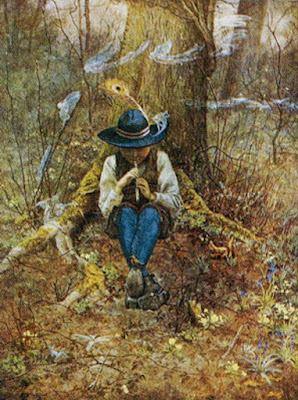

This painting – The Piper of Dreams by Estella Canziani – was the subject, or one of the subjects, of a fascinating talk on Radio 3 last night (in the often rewarding slot labelled The Essay). I had never heard of it or knowingly seen it before, but this was a picture that made a huge impact in its day – its day being 1915, when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy and created a sensation. Reproduced in various formats and in huge numbers by the Medici Society, it found its way to many parts of the world, eclipsing even Holman Hunt's The Light of the World in popularity, and, in particular, it gave solace to soldiers in the trenches and to their families. It is hard, now, to see quite why, but presumably it had something to do with the peaceful English woodland setting, the otherworldly, magical feel of the image – and those fairies that are flying around the piper and cavorting on the forest floor. This other world, on the edge of material reality and outside of time, could hardly have been further from the grim realities of life in the trenches, and perhaps there was some kind of consolation in those fairy presences.

The vogue for fairy painting, having taken off in the mid-Victorian period with the likes of Richard 'Dicky' Doyle and John Anster Fitzgerald ('Fairy Fitzgerald'), had never really gone away, and fairies were very much, as it were, in the air in the Great War period: the famous Cottingley fairy photos, fakes that took in many people, including Conan (nephew of Dicky) Doyle, were taken in 1917, the same year as Liza Lehmann's much-parodied song 'There Are Fairies at the Bottom of Our Garden'. Not long after the war, the Flower Fairies books of Cecily Mary Barker began to be published with great (and lasting) success. But The Piper of Dreams also relates to another curious obsession of the time – with the piping faun of the forest, Pan, who turns up in the writings of Oscar Wilde, Arthur Machen, Saki, Eleanor Farjeon and a host of others, including even E.M. Forster (The Story of a Panic, 1911). His most memorable appearance, perhaps, is in the weirdly incongruous 'Piper at the Gates of Dawn' interlude in The Wind in the Willows. What is it with us Brits? Supposedly hard-headed empiricists, we seem always to have been addicted to fantasy and enchantment, to imagined pasts that never existed, to myth and mystification, to talking animals and creatures of magic – hence, I suppose, our world-conquering fantasy literature, from Lewis Carroll to J.K. Rowling, by way of Narnia and the Riverbank, Middle Earth and the world of Beatrix Potter. And those are just the highlights...

As for Estella Canziani, fairies were by no means her only line: she painted portraits and landscapes, and was an interior decorator, travel writer and folklorist, especially of northern Italy. She lived all her life (1887-1964) at the very illustrious address of 3 Palace Green, in the grounds of Kensington Palace.

Thursday, 11 May 2023

The Piper of Dreams

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

S.J. Perelman, in one of his Cloudland Revisited pieces, quotes Max Beerbohm from the story "Hilary Maltby and Stephen Braxton", collected in Seven Men: "From the time of Nathaniel Hawthorne to the outbreak of the War, current literature did not suffer from any lack of fauns." I do think that the British suffered from this more than Americans, though Perelman was writing about an American novel, The Bride of the Centaur, and of course Hawthorne got in early with The Marble Faun.

ReplyDeleteI don't know why fauns etc. so appealed to the British. Every nation has its quirks, and though I understand American quirks very well, I can only guess at other peoples'.

Thanks for that – a great quote. Maybe the French have a thing too? L'Après-Midi d'un Faune and all that...

ReplyDelete