My latest charity bookshop find was a book I didn't even know existed – Nietzsche in Turin by Lesley Chamberlain. I was partly attracted by the cover design, and the fact that the book was published by the excellent Pushkin Press. As for Nietzsche, although I've long suspected that Jeeves was probably right about him – 'Fundamentally unsound, sir' – I've always found him a fascinating figure, and was keen to learn more. Chamberlain's book focuses on the year 1888, when Nietzsche, ever the wanderer, moved to Turin, a city he found exactly suited to his needs and tastes. Here he wrote three of his most important works – Twilight of the Idols (which I believe I might have read many years ago), The Antichrist and Ecce Homo – before descending into madness in the first days of 1889. A crucial year then, which Chamberlain chronicles in thoroughly readable manner, while filling in a lot of background information we need to know to understand Nietzsche's development. Along the way she demolishes various damaging misconceptions about Nietzsche, always emphasising the complexity and subtlety of his thought, which never ossified into dogma, a single 'Nietzschean' philosophy. As he said himself, 'There are no philosophies, only philosophers'.

I've already learnt a lot about this troubled, anxious, insecure man. I knew he was musical, and had been hugely impressed by Wagner, but I never realised quite how important music was to him, and how intense was the relationship with Wagner, his former idol whom he ceased to worship after he created the Ring Cycle, a work which Nietzsche found in many ways repellent (I know the feeling...). I'm finding Nietzsche in Turin surprisingly, genuinely enjoyable, and have already gained much from it, including some choice quotations from the ever quotable philosopher. Here's one with, I think, a lot of truth in it (truth that many Germanic and other philosophers would have done well to remember): 'What is good is light. Everything divine runs on delicate feet.' And here is a little sidelight on the Russian literary critic Belinsky, who 'told how for several years Schiller's moral idealism addicted him to graceful abstinence for the body and dignity for the soul. He also related how, when for compelling ideological reasons he gave up Schiller for Hegel, he went straight to a brothel.' How charming is divine philosophy!

Wednesday, 31 August 2022

A Nietzschean Find

Tuesday, 30 August 2022

'Great Reads...'

I must admit I had no idea there was such a thing as the Big Jubilee Read going on until I stepped into my local library today and noticed a display table devoted to it, promising 'Great reads by celebrated authors from the Commonwealth'. There were a dozen or so volumes displayed, including some that seemed worthy choices – Rohinton Mistry's A Fine Balance, V.S. Naipaul's A House for Mr Biswas, Derek Walcott's Omeros (represented only by a Study Guide, oddly) and... Henry James's What Maisie Knew, two copies of which, in different editions, were on display. Could Henry James conceivably be described as a 'celebrated author from the Commonwealth'? What was this Big Jubilee Read anyway? I checked it out, and found the full list of 70 titles, compiled from readers' suggestions and the thoughts of librarians, booksellers and 'literature specialists'. England and the home nations are represented in the list, with mostly rather worthy titles that carefully skirt anything like popular literature or even such obvious behemoths as Tolkien and J.K. Rowling. Jean Rhys (Wide Sargasso Sea) is fortunate in representing both Dominica and Wales, while Muriel Spark (The Girls of Slender Means) is there for Scotland. Nineteen of the 70 titles have won the Booker Prize – a telling fact... And Henry James? No, he is not on the list, which only goes back as far as the 1950s. So presumably it was a mistake – perhaps someone misread one of the titles on the list, Marlon James's The Book of Night Women? Who knows, but let's hope some reader picks up What Maisie Knew, enjoys it, and decides to read more James. Libraries are all about serendipity, or should be.

Chester beats Venice, Belfast beats Rome...

Fond though I am of Chester – a town I'll be visiting again the week after next, as it happens – I was startled to discover that it has been declared 'the most beautiful city in the world'. This is not a matter of opinion: it has been established by, ahem, 'science'. In fact it was established by applying one simple metric – the proportion of the city's buildings in which the Golden Ratio can be detected. The Golden Ratio, or the Divine Proportion, or the Golden Section, is an aesthetically pleasing proportion that is to be observed in nature as well as art, and can be expressed mathematically as 1:1.618033... etc. (an irrational number). The Golden Section makes a division such that the ratio between the smaller and the larger portion is the same as that between the larger and the whole. I remember once studying the façade of Palladio's great Venetian church Il Redentore (below) in terms of the Golden Section – the kind of exercise that can drive a fellow slightly mad, as once you see it, it seems to be everywhere. But in Chester? With its abundance of fake-Jacobethan street fronts, I would have thought it would score low on the Golden Ratio front. But no: according to the research project commissioned by, ahem again, Online Mortgage Advisor, the buildings of Chester have a higher incidence of the Golden Ratio (83.7pc) than Venice (83.3) or London (83) and Chester is therefore, er, 'more beautiful'. The complete Top Ten of most beautiful cities, by this criterion, are, from 1 to 10, Chester, Venice, London, Belfast, Rome, Barcelona, Liverpool, Durham, Bristol, Oxford – a truly bizarre ranking that might make the basis for a question in some esoteric quiz, maybe that incomprehensible TV show Only Connect.

Sunday, 28 August 2022

Betjeman's Edwardian Sunday

Busyness (mostly domestic) and the mental torpor of summer have prevented me doing much blogging lately, but I note that today is John Betjeman's birthday (born 1906), and that is always fun to mark. Not only Betj's birthday but also a Sunday – just the day to remember him. I'm passing my Sunday in a cathedral town – no prizes for guessing which – but in the poem below Betjeman imagines an Edwardian Sunday in a prosperous suburb of Sheffield. Many parts of that 'hill-shadowed city', with its distinctive topography, still have the look and feel evoked by Betjeman here (Broomhill itself is now, I believe, full of student accommodation). Re-entering the Edwardian world came easily to Betjeman, whose sensibility was formed in an Edwardian middle-class world, whatever evolutions it was to go through later, and whose memories of the period remained very much alive, as his autobiographical writings show.

In An Edwardian Sunday, the jogalong rhythm and insistent rhyming are thoroughly Edwardian, and the first couplet is weak, but things improve as it goes along, and it builds into an evocative, cleverly detailed picture of a past time and place and mood, complete with the touch of Eros that so often pops up in Betjeman's most innocent-seeming verse ('As Eve shows her apple through rich bombazine')... 'Ponticum' is a rhododendron species popular with the Victorians, and the 'Ebenezer' in the last section is Ebenezer Elliott, the 'Corn Law Rhymer', a Sheffield hero.

An Edwardian Sunday, Broomhill, Sheffield

Wednesday, 24 August 2022

'Do you like chocolates?'

Talking of Chekhov (as we almost were), I just came across this poem by Louis Simpson, which illustrates one of Chekhov's many endearing traits – his polite refusal to be drawn into 'serious' conversation...

Chocolates

Once some people were visiting Chekhov.

While they made remarks about his genius

the Master fidgeted. Finally

he said, "Do you like chocolates?"

They were astonished, and silent.

He repeated the question,

whereupon one lady plucked up her courage

and murmured shyly, "Yes."

"Tell me," he said, leaning forward,

light glinting from his spectacles,

"what kind? The light, sweet chocolate

or the dark, bitter kind?"

The conversation became general.

They spoke of cherry centers,

of almonds and Brazil nuts.

Losing their inhibitions

they interrupted one another.

For people may not know what they think

about politics in the Balkans,

or the vexed question of men and women,

but everyone has a definite opinion

about the flavour of shredded coconut.

Finally someone spoke of chocolates filled with liqueur,

and everyone, even the author of Uncle Vanya,

was at a loss for words.

As they were leaving he stood by the door

and took their hands.

In the coach returning to Petersburg

they agreed that it had been a most

unusual conversation.

On another occasion (recounted in V.S. Pritchett's Chekhov: A Spirit Set Free), he 'interrupted a wrangling discussion on Marxism with the eccentric suggestion: "Everyone should visit a stud farm. It is very interesting."'

'In a small way, rather remarkable...'

A couple of weeks ago, it was Philip Larkin's centenary – and back in April Kingsley Amis's – and today comes the sesquicentenary of Max Beerbohm, born in Kensington on this day in 1872. His father was a Lithuanian-born grain merchant, his mother the sister of his father's first wife, and it was long surmised that Beerbohm must have Jewish blood (Ezra Pound refers to this, in typically charming philosemitic manner, in 'Hugh Selwyn Mauberley') – but, having looked into the matter, Max told a biographer: 'I should be delighted to know that we Beerbohms have that very admirable and engaging thing, Jewish blood. But there seems no reason for supposing that we have. Our family records go back as far as 1668, and there is nothing in them compatible with Judaism.' He also said: 'That my talent is rather like Jewish talent I admit readily... But, being in fact a Gentile, I am, in a small way, rather remarkable, and wish to remain so.'

The young Max received his early education at a day school run by a Mr Wilkinson, who gave him the only drawing lessons he ever had, and 'gave me my love of Latin and thereby enabled me to write English'. After Charterhouse it was Oxford, where he got to know, among many others, Oscar Wilde and William Rothenstein, who introduced him to Aubrey Beardsley and the Yellow Book circle. He was soon launched, too, as a writer, caricaturist and dandy. 'I was a modest, good-humoured boy,' he recalled. 'It was Oxford that made me insufferable.' In reality, he was the least insufferable of writers – a breed not known for their conspicuous sufferability. Indeed he is one of the few writers with whom I would, I think, have been happy to spend some time (who are the others? Keats, Chekhov, Beckett, Fernando Pessoa, Dr Johnson if I was feeling strong enough, Oscar Wilde ditto). Talking of Oscar, to mark this anniversary I'm going to link back to something I wrote some years ago about one of Beerbohm's lesser known but very remarkable creations, 'A Peep into the Past'. Here's the link...

(The portrait of the young Max above is by his friend, the Dieppe-based painter Jacques-Emile Blanche.)

Monday, 22 August 2022

From Duns to Dunce

You live and learn. Dipping last night into that fine gallimaufry of odds and ends, The Frank Muir Book: An Irreverent Companion to Social History, I discovered that the word 'dunce', denoting a slow-witted person, derives from the name of the great medieval philosopher-theologian Duns Scotus. He it was who developed such ideas as the univocity of being, the formal distinction and, best of all, haecceity (thisness) – not the kind of things you'd expect the average dunce to come up with. However, such was their distaste for the medieval schoolmen that the rising humanists and reformers used the name of one of their number, the unfortunate Duns, as a byword for imbecility. Duns became 'dunce', a word that was to become all too well known to generation after generation of unfortunate schoolchildren who were forced to stand in a corner of the schoolroom, often wearing the conical 'dunce hat'. This can hardly have improved their educational prospects.

Muir quotes Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (the original 1870 edition by the sound of it) to tell the story of how Duns became 'dunce':

'DUNCE. A dolt; a stupid person. The Word is taken from Duns Scotus (c.1265-1308), so called from his birthplace, Dunse, in Scotland, the learned schoolman. His followers were called Dunsers or Scotists. Tyndal [William Tyndale] says, when they saw that their hair-splitting divinity was giving way to modern theology, 'the old barking curs raged in every pulpit' against the classics and new notions, so that the name indicated an opponent to progress, to learning, and hence a dunce.'

(By the way, apropos 'hair-splitting divinity', the medieval schoolmen never did argue over how many angels could dance on the head of a pin, though the calumny is still widely believed.)

Duns Scotus – 'who of all men most sways my spirits to peace' – was a favourite of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and the subject of one of his sonnets. The opening lines, with their evocation of a still semi-rural medieval Oxford, are rather lovely, I think...

Duns Scotus's Oxford

Saturday, 20 August 2022

'It was always weather'

In Lichfield, that 'city of philosophers', the talk often turns to weather. Indeed, the weather might well be the number one topic of conversation, and lately there has been plenty to talk about, what with the heatwave and the dramatic downpours that broke it. I have no problem with this, as I find weather as interesting a topic as any, and one that is far more than merely the small change of everyday conversation. In the end there is little that is more basic to our life on earth than the weather – as it has a habit of reminding us whenever it gets extreme, and if we happen to find ourselves out of doors, in the thick of it, on a day of heavy weather. It affects our mood, our emotions, our physical health, and indeed our brain function, as that recent heatwave reminded us. Because of its potentially devastating, famine-inducing impact on farming and food production, weather was surely a central preoccupation of every agrarian society, and is still of huge importance to farmers, even in countries with the most highly developed agriculture. And of course this preoccupation, this lively fear of adverse weather, fed into early forms of religion – and more evolved ones: there were impassioned prayers for rain and for fair weather in the first Book of Common Prayer, and even the 1928 edition contains a prayer for 'seasonable' weather ('Send us, we beseech thee, such seasonable weather that we may receive the fruits of the earth to our comfort, and thy honour.'). Here is R.S. Thomas's take on it all...

Meteorological

It was always weather.

The reason for our being

was to record it, telling it

how it was hot, cold, wet

to the pointlessness of saturation.

It was a disposition

of the impersonal, an expression

on what could have been

blank space. It repeated itself

in a way we were never tired

of listening to. 'Do that again,'

we implored it on the morrow

of a fine day. When it was grey

you could have described it

as sullen. On sparkling mornings

it flashed us smile after smile so

we became familiar with it.

It breathed then into our very being

refrigerating us. To curse it

was to have it regard us

out of the mildest of skies,

fondling us with the wind's

tapering fingers. They say

it was like this before

our arrival. How could it

have been without us

to convince it? What, when we

have gone, will become

of it, endlessly occurring

over our vocabulary's Sahara?

Thursday, 18 August 2022

'I can't recall how I spent my time before Google...'

It was ten years ago today that the sweet-voiced singer Scott McKenzie died, at the age of 73. He was never a natural fit with the biz we call show, and not long after the blazing success of the hippie anthem San Francisco, he retreated from the spotlight and largely retired from the business in favour of living a life. Not long before his death, he described himself thus: 'Reclusive septuagenarian. I live with a 15 year old cat named Spider in Silverlake, which is in Los Angeles. I spend lots of time on the internet, mainly researching all sorts of things – I can't recall how I spent my time before Google. I was a professional singer for years, had a 1967 hit called "If You're Going to San Francisco, Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair". I sang at The Monterey Pop Festival. I've lived In New York City; Laurel Canyon; San Francisco; Virginia Beach. I cherish my friends, many of whom have passed on. This trend shows no signs of abating.'

A short post I wrote about McKenzie (born Philip Wallach Blondheim III, fact fans) on his 70th birthday scored more hits than any other post on this blog. I've no idea why, but it's worth trying again – here's the link...

Monday, 15 August 2022

Marriage and a Postcard

Now I'm no longer paid to watch the stuff, I seldom look at anything new on television. Rashly tuning in to the new BBC1 drama Marriage last night reminded me how little I'm missing. Lord, it was dreadful, about as exciting as watching paint dry, and far less good for the soul. The dialogue, what there was of it, was often inaudible (as is the fashion these days), and vast oceans of time passed while nothing happened apart from someone tackling a sachet of tomato ketchup or mayonnaise with their teeth, or walking to or from a car, getting into or out of it, joining a queue, standing about, zzzz... And it was as mystifying as it was dreary – as is also the fashion, as if forcing us to work out what is going on somehow makes whatever it is intrinsically more interesting (it doesn't and it ain't). After about three quarters of an hour, a potentially interesting storyline finally hove into view when we met a young woman who we are asked to believe is the adopted daughter of the couple whose Marriage this is, though there was no chemistry whatsoever among the three of them. The daughter's new boyfriend is apparently a coercive controller, but I shan't be watching to find out how that, or anything else in this dreary drama, plays out. As usual, good actors (Nicola Walker, Sean Bean) were wasted in this, let down by a woefully inadequate script and a lifeless production.

As it happened, the night before I had caught Clive James: Postcard from Paris, a film he made in 1989. It was a reminder of how much fresher and faster and smarter this kind of thinking man's travelogue was in those days. No sooner had he arrived in Paris than Clive was being driven around the streets of Paris at suicidal speeds by Françoise Sagan, no less. It was edge-of-seat stuff, and it was hard to work out how on earth they managed to film it, let alone how it got past the lawyers. Things quietened down a bit after that, but there were none of the longueurs that punctuate similar films today, and none of the silly stunts that producers feel obliged to inflict on presenters (see Michael Palin, Portillo et al.). And of course, Clive James being Clive James, the script, if sometimes glib, was intelligent, insightful and funny. There'll never be another – and if there was, he wouldn't be allowed to make films like Postcard from Paris.

Saturday, 13 August 2022

Indulging a Maggot

Talking of Tristram Shandy, yesterday Patrick Kurp quoted a bravura passage from that curious masterpiece, in which Sterne digresses on 'hobby-horses', a favourite subject of his and a major theme of the novel –

'Nay, if you come to that, Sir, have not the wisest men of all ages, not excepting Solomon himself, – have they not had their HOBBY-HORSES; – their running horses, – their coins and their cockle-shells, their drums and their trumpets, their fiddles, their pallets, – their maggots and their butterflies? –'

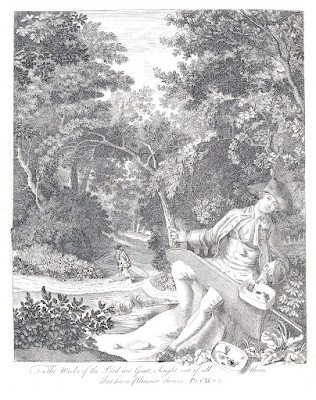

'Their maggots and their butterflies' was the phrase that caught my eye. 'Maggots' is here used in its generic sense, covering all kinds of larvae, not just those of house flies and bluebottles. Sterne will be thinking of the caterpillars which, after pupating, become butterflies. Both 'maggots' and 'butterflies' have connotations of the whimsical or frivolous (very much Sterne's own line), a maggot being in one early usage 'a whimsical fancy; a crotchet' (OED), and a butterfly 'a vain, gaudily attired person; a giddy trifler' (probably what Lear means when he speaks of laughing at 'gilded butterflies'). However, Sterne is surely alluding here to the enthusiasts then known as Aurelians, whose hobby-horse drove them to take a perhaps mildly obsessive interest in butterflies and indeed caterpillars. In Sterne's time, lavish and beautiful books of hand-coloured prints showing the life cycle of butterflies were in vogue. He might well have seen Benjamin Wilkes's English Moths and Butterflies (published 1749), and Moses Harris's glorious The Aurelian (frontispiece below) had been published the year before the final volume of Tristram Shandy. Isn't there something a little Sternean about the figure in the foreground (probably a self-portrait of Harris)? Or am I indulging a maggot?

Butterflies are, of course, my own hobby-horse, or one of them – one that I am riding rather hard at the moment as I wrestle with what might or might not become a book on the subject. It is a harmless enough pursuit: 'So long as a man rides his HOBBY-HORSE peaceably and quietly along the King's highway, and neither compels you or me to get up behind him, – pray, Sir, what have either you or I to do with it?' Quite.

Thursday, 11 August 2022

Sternean Evolution?

'To New Guinea I took an old edition of "Tristram Shandy" which I read about three times. It is an annoying & you will perhaps say a very gross book, but there are passages in it that have never been surpassed while the character of Uncle Toby has certainly never been equalled, except perhaps by that of Don Quixote...'

Who is writing here? The clue is in the mention of New Guinea: it is the much travelled naturalist and collector Alfred Russel Wallace, he who independently of Darwin came up with the theory of evolution by natural selection. Wallace is writing from Bacan in the Moluccas to his friend George Silk in London. The signature at the end of the letter is botched – 'PS A big spider fell close to my hand in the middle of my signature, which accounts for the hitch.'

The letter was written in the same year in which Wallace conceived his theory of natural selection – a theory that came to him in a flash when he combined the insights of a range of biologists (as we would now call them ) with Malthus's ideas on population growth. He was in the throes of the Genghis ague – malaria, as we now call it – and thrashing about on a sweat-soaked bed, his head splitting, his body racked with fever chills, when he had his light-bulb moment. Did his recent, repeated reading of "Tristram Shandy" play any part in its conception? The obvious answer is No, but there may be a Ph.D. thesis in it for someone...

I've always had a bit of a soft spot for Russell, the 'nearly man' of evolutionary theory, the dauntless, prodigiously hard-working self-made commercial collector among all those gentlemen scientists (Darwin, Lyell, etc.), and I'm glad his star has risen again in recent years, thanks in part to the advocacy of that man of many parts Mr Bill Bailey. Wallace wrote a quite extraordinary account of an encounter with a butterfly – the one that came to be named Wallace's Golden Birdwing: 'The beauty and brilliancy of this insect are indescribable, and none but a naturalist can understand the intense excitement I experienced when I at length captured it. On taking it out of my net and opening the glorious wings, my heart began to beat violently, the blood rushed to my head, and I felt much more like fainting than I have done when in apprehension of immediate death. I had a headache the rest of the day, so great was the excitement produced by what will appear to most people a very inadequate cause.' Oh, I don't know...

Wednesday, 10 August 2022

On the Hill

From the train this morning, the dip slope of Box Hill looked more like desert than grassland – as did most of the usually grassy open spaces I saw along the way. This drought is certainly having an impact (though I was pleased to find that the river Mole, though a bit low, is still flowing well, as is the upper Wandle), and it looks as if it will be with us a while yet, along with some pretty fierce heat. Anyway, I wasn't intending to walk up that parched slope. I took a taxi from the station to the famous viewpoint at the top of Box Hill (as featured, I believe, in Emma), and from there I walked down to one of my regular August haunts, where I hoped to find the Adonis Blue and Silver-Spotted Skipper, two of our loveliest, and latest-flying, butterflies.

My first impression was of a drought-struck and desolate landscape, with barely a flower to be seen, and nothing flying but a few doughty Gatekeepers and Meadow Browns. However, as so often, when I had slowed my pace, often to a standstill, and got my attention focused, I discovered that there was green growth to be found, there were flowers – though nothing like as many as usual – and, praise be, there were butterflies. Soon I was seeing Chalkhill Blues everywhere, then my first Silver-Spotted Skipper – the first of many, as it turned out. The Adonis Blue was harder to find, but after a while, closing in on a slight fluttering I'd noticed in a tussock, I discovered that I had found not one, but two – a male and a female taking a breather in the midst of an epic courtship chase: they were off again as soon as I'd seen them, and were chasing around at speed for the rest of the time I was there. I saw a few more Adonises too, and another one on my way back down the hill, by way of the gentler and less exposed areas of the dip slope. As I also saw a couple more Silver-Spotted Skippers, in a place where I'd never seen them before, I returned home well satisfied: I had seen the heavenly blue of the male Adonis's wings, and more than once enjoyed the Silver-Spotted Skipper's beautiful green-and-silver underwings. My butterfly summer is complete (all bar the elusive Brown Hairstreak). What more could an aurelian ask?

Tuesday, 9 August 2022

The Big One

The heatwave continues here in southern England, and spreading across much of the country, maybe even to Hull, to Coventry... How would the 'summer-born and summer-loving' Philip Larkin be enjoying it? 'Enjoying it'? It's Larkin we're talking about here, and he was too much his mother's son to simply enjoy it...

Mother, Summer, I

Holds up each summer day and shakes

It out suspiciously, lest swarms

Of grape-dark clouds are lurking there;

But when the August weather breaks

And rains begin, and brittle frost

Sharpens the bird-abandoned air,

Her worried summer look is lost,

And I her son, though summer-born

And summer-loving, none the less

Am easier when the leaves are gone.

Too often summer days appear

Emblems of perfect happiness

I can't confront: I must await

A time less bold, less rich, less clear:

An autumn more appropriate.

I have written so often here on Larkin, and posted so many of his poems (try a search), that he has become a kind of tutelary deity of this blog. What can I add today? Only this perhaps – that if you haven't read his novel, A Girl in Winter, you really should. It is a revelation.

Saturday, 6 August 2022

Justice's Farewell

It was on this day in 2004 that Donald Justice, one of America's finest poets, died. As David Orr wrote of him, 'sometimes his poems weren't just good; they were great. They were great in the way that Elizabeth Bishop's poems were great, or Thom Gunn's or Philip Larkin's. They were great in the way that tells us what poetry used to be, and is, and will be.' Quite so.

Here is one of the last poems Justice wrote, and one of those that is indeed great. In painterly terms it is a triptych. The first panel is a Crucifixion scene, bathed in the even light of divine love (charity). The second is a scene from the Orpheus legend, expressing the pain of love and parting. And in the third, a direct paraphrase from Chekhov's Uncle Vanya, Sonya Alexandrovna paints a wishful vision of the life to come. The three six-line sections of this poem (with their ingenious whole-word rhyming) add up to something far larger than its parts – a poised and poignant farewell to the world.

1

There is a gold light in certain old paintings

That represents a diffusion of sunlight.

It is like happiness, when we are happy.

It comes from everywhere and nowhere at once, this light,

And the poor soldiers sprawled at the foot of the cross

Share in its charity equally with the cross.

2

Orpheus hesitated beside the black river.

With so much to look forward to he looked back.

We think he sang then, but the song is lost.

At least he had seen once more the beloved back.

I say the song went this way: O prolong

Now the sorrow if that is all there is to prolong.

3

The world is very dusty, uncle. Let us work.

One day the sickness shall pass from the earth for good.

The orchard will bloom; someone will play the guitar.

Our work will be seen as strong and clean and good.

And all that we suffered through having existed

Shall be forgotten as though it had never existed.

Thursday, 4 August 2022

Johnson on the Duvet

I've bought, for a tiny sum, another tiny volume from the Carr's Pocket Books series, published by the Quince Tree Press from J.L. Carr's home in Kettering. This one, titled The Sayings of Chairman Johnson, is a well chosen little anthology of quotations from Samuel Johnson's writings and utterances (including the whole of his famous letter to his dilatory patron, Lord Chesterfield, and some lines from 'The Vanity of Human Wishes'). The collection, 'arranged by Edmund Kirby', is prefaced by a quotation from (Professor) Sir Walter Raleigh: 'The memory of other authors is kept alive by their works. But the memory of Johnson keeps many of his works alive. The old philosopher is still among us in his brown coat with the metal buttons and the shirt which ought to be at wash, blinking, puffing, rolling his head, drumming his fingers, tearing his meat like a tiger, and swallowing his tea in oceans. No human being who has been seventy years in the grave is so well known to us.' True enough, thanks to Boswell's extraordinary feat of sympathetic, indeed loving (and therefore unblinking) biography.

One entry in The Sayings of Chairman Johnson brought me up short. A quotation from The Idler, it reads: 'Promise, large promise, is the soul of an advertisement ... and there are now to be sold for ready money only, some Duvets for bed-coverings, of down, beyond comparison superior to what is called Otter Down: warmer than four or five blankets and lighter than one.'

Duvets? In the mid-eighteenth century? Even two centuries later, duvets were regarded with suspicion as something only foreigners would use; we English were quite content to sleep under woollen blankets. It was Terence Conran who finally popularised the use of duvets in this country, and it was not until the 1970s that they began to become a standard form of bedding.

'Duvet' is of course a French word, meaning down, and Johnson seems to have been the first English writer to use it. There had been at least one attempt to introduce the duvet to England in the seventeenth century, when the diplomat and historian of the Ottoman Empire Sir Paul Rycaut sent his friends a quantity of eider down, with instructions on how to turn it into a warm bed covering. He had come across the duvet in Hamburg and felt sure it would be a boon in the English winter. However, the blanket-loving English wanted none of it. By the sound of Johnson's remarks on advertising, it would seem another campaign to introduce the duvet was under way half a century after Rycaut's efforts. If so, it was again doomed to failure. Only Terence Conran, it seems, could make this foreign innovation palatable to the English.

Monday, 1 August 2022

'The shell of balance rolls in seas of thought...'

The great naturalist Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck, better known simply as Lamarck, was born on this day in 1744. He is remembered chiefly for his evolutionary ideas, notably the inheritance of acquired characteristics. It's an idea that seemed to have been rendered irrelevant by the development of genetics and the discovery of DNA as an apparently sufficient explanation for all heredity. Then along came transgenerational epigenetics, in which heritable characteristics occur in response to the environment without any alteration of DNA. At least I think that's how it works...

Here is a poetical response – 'Lamarck Elaborated' by Richard Wilbur, in which he takes the Lamarckian idea that 'the environment creates the organ' and runs with it...

"The environment creates the organ"

The Greeks were wrong who said our eyes have rays;

Not from these sockets or these sparkling poles

Comes the illumination of our days.

It was the sun that bored these two blue holes.

It was the song of doves begot the ear

And not the ear that first conceived of sound:

That organ bloomed in vibrant atmosphere,

As music conjured Ilium from the ground.

The yielding water, the repugnant stone,

The poisoned berry and the flaring rose

Attired in sense the tactless finger-bone

And set the taste buds and inspired the nose.

Out of our vivid ambiance came unsought

All sense but that most formidably dim.

The shell of balance rolls in seas of thought.

It was the mind that taught the head to swim.

Newtonian numbers set to cosmic lyres

Whelmed us in whirling worlds we could not know,

And by the imagined floods of our desires

The voice of Sirens gave us vertigo.