Yesterday to Shoreditch to visit the Geffrye Museum, as it used to be known; it's now the Museum of the Home. It's a whole lot more user-friendly, family-friendly, high-tech and multi-media than it was when I was last there, but then that was upward of 30 years ago. The suite of domestic interiors from various periods that form the core of the museum occupy fine early 18th-cetury almshouses endowed by Sir Robert Geffrye, a wealthy merchant and Lord Mayor of London. He was also, like anyone with any money at that time, an investor in the Atlantic slave trade, and even had a share in the ownership of a slave ship. He is therefore in the crosshairs of the new iconoclasts, and plans are afoot to remove the statue of Geffrye that stands over the entrance to the chapel and put it somewhere less conspicuous where it can be 'contextualised'. I don't know if there are also plans to 'do a Jesus' and remove the very grand memorial plaque that is an equally conspicuous feature of the chapel interior, but if so, they will no doubt have the full backing of Justin Welby. It occurred to me recently that anyone with any money now, even if it's only in a basic pension fund, will almost certainly be investing in fossil fuel production. Could it be that future generations will judge us as harshly for that as the 'woke' of today judge historical figures for any investment in slavery? On present trends, I wouldn't rule it out...

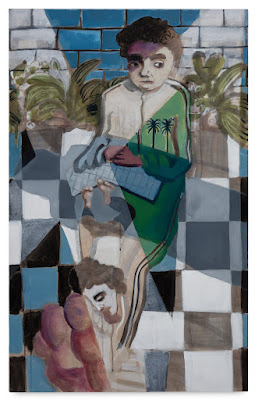

After the Geffrye, we (my cousin and I) walked along the canal towards St Pancras in dazzling low sunlight. Along the way, we dropped in on a canalside gallery, where there was an exhibition, titled Ghost Stories, of paintings by a young(ish) American-Dutch-Surinamese called Miko Veldkamp. I had never heard of him before, but liked much of what I saw. His paintings, quite large and freely painted, are a kind of palimpsest, with images from different times and places showing through the shimmering surface. In this they reminded me of the work of another young(ish) artist, Nick Goss, whose work I happened on at Pallant House a while ago, sharing space with the Harold Gilman exhibition, though Veldkamp's palette is generally much brighter. There is real beauty, or so it seems to me, in many of the paintings in Ghost Stories, and two or three I would happily have walked away with. It's good to know there are still artists who are painting seriously and well. That's one of Veldkamp's at the top, and you can read about him, and see more of his work, here, though his paintings don't reproduce well. You have to see them.