the Painted Lady and a range of Hairstreaks, Admirals, Arguses and Tortoiseshells. Many of Petiver's names have subsequently been changed - his 'Hogs', for example, became 'Skippers', his 'Half-mourner' the 'Marbled White' - but finally Englishmen could talk about individual butterfly species, distinguish between them, and see them as something more than just 'gilded butterflies'.

To return to John Ray, he wrote one of the most eloquent summaries of the magical allure of butterflies:

'You ask what is the use of butterflies. I reply, to adorn the world and delight the eyes of men: to brighten the countryside, like so many jewels. To contemplate their exquisite beauty and variety is to experience the truest pleasure. To gaze inquiringly at such elegance of colour and form designed by the ingenuity of nature and painted by her artist's pencil is to acknowledge and adore the imprint of the art of God.'

Shakespeare, I'd like to believe, probably experienced a similar delight in looking at butterflies - but, for once, he simply did not have the words.

Flowers, both wild and cultivated, are everywhere in Shakespeare, whose verse is the most beautifully flower-spangled in the language. There have been many studies of Shakespeare's flowers, and pictorial anthologies such as Walter Crane's Flowers from Shakespeare's Garden: A Posy from the Plays. More than fifty species are named in the works, along with forty-odd trees, and many 'Shakespeare gardens', on both sides of the Atlantic, have attempted to include them all in a suitably 'Shakespearean' setting. Birds too are abundant in Shakespeare - again some fifty-odd species, most of which Shakespeare clearly knew well - and indeed New York owes its starlings and house sparrows to a Shakespeare enthusiast's attempt to introduce 'Shakespeare's birds' to the New World.

'Shakespeare's butterflies', however, simply don't exist. And he was entirely representative of his times in not discriminating between species of butterfly: it was a surprisingly long time before anyone - even (proto-)scientists - did. During Shakespeare's lifetime, there seem to have been no recognised names for individual species. The first book to include any recognisable descriptions (of some eighteen species) was being worked on by the pioneering Thomas Moffet, but did not see the light of day until long after Shakespeare's death.

It was not until the great naturalist John Ray got to work that things advanced much further. In his Historia Insectorum (published in 1710), Ray described forty-eight species - but describe them was all he could do; there were no names for most of them. The description 'A large black butterfly with wings spotted with red and handsomely marked with white' (to translate from Ray's Latin) is clearly the Red Admiral, but no one, it seems, had yet called it that. Finally, in the early eighteenth century, James Petiver, 'the father of British butterflies', gave names to forty-nine species, including the Brimstone, the Painted Lady and a range of Hairstreaks, Admirals, Arguses and Tortoiseshells. Many of Petiver's names have subsequently been changed - his 'Hogs', for example, became 'Skippers', his 'Half-mourner' the 'Marbled White' - but finally Englishmen could talk about individual butterfly species, distinguish between them, and see them as something more than just 'gilded butterflies'.

To return to John Ray, he wrote one of the most eloquent summaries of the magical allure of butterflies:

'You ask what is the use of butterflies. I reply, to adorn the world and delight the eyes of men: to brighten the countryside, like so many jewels. To contemplate their exquisite beauty and variety is to experience the truest pleasure. To gaze inquiringly at such elegance of colour and form designed by the ingenuity of nature and painted by her artist's pencil is to acknowledge and adore the imprint of the art of God.'

Shakespeare, I'd like to believe, probably experienced a similar delight in looking at butterflies - but, for once, he simply did not have the words.

Flower Alert

I've written about the flower painter Marianne North before, but here's something a little more substantial (and beautifully illustrated) that I wrote for the fabulous Freddie's Flowers website.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)