Wednesday, 30 September 2015

Off

I'm afraid I'm off gallivanting again - this time to the Cotentin Peninsula for a few days. I shall be on the Poole-Chergourg ferry at an unearthly hour tomorrow morning, heading for France for the first time this year. A bientot, mes amis...

Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Lessons of the Web

In this glorious Indian Summer weather, the spiders are making merry. I'm sure we haven't had such abundance and diversity in years. There are webs in every corner and vantage point in house and garden, and when I step out in the morning my face and hair will be instantly draped in filaments of gossamer - not a pleasant sensation in itself, but happy proof that the spiders thrive. What's especially gratifying is the range of types and species to be seen. It seemed a few years ago that the all-conquering incomer, the Daddy Long Legs Spider, with its lethal free-form web and voracious appetite, would wipe out all competition and establish an arachnid monoculture - but no, the threat passed and spider biodiversity returned. What Daddy Long Legs Spiders I see now are pale shadows of their former fearsome selves, and the big fat-bodied boys are back in charge.

The spider, tirelessly weaving its wondrous creations, has long been seen as an object lesson ('If at first you don't succeed, try, try again') and is irresistible to poets, good and bad. Among the good might be counted Walt Whitman, who saw in the spider's web an image of the soul - or rather (of course) his soul...

And Emily Dickinson, whose writings abound in spiders and spider imagery. In this poem she sees in the spider's web an image of her own hermetic art...

A Spider

sewed at Night

Without a Light

Upon an Arc of

White –

If Ruff it was

of Dame

Or Shroud of Gnome

Himself himself

inform –

Of Immortality

His Strategy

Was Physiognomy –

(That's in Dickinson's original layout and punctuation.) She also wrote that 'the spider as an artist has never been employed though his surpassing merit is freely certified by every broom and Bridget throughout a Christian land - neglected son of genius I take thee by the hand'.

And then there's Kay Ryan who, uniquely, sees the web from the spider's point of view, as an image of the sheer strenuousness of life...

The spider, tirelessly weaving its wondrous creations, has long been seen as an object lesson ('If at first you don't succeed, try, try again') and is irresistible to poets, good and bad. Among the good might be counted Walt Whitman, who saw in the spider's web an image of the soul - or rather (of course) his soul...

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark’d where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark’d how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch’d forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form’d, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

And Emily Dickinson, whose writings abound in spiders and spider imagery. In this poem she sees in the spider's web an image of her own hermetic art...

A Spider

sewed at Night

Without a Light

Upon an Arc of

White –

If Ruff it was

of Dame

Or Shroud of Gnome

Himself himself

inform –

Of Immortality

His Strategy

Was Physiognomy –

(That's in Dickinson's original layout and punctuation.) She also wrote that 'the spider as an artist has never been employed though his surpassing merit is freely certified by every broom and Bridget throughout a Christian land - neglected son of genius I take thee by the hand'.

And then there's Kay Ryan who, uniquely, sees the web from the spider's point of view, as an image of the sheer strenuousness of life...

SPIDERWEB

From other

angles the

fibers look

fragile, but

not from the

spider’s, always

hauling coarse

ropes, hitching

lines to the

best posts

possible. It’s

heavy work

everyplace,

fighting sag,

winching up

give. It

isn’t ever

delicate

to live.

From other

angles the

fibers look

fragile, but

not from the

spider’s, always

hauling coarse

ropes, hitching

lines to the

best posts

possible. It’s

heavy work

everyplace,

fighting sag,

winching up

give. It

isn’t ever

delicate

to live.

Monday, 28 September 2015

Mr Fortune's Maggot

Periodically, over the years, several people have urged me to read the novels of Sylvia Townsend Warner. Somehow I never got round to it - until now, when I have taken the plunge and read her Mr Fortune's Maggot (1927). (That's 'maggot' in the sense of 'a whimsical or perverse fancy; a crotchet'.)

I knew I was in for something special just from reading the author's Preface (to the Virago edition), which describes how the whole essence of Mr Fortune's Maggot came to her in a dream, which she wrote down as fast as she could; the first third of the novel is, she says, exactly as she dashed it off, with scarcely a word's alteration.

'I was really in a very advanced stage of hallucination when I finished the book - writing in manuscript and taking wads of it to be typed at the Westbourne Secretarial College in Queens Road.

I remember writing the last paragraph - and reading over the conclusion, and then impulsively writing the Envoy, and beginning to weep bitterly.

I took the two copies, one for England and one for USA, to Chatto and Windus myself. I was afraid to trust them by post. It was a very foggy day, and I was nearly run over. I left them with a sense that my world was now nicely and neatly over.'

So ends the Preface - and who could not read on after that? Especially after noting in the list of Thanks, 'I am greatly obliged to Mr Victor Butler for his assistance in the geometrical passages, and for the definition of an umbrella'.

Mr Fortune's Maggot is the story of the Rev. Timothy Fortune, a sweet-natured and well-meaning ex-bank clerk who becomes a missionary and ends up on the remote South Sea island of Fanua, where in three years he makes just one (apparent) convert, a delightful boy called Lueli. A kind of innocent but intense love swiftly develops between the missionary and his convert, who becomes his pupil as Mr Fortune sets about educating him in the knowledge and concerns of a wider world. This process gives rise to some of the funniest passages in the book:

'Since the teaching had to be entirely conversational, Lueli learned much that was various and seemingly irrelevant. Strange alleys branched off from the subject in hand, references and similes that strayed into the teacher's discourse as the most natural things in the world had to be explained and enlarged upon. In the middle of an account of Christ's entry into Jerusalem Mr Fortune would find himself obliged to break off and describe a donkey. This would lead naturally to the sands of Weston-super-Mare and a short account of bathing machines; and that afternoon he would take his pupil down to the beach and show him how English children turned sand out of buckets and built castles with a moat round them. Moats might lead to the feudal system and the Wars of the Barons. Fighting Lueli understood very well, but other aspects of civilisation needed a great deal of explaining; and Mr Fortune nearly gave himself heat apoplexy by demonstrating in the course of one morning the technique of urging a golf ball out of a bunker, and how English housewives crawl around on their hands and kneed scrubbing the linoleum.'

The education of Lueli is not exactly a howling success, especially when Mr Fortune is inspired to pass on the rudiments of plane geometry:

'Calm, methodical, with a mind prepared for the onset, he guided Lueli down to the beach and with a stick prodded a small hole in it.

"What is this?"

"A hole."

"No, Lueli, it may seem like a hole, but it is a point."

Perhaps he had prodded a little too emphatically. Lueli's mistake was quite natural. Anyhow, there were bound to be a few misunderstandings at the start.

He took out his pocket knife and whittled the end of the stick. Then he tried again.

"What is this?"

"A smaller hole."

"Point," said Mr Fortune suggestively.

"Yes, I mean a smaller point."

"No, not quite. It is a point, but it is not smaller. Holes may be of different sizes, but no point is larger or smaller than another point."

Lueli looked from the first point to the second. He seemed to be about to speak, but to think better of it. He removed his gaze to the sea.'

Mr Fortune's Maggot has been described as a satire on imperialism and Christian evangelism, but it is something far bigger and deeper than that, especially after the dramatic crisis of the story, triggered by an earthquake and volcanic eruption, in the course of which Mr Fortune loses not only his own God - which he finds surprisingly painless - but also, by his own imperious actions, Lueli's god (embodied in a wooden idol), which he finds infinitely more painful.

What this novel is, above all else, is a love story - a tender and entirely convincing account of the special love between Mr Fortune and Lueli, and how that love leads to a shattering emotional climax, from which Mr Fortune struggles to find a path to redemption. Happily, in the end, he does. And by then the author is as much in love with Mr Fortune as is Lueli. Indeed, she wrote of him: 'I love him with a dreadful uneasy passion which in itself denotes him a cripple...'

Sylvia Townsend Warner has a style all her own, and reading this book is an exhilarating, unsettling experience. You never quite know where you are with her, or she with her creation. The poet Gillian Beer writes that her novels 'at once baffle and possess the reader. Douce, whimsical and shifting seamlessy across verbal registers, they suddenly expose us to appalling suffering that cannot be set aside.' That seems a very good summing-up, as does John Updike's: 'Her stories tend to convince us in process and baffle us in conclusion; they are not rounded with meaning but lift jaggedly toward new and unseen developments.'

I should just add that Mr Fortune's Maggot also describes its island setting - and the terrible eruption that threatens to destroy it - with extraordinary vividness. Her only source for these passages was a single book - the letters of a woman missionary in Polynesia - borrowed from the Paddington Public Library.

I knew I was in for something special just from reading the author's Preface (to the Virago edition), which describes how the whole essence of Mr Fortune's Maggot came to her in a dream, which she wrote down as fast as she could; the first third of the novel is, she says, exactly as she dashed it off, with scarcely a word's alteration.

'I was really in a very advanced stage of hallucination when I finished the book - writing in manuscript and taking wads of it to be typed at the Westbourne Secretarial College in Queens Road.

I remember writing the last paragraph - and reading over the conclusion, and then impulsively writing the Envoy, and beginning to weep bitterly.

I took the two copies, one for England and one for USA, to Chatto and Windus myself. I was afraid to trust them by post. It was a very foggy day, and I was nearly run over. I left them with a sense that my world was now nicely and neatly over.'

So ends the Preface - and who could not read on after that? Especially after noting in the list of Thanks, 'I am greatly obliged to Mr Victor Butler for his assistance in the geometrical passages, and for the definition of an umbrella'.

Mr Fortune's Maggot is the story of the Rev. Timothy Fortune, a sweet-natured and well-meaning ex-bank clerk who becomes a missionary and ends up on the remote South Sea island of Fanua, where in three years he makes just one (apparent) convert, a delightful boy called Lueli. A kind of innocent but intense love swiftly develops between the missionary and his convert, who becomes his pupil as Mr Fortune sets about educating him in the knowledge and concerns of a wider world. This process gives rise to some of the funniest passages in the book:

'Since the teaching had to be entirely conversational, Lueli learned much that was various and seemingly irrelevant. Strange alleys branched off from the subject in hand, references and similes that strayed into the teacher's discourse as the most natural things in the world had to be explained and enlarged upon. In the middle of an account of Christ's entry into Jerusalem Mr Fortune would find himself obliged to break off and describe a donkey. This would lead naturally to the sands of Weston-super-Mare and a short account of bathing machines; and that afternoon he would take his pupil down to the beach and show him how English children turned sand out of buckets and built castles with a moat round them. Moats might lead to the feudal system and the Wars of the Barons. Fighting Lueli understood very well, but other aspects of civilisation needed a great deal of explaining; and Mr Fortune nearly gave himself heat apoplexy by demonstrating in the course of one morning the technique of urging a golf ball out of a bunker, and how English housewives crawl around on their hands and kneed scrubbing the linoleum.'

The education of Lueli is not exactly a howling success, especially when Mr Fortune is inspired to pass on the rudiments of plane geometry:

'Calm, methodical, with a mind prepared for the onset, he guided Lueli down to the beach and with a stick prodded a small hole in it.

"What is this?"

"A hole."

"No, Lueli, it may seem like a hole, but it is a point."

Perhaps he had prodded a little too emphatically. Lueli's mistake was quite natural. Anyhow, there were bound to be a few misunderstandings at the start.

He took out his pocket knife and whittled the end of the stick. Then he tried again.

"What is this?"

"A smaller hole."

"Point," said Mr Fortune suggestively.

"Yes, I mean a smaller point."

"No, not quite. It is a point, but it is not smaller. Holes may be of different sizes, but no point is larger or smaller than another point."

Lueli looked from the first point to the second. He seemed to be about to speak, but to think better of it. He removed his gaze to the sea.'

Mr Fortune's Maggot has been described as a satire on imperialism and Christian evangelism, but it is something far bigger and deeper than that, especially after the dramatic crisis of the story, triggered by an earthquake and volcanic eruption, in the course of which Mr Fortune loses not only his own God - which he finds surprisingly painless - but also, by his own imperious actions, Lueli's god (embodied in a wooden idol), which he finds infinitely more painful.

What this novel is, above all else, is a love story - a tender and entirely convincing account of the special love between Mr Fortune and Lueli, and how that love leads to a shattering emotional climax, from which Mr Fortune struggles to find a path to redemption. Happily, in the end, he does. And by then the author is as much in love with Mr Fortune as is Lueli. Indeed, she wrote of him: 'I love him with a dreadful uneasy passion which in itself denotes him a cripple...'

Sylvia Townsend Warner has a style all her own, and reading this book is an exhilarating, unsettling experience. You never quite know where you are with her, or she with her creation. The poet Gillian Beer writes that her novels 'at once baffle and possess the reader. Douce, whimsical and shifting seamlessy across verbal registers, they suddenly expose us to appalling suffering that cannot be set aside.' That seems a very good summing-up, as does John Updike's: 'Her stories tend to convince us in process and baffle us in conclusion; they are not rounded with meaning but lift jaggedly toward new and unseen developments.'

I should just add that Mr Fortune's Maggot also describes its island setting - and the terrible eruption that threatens to destroy it - with extraordinary vividness. Her only source for these passages was a single book - the letters of a woman missionary in Polynesia - borrowed from the Paddington Public Library.

Saturday, 26 September 2015

Glass and More

So, following Mary's tip (see below under 'Launching'), I made my way to Norbury - no, not the South London suburb - and duly found the church of St Mary and St Barlok (an Irish saint), in its picture-perfect setting, tucked away in rolling wooded countryside and forming a wonderfully picturesque ensemble with the manor house (1670s) and outbuildings. It is a quite extraordinary church, and most untypical of Derbyshire. The mighty chancel, flooded with light, is the kind of 'lantern in stone' you'd expect to come across in the flatlands of East Anglia. It seems to dwarf the nave (they are of more or less equal length), and was actually built first. Those tall wide windows, which look so Perpendicular, date to around 1300, when they must have looked quite startlingly 'modern' and daring in their pared-down structure and great expanse of glass.

And there's more than glass to see here. Standing in the chancel are two extraordinarily fine alabaster monuments (the best in England, according to the notice in the church) to members of the Fitzherbert family, the lords of the manor. Once one of the great English dynasties, the Fitzherberts paid a heavy price for their adherence to the Old Faith. The chap in my photograph above was a serious photographer who was painstakingly working his way around the monuments taking close-ups of the superb carving. As I took my picture with my cost-nothing mobile phone, I cheerily suggested he get rid of his tripod and fancy camera and try one of these. He took it in good part.

Among the other pleasures of this Derbyshire trip were a walk in Lathkill Dale - perhaps the most beautiful of them all - a drink in the pub that is home to the hen racing world championships (The Barley Mow, Bonsall), and one of the finest pizzas I've ever had, served in a decidedly eccentric one-woman pizzeria - more like a front parlour - in Wirksworth (Gino's - bring your own wine, and be sure to check it's actually open). The weather yesterday was sunny, and butterflies - far more numerous than down South now - were flying in abundance: Speckled Woods galore, Red Admirals and Peacocks, and a profusion of Tortoiseshells; the one below was inside Norbury Church, settled on that great East window.

And there's more than glass to see here. Standing in the chancel are two extraordinarily fine alabaster monuments (the best in England, according to the notice in the church) to members of the Fitzherbert family, the lords of the manor. Once one of the great English dynasties, the Fitzherberts paid a heavy price for their adherence to the Old Faith. The chap in my photograph above was a serious photographer who was painstakingly working his way around the monuments taking close-ups of the superb carving. As I took my picture with my cost-nothing mobile phone, I cheerily suggested he get rid of his tripod and fancy camera and try one of these. He took it in good part.

Among the other pleasures of this Derbyshire trip were a walk in Lathkill Dale - perhaps the most beautiful of them all - a drink in the pub that is home to the hen racing world championships (The Barley Mow, Bonsall), and one of the finest pizzas I've ever had, served in a decidedly eccentric one-woman pizzeria - more like a front parlour - in Wirksworth (Gino's - bring your own wine, and be sure to check it's actually open). The weather yesterday was sunny, and butterflies - far more numerous than down South now - were flying in abundance: Speckled Woods galore, Red Admirals and Peacocks, and a profusion of Tortoiseshells; the one below was inside Norbury Church, settled on that great East window.

Tuesday, 22 September 2015

Launching

For the next few days I'm going to be in Derbyshire, where my cousin is launching her new novel, The Green Table - details here - into the world. I haven't yet read it myself, but have heard good reports... Meanwhile, here's something of mine from another corner of the blogscape, about a writer I've mentioned from time to time on Nigeness.

Monday, 21 September 2015

The Music of Time Passing

The other evening, as I reached for a favourite CD of Dvorak string quartets (12 and 13, played by the Lindsays), it occurred to me that, as I grow older, I am more and more drawn to chamber music, songs, choral works and smaller-scale orchestral pieces - and less and less to the full-blown symphonies and big concertos that were the core of my listening decades ago when I first began to take an interest. Nowadays, many of those mighty works - especially those of the Romantic composers - seem uninviting, overblown, even bombastic and intimidating. This is unfair of course, as a judgment, but it expresses the way I often feel now, as I drift away from the grand and monumental to forms of music more intimate, perhaps 'lighter' in weight, subtler in effect, more impressionistic and allusive than overtly expressive. This has happened within the oeuvre of individual composers - notably Beethoven, whose symphonies I've more or less abandoned in favour of the late quartets - and likewise there are composers whose works I could only ever stomach on a small scale, most notably Mahler, and others I would in earlier years have written off as frivolous but now love, e.g. Poulenc.

I don't think I am alone in experiencing this movement in my musical taste as I grow older, and I suspect it might apply beyond the field of music. My reading seems to be heading in broadly the same direction, and I'll probably never get round to tackling those big blockbuster classics that I didn't read in earlier years. I marvel at the sheer stamina I had as a youthful reader, and know I could never emulate it now. As I also tend to read more slowly, I am less drawn to books that I know will take up weeks, even months, of my reading time - weeks that could be filled with a variety of lesser (in scale) delights.

I think the big stuff is best read when relatively young, when it will make more of an impact (on a necessarily less furnished mind) and when it will be more completely absorbed, will sink down and settle, forming a rich and fertile subsoil. Even if much of it is, to the conscious mind, forgotten (as it is in my case), something of that bulk reading will, I believe, continue to diffuse into all our later reading, colouring it, however faintly, and deepening and enriching our responses to what we read. With the spadework done, we can range at large, discovering that, with the fading of our youthful mental acuity, our vision becomes broader, less clearly defined, but deeper in insight and appreciation. Or so I like to believe.

Some similar movement seems to happen in the careers of some great artists, as they leave behind the unageing monuments of their prime and set sail into chartless waters - Titian's extraordinary late paintings, or Turner's, Beckett's Ill Seen Ill Said, Nabokov's Transparent Things, final condensates of their creators' genius. Or indeed Beethoven's late quartets. None of these would have been possible without what came before; they are the fruits of time and ageing - and, as we age ourselves, we respond to them more and more. Those ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds...

Talking of which, here is a beautiful piece I came across on YouTube the other day, by the Latvian composer Peteris Vasks - that's him taking a reluctant bow at the end of the performance. Enjoy, marvel.

I don't think I am alone in experiencing this movement in my musical taste as I grow older, and I suspect it might apply beyond the field of music. My reading seems to be heading in broadly the same direction, and I'll probably never get round to tackling those big blockbuster classics that I didn't read in earlier years. I marvel at the sheer stamina I had as a youthful reader, and know I could never emulate it now. As I also tend to read more slowly, I am less drawn to books that I know will take up weeks, even months, of my reading time - weeks that could be filled with a variety of lesser (in scale) delights.

I think the big stuff is best read when relatively young, when it will make more of an impact (on a necessarily less furnished mind) and when it will be more completely absorbed, will sink down and settle, forming a rich and fertile subsoil. Even if much of it is, to the conscious mind, forgotten (as it is in my case), something of that bulk reading will, I believe, continue to diffuse into all our later reading, colouring it, however faintly, and deepening and enriching our responses to what we read. With the spadework done, we can range at large, discovering that, with the fading of our youthful mental acuity, our vision becomes broader, less clearly defined, but deeper in insight and appreciation. Or so I like to believe.

Some similar movement seems to happen in the careers of some great artists, as they leave behind the unageing monuments of their prime and set sail into chartless waters - Titian's extraordinary late paintings, or Turner's, Beckett's Ill Seen Ill Said, Nabokov's Transparent Things, final condensates of their creators' genius. Or indeed Beethoven's late quartets. None of these would have been possible without what came before; they are the fruits of time and ageing - and, as we age ourselves, we respond to them more and more. Those ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds...

Talking of which, here is a beautiful piece I came across on YouTube the other day, by the Latvian composer Peteris Vasks - that's him taking a reluctant bow at the end of the performance. Enjoy, marvel.

Saturday, 19 September 2015

A Great-Uncle Writes...

I'm wondering if anyone out there has any suggestions for books to give to a bright and bookish about-to-be 16-year-old girl (my great-niece). Last year she read and enjoyed Gwen Raverat's Period Piece and E. Nesbit's Long Ago When I Was Young - so this is a girl whose reading extends, happily, way beyond recent fiction.

I'm wondering about My Antonia, So Long See You Tomorrow, The Member of the Wedding, True Grit? Funny they're all American...

Any ideas?

I'm wondering about My Antonia, So Long See You Tomorrow, The Member of the Wedding, True Grit? Funny they're all American...

Any ideas?

Thursday, 17 September 2015

John Creasey: Phenomenally Productive

Today, let us pause and doff our opera hats to the astoundingly prolific novelist John Creasey, born on this day in 1908. Even by the standards of the pulp writers of the last century (and he was several notches above mere pulp), Creasey was phenomenally productive and fast-working. In one year alone (1937), he published 29 titles, and in the course of a career of 40-odd years he turned out well over 600 novels, published under his own name and some 28 pseudonyms. These included, for his westerns, Ken Ranger and Tex Riley, and for his romances Margaret Cooke and Elise Fecamps. But it is for his thrillers are detective novels that he is best known; many were filmed or adapted for TV, and a surprisingly large number of them remain in print, more than 40 years after his death.

Creasey's most famous and successful creations were Commander George Gideon (of the Yard), Chief Inspector Roger West, Dr Palfrey, The Baron (John Mannering) and the monocled aristocrat (The Hon. Richard Rollison) known as The Toff. These series alone account for more than 200 titles, but were still in total the smaller part of Creasey's prodigious output. Somehow, in the midst of all this literary activity, Creasey also found time for a political career, first as a committed Liberal activist, later as founder of the All Party Alliance. And he was awarded an MBE for his services to the National Savings movement during the War.

They don't make them like John Creasey any more - and even if they did, the publishing industry and the reading public could no longer sustain such levels of output. Creasey was writing at a time when there was enormous demand for novels that offered the kind of easily-absorbed escapist entertainment that is now largely provided by television and, increasingly, online media.

Years ago, in the days when I used to enter the literary competitions in the Spectator and New Statesman, the challenge one week was to come up with titles of serious academic treatises on wildly unlikely writers. One of my entries was The Monocular Vision: Problems of Perception in the Toff Novels of John Creasey. I was rather pleased with that one...

Creasey's most famous and successful creations were Commander George Gideon (of the Yard), Chief Inspector Roger West, Dr Palfrey, The Baron (John Mannering) and the monocled aristocrat (The Hon. Richard Rollison) known as The Toff. These series alone account for more than 200 titles, but were still in total the smaller part of Creasey's prodigious output. Somehow, in the midst of all this literary activity, Creasey also found time for a political career, first as a committed Liberal activist, later as founder of the All Party Alliance. And he was awarded an MBE for his services to the National Savings movement during the War.

They don't make them like John Creasey any more - and even if they did, the publishing industry and the reading public could no longer sustain such levels of output. Creasey was writing at a time when there was enormous demand for novels that offered the kind of easily-absorbed escapist entertainment that is now largely provided by television and, increasingly, online media.

Years ago, in the days when I used to enter the literary competitions in the Spectator and New Statesman, the challenge one week was to come up with titles of serious academic treatises on wildly unlikely writers. One of my entries was The Monocular Vision: Problems of Perception in the Toff Novels of John Creasey. I was rather pleased with that one...

Wednesday, 16 September 2015

Funny Old World

Here are two current stories:

1: From Guantanamo - 'detained but ready to mingle'...

2: From the People's Republic of Corbynia, where all things are possible - 'this girl has a thing about beards'...

Which of these stories is a spoof? Or is it both? Or perhaps neither?

1: From Guantanamo - 'detained but ready to mingle'...

2: From the People's Republic of Corbynia, where all things are possible - 'this girl has a thing about beards'...

Which of these stories is a spoof? Or is it both? Or perhaps neither?

Tuesday, 15 September 2015

What's Killing Us Now

What would the founders of 'our' National Health Service make of this story - junk diet now killing more of us than cigs? I guess their jaws would drop and they would shake their heads in disbelief, wondering where it all went wrong. The nation was supposed to go on getting healthier and healthier once the State took over, with health education, rising living standards and advances in medicine and hygiene breeding a fitter population, and medical care provided free at the point of use to all who needed it. Indeed, the NHS was seriously expected to shrink and eventually all but disappear - not for nothing was it called a National Health Service.

What was wrong with this thinking? Simply that it was based on the classic false assumption that underlies most social sciences (especially economics): that people will act rationally and in pursuit of their own best interests. In fact, for much of the time, most people do no such thing; human nature is far more complex and contradictory than that. As Kant put it, 'Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.' The NHS was a classic 'straight thing' project, doomed to fail. But the kind of thinking that gave birth to it is still everywhere apparent, not least in the field of public health - as evidenced by the quotation that closes the Telegraph piece: More government intervention, taxes, duties, subsidies - that will sort it out. No, it won't.

What was wrong with this thinking? Simply that it was based on the classic false assumption that underlies most social sciences (especially economics): that people will act rationally and in pursuit of their own best interests. In fact, for much of the time, most people do no such thing; human nature is far more complex and contradictory than that. As Kant put it, 'Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.' The NHS was a classic 'straight thing' project, doomed to fail. But the kind of thinking that gave birth to it is still everywhere apparent, not least in the field of public health - as evidenced by the quotation that closes the Telegraph piece: More government intervention, taxes, duties, subsidies - that will sort it out. No, it won't.

Saturday, 12 September 2015

'The Canaletto of Dieppe'

At Dieppe

That's Arthur Symons's melancholy poetic response to Sickert's painting L'Hotel Royal, Dieppe - a wonderful picture that's the poster girl for the Sickert in Dieppe exhibition at Chichester's Pallant House gallery. Having foolishly missed Ravilious at Dulwich (I was sure it was on until the end of September - it wasn't), I at least made it to Chichester yesterday to see the Sickert. And well worth the journey it was.

It's a fine, painstakingly curated exhibition tracing Sickert's relationship with Dieppe over the years, focusing in particular on the period when he lived there and became, in his friend Jacques-Emile Blanche's phrase, 'the Canaletto of Dieppe'. Three rooms of well captioned paintings, etchings, sketches and photographs tell the story of Sickert's almost obsessive recording of the streets and churches, beach and harbour of Dieppe - from early studies clearly influenced by Whistler to later, freer and more 'impressionistic' works, bringing in bolder colour and freer brushwork. One room (of three) is devoted to paintings and studies of Dieppe's great Gothic church, St Jacques, which he painted from every angle and in every light (and a couple of pictures of St Remy).

Many of these pictures have not been seen in public for years, or at all, and they have never been brought together for an exhibition on this scale. Among the standouts (for me anyway) were The Red Shop (October Sun) with its glorious splash of vermilion; the dramatic - and large - Le Grand Duquesne with its looming statue dark against the light; Le Cafe Suisse, painted at the outset of the Great War; and Une Dieppoise, a striking image of a woman drawing water by the harbourside at dawn. But there are many more terrific pictures in this exhibition, and anyone with an interest in Sickert, or Dieppe - or, ideally, both - should head for Pallant House before October 4th.

And while you're there, look in on the one-room exhibition of pictures by Kenneth Rowntree, one of the Great Bardfield circle of artists (which most famously included Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious). This is his Tractor in Landscape, which was one of the most popular of the School Prints.

The grey-green stretch of sandy grass,

Indefinitely desolate;

A sea of lead, a sky of slate;

Already autumn in the air, alas!

One stark monotony of stone,

The long hotel, acutely white,

Against the after-sunset light

Withers grey-green, and takes the grass's tone.

Listless and endless it outlies,

And means, to you and me, no more

Than any pebble on the shore,

Or this indifferent moment as it dies.

Indefinitely desolate;

A sea of lead, a sky of slate;

Already autumn in the air, alas!

One stark monotony of stone,

The long hotel, acutely white,

Against the after-sunset light

Withers grey-green, and takes the grass's tone.

Listless and endless it outlies,

And means, to you and me, no more

Than any pebble on the shore,

Or this indifferent moment as it dies.

That's Arthur Symons's melancholy poetic response to Sickert's painting L'Hotel Royal, Dieppe - a wonderful picture that's the poster girl for the Sickert in Dieppe exhibition at Chichester's Pallant House gallery. Having foolishly missed Ravilious at Dulwich (I was sure it was on until the end of September - it wasn't), I at least made it to Chichester yesterday to see the Sickert. And well worth the journey it was.

It's a fine, painstakingly curated exhibition tracing Sickert's relationship with Dieppe over the years, focusing in particular on the period when he lived there and became, in his friend Jacques-Emile Blanche's phrase, 'the Canaletto of Dieppe'. Three rooms of well captioned paintings, etchings, sketches and photographs tell the story of Sickert's almost obsessive recording of the streets and churches, beach and harbour of Dieppe - from early studies clearly influenced by Whistler to later, freer and more 'impressionistic' works, bringing in bolder colour and freer brushwork. One room (of three) is devoted to paintings and studies of Dieppe's great Gothic church, St Jacques, which he painted from every angle and in every light (and a couple of pictures of St Remy).

Many of these pictures have not been seen in public for years, or at all, and they have never been brought together for an exhibition on this scale. Among the standouts (for me anyway) were The Red Shop (October Sun) with its glorious splash of vermilion; the dramatic - and large - Le Grand Duquesne with its looming statue dark against the light; Le Cafe Suisse, painted at the outset of the Great War; and Une Dieppoise, a striking image of a woman drawing water by the harbourside at dawn. But there are many more terrific pictures in this exhibition, and anyone with an interest in Sickert, or Dieppe - or, ideally, both - should head for Pallant House before October 4th.

And while you're there, look in on the one-room exhibition of pictures by Kenneth Rowntree, one of the Great Bardfield circle of artists (which most famously included Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious). This is his Tractor in Landscape, which was one of the most popular of the School Prints.

Friday, 11 September 2015

Questing

One of the pleasures of retirement is being able now and then to spend a sunny afternoon in a futile quest, and thoroughly enjoy it. Yesterday I went on such a quest, in the dubious hope of seeing, for the first time, the beautiful but notoriously elusive Brown Hairstreak butterfly. The males of this late-emerging species are almost never seen, and the females only when they descend to lay their eggs, delicately and singly, on blackthorn. I headed for a common where I knew Brown Hairstreaks were seen every year at around this time, and I made my way to that part of it where they were usually spotted, where the blackthorn grows in prickly abundance, at this time of year purple with ripening sloes.

It was gloriously sunny, but I knew I had probably left it too late - a few days earlier I might have stood a better chance, and a little earlier in the day; these Brown Hairstreaks like to lay their eggs around lunchtime. As it turned out (sorry to break the white-knuckle suspense), I was right; despite spending much time staring at blackthorn thickets, I saw no Hairstreaks. But what the hey, it was a delightful afternoon stroll, and various of my butterfly friends turned up along the way: Speckled Woods and Holly Blues, still very full of beans; tired Meadow Browns; a bright fresh Small Copper and a couple of Small Heaths (I only saw my first of this usually quite common species the other day, which is odd); a basking Comma and, back at the railway station, a fine Red Admiral feasting on a late-flowering Buddleia bush. There were also frequent flypasts by dragonflies of various sizes and colours - every summer the dragonflies seem to get more abundant. Also, along the way, a mighty thorn went straight through the sole of my left boot and into the ball of my foot. Little blood was drawn. This was Nature's way of telling me to get a new pair of boots...

So, for the second year running, I have drawn a blank on all the Hairstreaks - Green, White-Letter, Purple, the impossibly rare Black, and the elusive Brown. Which gives me an idea: maybe next year should be the Year of the Hairstreak, in which I finally track down all five? Talking of futile quests.

It was gloriously sunny, but I knew I had probably left it too late - a few days earlier I might have stood a better chance, and a little earlier in the day; these Brown Hairstreaks like to lay their eggs around lunchtime. As it turned out (sorry to break the white-knuckle suspense), I was right; despite spending much time staring at blackthorn thickets, I saw no Hairstreaks. But what the hey, it was a delightful afternoon stroll, and various of my butterfly friends turned up along the way: Speckled Woods and Holly Blues, still very full of beans; tired Meadow Browns; a bright fresh Small Copper and a couple of Small Heaths (I only saw my first of this usually quite common species the other day, which is odd); a basking Comma and, back at the railway station, a fine Red Admiral feasting on a late-flowering Buddleia bush. There were also frequent flypasts by dragonflies of various sizes and colours - every summer the dragonflies seem to get more abundant. Also, along the way, a mighty thorn went straight through the sole of my left boot and into the ball of my foot. Little blood was drawn. This was Nature's way of telling me to get a new pair of boots...

So, for the second year running, I have drawn a blank on all the Hairstreaks - Green, White-Letter, Purple, the impossibly rare Black, and the elusive Brown. Which gives me an idea: maybe next year should be the Year of the Hairstreak, in which I finally track down all five? Talking of futile quests.

Thursday, 10 September 2015

Semper Eadem

Two women have been with me all through my conscious life - the Queen and Peggy Archer*. There was a third, my mother, up until a couple of years ago, and these three female figures were oddly intertwined at some level of my consciousness. I know I would feel it strongly, perhaps disproportionately so, if one of the remaining two were to die. If? I suppose it's more a matter of when now, but I devoutly hope that the Queen, in particular, lives long, preferably into triple figures, preferably long enough to avoid the embarrassment of a Caroline succession.

The Queen - who yesterday, as all the world knows, became the longest-serving British monarch ever - is the living embodiment of the great English public virtues of reticence, restraint, modesty and discretion, and in all her long reign she has scarcely put a foot wrong. The fact that, after all these years, we essentially know nothing of her private views on anything is at once extraordinary, refreshing and laudable, and makes her virtually unique among public figures. That she has survived so long and is still so obviously popular owes much to that remarkable restraint, a product of her equally old-fashioned devotion to duty - but also to the Queen's having absorbed the great lesson enunciated in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's The Leopard: If you want everything to stay the same, everything must change. The stability and apparent changelessness of our monarchy is the product of continual quiet adaptation to changing times - and Elizabeth's have certainly been changing times. One of history's other great exemplars of continuity through change was the first Elizabeth, whose motto was Semper Eadem. Always the same. Which sparks memories of my father's bathroom recitations of stirring patriotic verse - here's strong stuff from Macaulay's The Armada:

*Note for American readers (and others): Peggy Archer is the matriarch of the Archer family of Ambridge, whose lives are chronicled in a long-running, strangely addictive 'everyday story of country folk', The Archers, on BBC Radio 4. Peggy has been played by the same actress since 1950.

The Queen - who yesterday, as all the world knows, became the longest-serving British monarch ever - is the living embodiment of the great English public virtues of reticence, restraint, modesty and discretion, and in all her long reign she has scarcely put a foot wrong. The fact that, after all these years, we essentially know nothing of her private views on anything is at once extraordinary, refreshing and laudable, and makes her virtually unique among public figures. That she has survived so long and is still so obviously popular owes much to that remarkable restraint, a product of her equally old-fashioned devotion to duty - but also to the Queen's having absorbed the great lesson enunciated in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's The Leopard: If you want everything to stay the same, everything must change. The stability and apparent changelessness of our monarchy is the product of continual quiet adaptation to changing times - and Elizabeth's have certainly been changing times. One of history's other great exemplars of continuity through change was the first Elizabeth, whose motto was Semper Eadem. Always the same. Which sparks memories of my father's bathroom recitations of stirring patriotic verse - here's strong stuff from Macaulay's The Armada:

*Note for American readers (and others): Peggy Archer is the matriarch of the Archer family of Ambridge, whose lives are chronicled in a long-running, strangely addictive 'everyday story of country folk', The Archers, on BBC Radio 4. Peggy has been played by the same actress since 1950.

Wednesday, 9 September 2015

Gas Guzzlers

Today on the reborn Dabbler (good to have Brit's Monday Diary back), there's a piece by me on the pleasures of laughing gas.

Tuesday, 8 September 2015

Fitzgerald, Mew

Penelope Fitzgerald's Charlotte Mew and Her Friends, which I have just read, is a model of what a biography should be (and these days so seldom is) - short, sharp, empathetic and imaginatively engaged, an acute study in character rather than an accumulation of facts in a dreary chronological plod. Michael Holroyd describes Fitzgerald's book as 'a beautifully choreographed performance between two writers', and so it is.

I knew little of Charlotte Mew or her poetry, but now have a very clear picture of her self-thwarting nature, in all its oddity, contradiction and curious charm. And not only of her but (as the title suggests) the people around her, deftly portrayed by Fitzgerald, sometimes in a few words. Charlotte's mother, for example, was 'a tiny, pretty, silly young woman who grew, in time, to be a very silly old one. But she had the great strength of silliness, smallness and prettiness in combination, in that it never occurred to her that she would not be protected and looked after, and she always was.'

With her keen, but always forgiving, eye for the ridiculous, Fitzgerald paints vivid portraits of two men who were very important to Charlotte's fitful literary career: Harold Monro of the Poetry Bookshop - alcoholic, unhappily gay, but willing to do anything for 'his' writers - and Sydney Cockerell of the Fitzwilliam Museum, fixer and networker supreme, a terrible fusspot, but (with his wife Kate) a much-needed tower of strength to Charlotte. Lesser figures cross the stage, such as Walter de la Mare, who 'had a more exact ear than perhaps any other English poet. In his verse every pause, as well as every stress, falls into place like a language we once knew, but have to be reminded of' (a perfect summing-up) - and who, Fitzgerald also tells us, 'once argued for two days over whether marmalade could properly be called a kind of jam'.

Fitzgerald tells us all we need to know about the Georgian poet John Drinkwater by listing the contents of his Poems of Love and Earth, in which he 'thanks God for (1) sleep, (2) clear day through little leaded panes, (3) shining well water, (4) warm golden light, (5) rain and wind, apparently at the same time as (2), (6) swallows', etc, etc. Charlotte Mew and Her Friends is as much a portrait of a literary milieu as of a life, achieved in remarkably few pages thanks to Fitzgerald's elegantly concise style, delicate touch and sharp eye for the telling detail. It is also - despite the sadness of its principal subject's short, troubled life - great fun to read, with something new and surprising at every turn. Even the index is enjoyable. Here is the entry for Wek, the Mew family's long-lived parrot:

'awkward character, 94, 97; Alida Monro introduced to him, 148; has queer turns, 150; chews up CM's MSS, 149; poorly, 177; dislikes men, 177; CM and Anne distressed at his death, 177-8.'

(The death of Wek, by the way, is a hilarious scene of black comedy.)

I finished this book determined to read more of Charlotte Mew's extraordinary poetry - and Penelope Fitzgerald's biography of Edward Burne-Jones, her first published work.

I knew little of Charlotte Mew or her poetry, but now have a very clear picture of her self-thwarting nature, in all its oddity, contradiction and curious charm. And not only of her but (as the title suggests) the people around her, deftly portrayed by Fitzgerald, sometimes in a few words. Charlotte's mother, for example, was 'a tiny, pretty, silly young woman who grew, in time, to be a very silly old one. But she had the great strength of silliness, smallness and prettiness in combination, in that it never occurred to her that she would not be protected and looked after, and she always was.'

With her keen, but always forgiving, eye for the ridiculous, Fitzgerald paints vivid portraits of two men who were very important to Charlotte's fitful literary career: Harold Monro of the Poetry Bookshop - alcoholic, unhappily gay, but willing to do anything for 'his' writers - and Sydney Cockerell of the Fitzwilliam Museum, fixer and networker supreme, a terrible fusspot, but (with his wife Kate) a much-needed tower of strength to Charlotte. Lesser figures cross the stage, such as Walter de la Mare, who 'had a more exact ear than perhaps any other English poet. In his verse every pause, as well as every stress, falls into place like a language we once knew, but have to be reminded of' (a perfect summing-up) - and who, Fitzgerald also tells us, 'once argued for two days over whether marmalade could properly be called a kind of jam'.

Fitzgerald tells us all we need to know about the Georgian poet John Drinkwater by listing the contents of his Poems of Love and Earth, in which he 'thanks God for (1) sleep, (2) clear day through little leaded panes, (3) shining well water, (4) warm golden light, (5) rain and wind, apparently at the same time as (2), (6) swallows', etc, etc. Charlotte Mew and Her Friends is as much a portrait of a literary milieu as of a life, achieved in remarkably few pages thanks to Fitzgerald's elegantly concise style, delicate touch and sharp eye for the telling detail. It is also - despite the sadness of its principal subject's short, troubled life - great fun to read, with something new and surprising at every turn. Even the index is enjoyable. Here is the entry for Wek, the Mew family's long-lived parrot:

'awkward character, 94, 97; Alida Monro introduced to him, 148; has queer turns, 150; chews up CM's MSS, 149; poorly, 177; dislikes men, 177; CM and Anne distressed at his death, 177-8.'

(The death of Wek, by the way, is a hilarious scene of black comedy.)

I finished this book determined to read more of Charlotte Mew's extraordinary poetry - and Penelope Fitzgerald's biography of Edward Burne-Jones, her first published work.

Sunday, 6 September 2015

Kavanagh, Gurney

The other day I learnt that one of my favourite journalists - essayists would be a much better word - P.J. Kavanagh, had died. He was also a poet, novelist, broadcaster, memoirist, lecturer and actor (he played, believe it or not, Fr Seamus Fitzpatrick, collector of Nazi memorabilia, in a classic episode of Father Ted). But I knew him best from his writings in various newspapers and magazines (notably The Spectator and TLS), pieces about books and writers and, preeminently, people and places - which is the title of a collection of his essays that I recently spotted in a local charity shop. Naturally I pounced on it, but then saw that is was priced at an exorbitant £20, because it was signed. Undeterred, I took to the internet and had soon tracked down a copy of People and Places for a couple of pounds. When it arrived, I was delighted to find that it too was signed...

The superb essay that opens the volume - Naming Names - is a good example of Kavanagh at his best. Its subject is the power of names - a subject Kavanagh explores in relation to the poet and composer Ivor Gurney, whose Collected Poems (1982) he edited. Kavanagh takes a journey - 'an exercise in humility and continuity' - in the Somme region where Gurney served in the Great War, an experience that the poet returned to obsessively in his troubled later years. He finds the mausoleum at Caulaincourt into which Gurney and his fellow soldiers crawled for shelter - finds it by asking a workman at the roadside who knew instantly what Kavanagh was looking for and grinned widely: 'The Boche never found them out.' He visits Laventie, 'The town itself with plane trees, and small-spa air' - Gurney's spot-on description (we've all been to, or through, such towns in northern France).

Kavanagh is moved to come across some of the countless tiny war cemeteries, like English gardens, tucked away in corners of cornfields, orchards and copses all over the countryside, still carefully tended. He quotes in full a Gurney poem about a hasty wayside burial, Butchers and Tombs, and tells how, finding the names of two of Gurney's fellow Gloucesters in a later poem, he telephoned the War Graves Commission and in 20 minutes had the locations of their graves.

All this and more is done in six elegantly written pages. Then there is a two-page postscript describing the unveiling of a plaque in Westminster Abbey to 16 'war poets', including Ivor Gurney. Rightly Kavanagh has reservations about the use of the term 'war poet' - not least because 'it held back the recognition of Edward Thomas for years, because he hardly deigned to mention the war, although he fought and was killed in it'. Delving in Gurney's manuscripts written in the asylum where he spent his later years, Kavanagh thought some were signed 'Ivor Gurney. Was Poet.' 'This sounded heart-breaking, as well as heart-broken. But when I grew used to his handwriting and saw that he had written not 'Was Poet' but 'War Poet', the pathos was even louder. He had heard of the new category and was crying out to be included: anything, to be heard.'

People and Places s going to be at my bedside for some while, I think. Meanwhile, here is one of Gurney's songs - the extraordinarily beautiful Sleep.

The superb essay that opens the volume - Naming Names - is a good example of Kavanagh at his best. Its subject is the power of names - a subject Kavanagh explores in relation to the poet and composer Ivor Gurney, whose Collected Poems (1982) he edited. Kavanagh takes a journey - 'an exercise in humility and continuity' - in the Somme region where Gurney served in the Great War, an experience that the poet returned to obsessively in his troubled later years. He finds the mausoleum at Caulaincourt into which Gurney and his fellow soldiers crawled for shelter - finds it by asking a workman at the roadside who knew instantly what Kavanagh was looking for and grinned widely: 'The Boche never found them out.' He visits Laventie, 'The town itself with plane trees, and small-spa air' - Gurney's spot-on description (we've all been to, or through, such towns in northern France).

Kavanagh is moved to come across some of the countless tiny war cemeteries, like English gardens, tucked away in corners of cornfields, orchards and copses all over the countryside, still carefully tended. He quotes in full a Gurney poem about a hasty wayside burial, Butchers and Tombs, and tells how, finding the names of two of Gurney's fellow Gloucesters in a later poem, he telephoned the War Graves Commission and in 20 minutes had the locations of their graves.

All this and more is done in six elegantly written pages. Then there is a two-page postscript describing the unveiling of a plaque in Westminster Abbey to 16 'war poets', including Ivor Gurney. Rightly Kavanagh has reservations about the use of the term 'war poet' - not least because 'it held back the recognition of Edward Thomas for years, because he hardly deigned to mention the war, although he fought and was killed in it'. Delving in Gurney's manuscripts written in the asylum where he spent his later years, Kavanagh thought some were signed 'Ivor Gurney. Was Poet.' 'This sounded heart-breaking, as well as heart-broken. But when I grew used to his handwriting and saw that he had written not 'Was Poet' but 'War Poet', the pathos was even louder. He had heard of the new category and was crying out to be included: anything, to be heard.'

People and Places s going to be at my bedside for some while, I think. Meanwhile, here is one of Gurney's songs - the extraordinarily beautiful Sleep.

Saturday, 5 September 2015

Hampstead Addenda

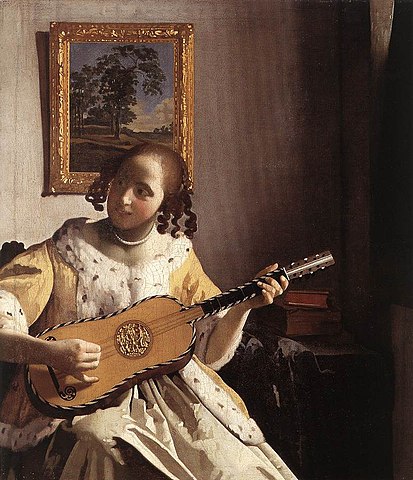

I forgot to mention Kenwood's other great art treasure - this Vermeer of a girl playing a guitar (then considered a rather racy and novel instrument in the Netherlands). It's a fascinating, mesmerising work, but also faintly unsettling, and I can't say it's among my favourite Vermeers. I prefer the subtler, more nuanced handling of tone, colour and texture in the great interiors of the artist's middle period. The Guitar Player is a later work, with the colours lying together in sharply defined planes, rather in the manner of some early Manets. This gives an oddly photographic effect, as if the painting is the product of one of Vermeer's experiments with optical devices. The off-kilter composition is odd and hard to explain, and the painting lacks the peculiar luminosity and the character of stillness and meditative inwardness that gives the greatest Vermeers their extraordinary, quasi-spiritual power. This girl, her face flushed with pleasure, looks emphatically outward, not inward, grinning with simple, immediate pleasure as she plays. (And a grin was a rare thing in art, before Vermeer's compatriot Frans Hals made it his stock in trade.)

Just weeks after Vermeer's death, his widow, struggling to survive, was obliged to use this painting and A Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid to settle a debt of 617 guilders with Delft's master baker.

In November 1818, John Keats wrote from Hampstead to his brother George: 'I must not forget to tell you that a few days since I went with Dilke a shooting on the heath and stot [shot] a Tomtit - There were as many guns abroad as Birds.'

On 16 August 1820 - six months before his death - Keats, in a letter to Shelley, wrote: 'I remember you advising me not to publish my first-blights, on Hampstead Heath - I am returning advice upon your hands. Most of the Poems in the volume I send you have been written above two years, and would never have been publish'd but from a hope of gain: so you see I am inclined enough to take your advice now...'

The volume Keats sent to Shelley was Lamia, Isabella & c. It was found, two years later, folded back in the drowned Shelley's pocket, and Leigh Hunt claimed that he tossed it onto the poet's funeral pyre (though, in point of sober fact, he seems to have stayed in the attendant carriage during the cremation).

Just weeks after Vermeer's death, his widow, struggling to survive, was obliged to use this painting and A Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid to settle a debt of 617 guilders with Delft's master baker.

In November 1818, John Keats wrote from Hampstead to his brother George: 'I must not forget to tell you that a few days since I went with Dilke a shooting on the heath and stot [shot] a Tomtit - There were as many guns abroad as Birds.'

On 16 August 1820 - six months before his death - Keats, in a letter to Shelley, wrote: 'I remember you advising me not to publish my first-blights, on Hampstead Heath - I am returning advice upon your hands. Most of the Poems in the volume I send you have been written above two years, and would never have been publish'd but from a hope of gain: so you see I am inclined enough to take your advice now...'

The volume Keats sent to Shelley was Lamia, Isabella & c. It was found, two years later, folded back in the drowned Shelley's pocket, and Leigh Hunt claimed that he tossed it onto the poet's funeral pyre (though, in point of sober fact, he seems to have stayed in the attendant carriage during the cremation).

Patrick Leigh Fermor: Firm Views on Moussaka

On the subject of Greek food, Patrick Leigh Fermor was clear about one thing: he could not stand moussaka. One day, however, his cook decided to put this prejudice to the test. She served him a moussaka, not telling him what it was, and awaited the outcome. The moussaka was made to the cook's own recipe - which involved frying all the vegetables (aubergine, courgette, potato) in olive oil and making a notably rich bechamel sauce - and she believed this to be the finest moussaka available to man. PLF ate the moussaka with relish, declared it delicious, and inquired what it was. 'Moussaka' announced the cook triumphantly. 'But I hate moussaka!' declared the great man.

I owe this insight into the home life of Patrick Leigh Fermor to Rick Stein, who in last night's episode of From Venice to Istanbul visited the writer's villa in the Mani and met the delightful woman who cooked for him.

I owe this insight into the home life of Patrick Leigh Fermor to Rick Stein, who in last night's episode of From Venice to Istanbul visited the writer's villa in the Mani and met the delightful woman who cooked for him.

Wednesday, 2 September 2015

A Hampstead Jaunt

Yesterday I took a walk in that 'suburban Nirvana' (as Wilkie Collins called it), Hampstead Heath - a Nirvana that seems much more heavily wooded and overgrown than when it was a haunt of my misspent late youth. Our aim was to visit Kenwood to see the paintings, and we did at length emerge from the suburban jungle to the prospect of its dazzling white facade above a sweep of green and a fine lake. Sitting on a bench on the verandah at the side of the house was a familiar figure - Julian flippin' Barnes. That's Hampstead for you. His legs were crossed and he was earnestly scrutinising a folded page torn from a newspaper - probably doing his Sudoku...

We left him unmolested, entered the house, and had just finished touring the upstairs rooms - portrait, portraits, more portraits - when suddenly the alarm started sounding, urgently and insistently, with an automated male voice ordering us repeatedly to leave the building by the nearest exit. This was all getting a tad surreal. Happily, after mustering outside the building, we were all allowed back within ten minutes or so, to be informed that it was only a drill. So we were able to linger long before Kenwood's astounding Rembrandt self-portrait. I'd forgotten that above this wonder hangs Sir Joshua Reynolds' lively self-portrait (in spectacles), and to its right a very fine Portrait of a Lady, thought to be another Rembrandt when it was bought but now known to be by Ferdinand Bol.

The dim panelled interiors of the Spaniards Inn seemed little changed since John Keats drank there - and, according to the proprietors of the Spaniards Inn, wrote his Ode to a Nightingale in the gardens. By way of contrast, Jack Straw's Castle, the huge ramshackle pub where I laid the foundations for some of the most blinding hangovers of my life, is now spruced up, bland and blank - and the entire building is an up-market fitness centre. O tempora, o mores...

We left him unmolested, entered the house, and had just finished touring the upstairs rooms - portrait, portraits, more portraits - when suddenly the alarm started sounding, urgently and insistently, with an automated male voice ordering us repeatedly to leave the building by the nearest exit. This was all getting a tad surreal. Happily, after mustering outside the building, we were all allowed back within ten minutes or so, to be informed that it was only a drill. So we were able to linger long before Kenwood's astounding Rembrandt self-portrait. I'd forgotten that above this wonder hangs Sir Joshua Reynolds' lively self-portrait (in spectacles), and to its right a very fine Portrait of a Lady, thought to be another Rembrandt when it was bought but now known to be by Ferdinand Bol.

The dim panelled interiors of the Spaniards Inn seemed little changed since John Keats drank there - and, according to the proprietors of the Spaniards Inn, wrote his Ode to a Nightingale in the gardens. By way of contrast, Jack Straw's Castle, the huge ramshackle pub where I laid the foundations for some of the most blinding hangovers of my life, is now spruced up, bland and blank - and the entire building is an up-market fitness centre. O tempora, o mores...

Tuesday, 1 September 2015

Dabbler Redivivus

The first day of a new month (and national Random Acts of Kindness Day in New Zealand) and - rejoice! - The Dabbler is back in action, with the latest of Jonathan Law's fascinating Phantom Libraries.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)